cvalue13

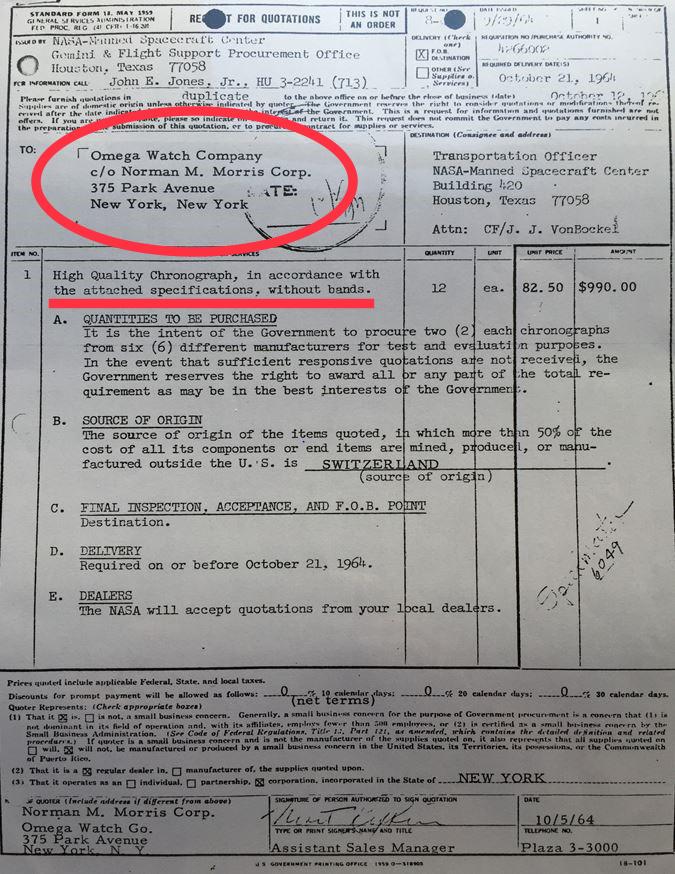

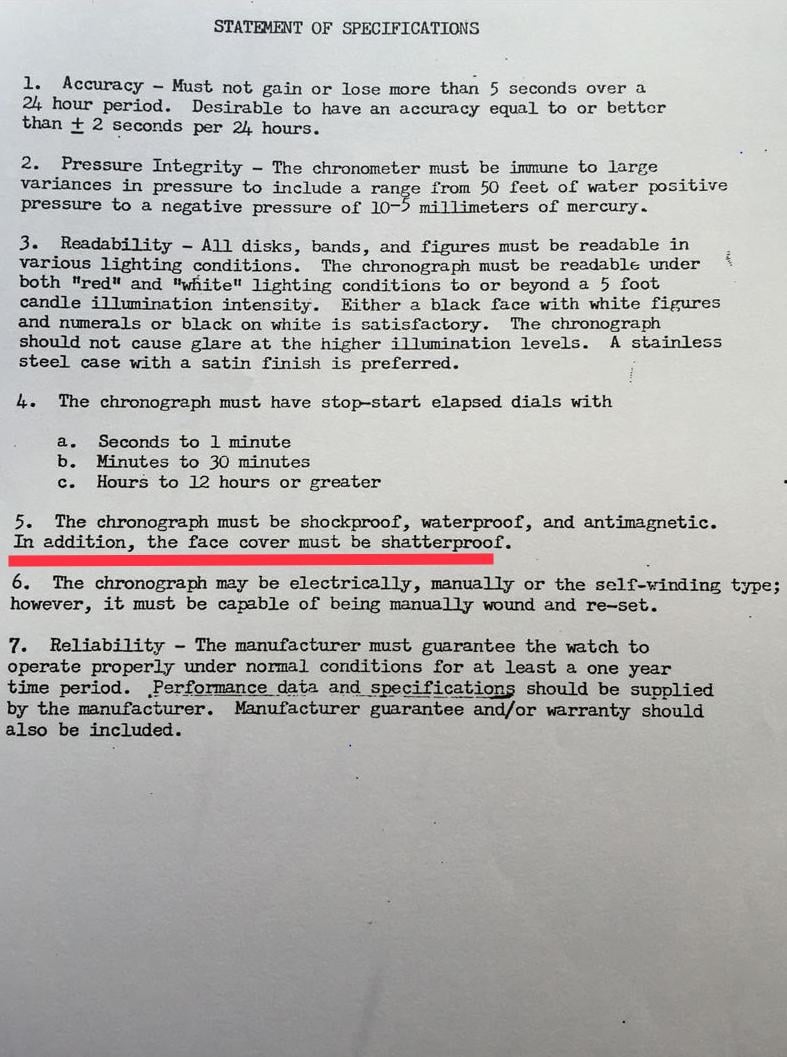

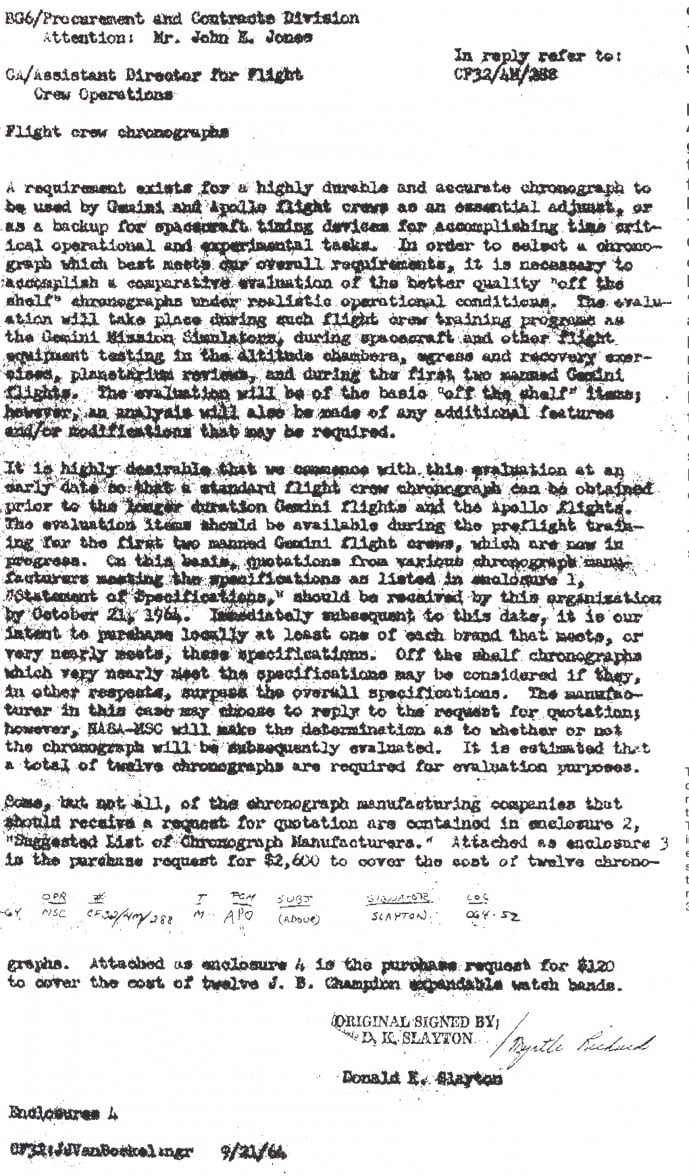

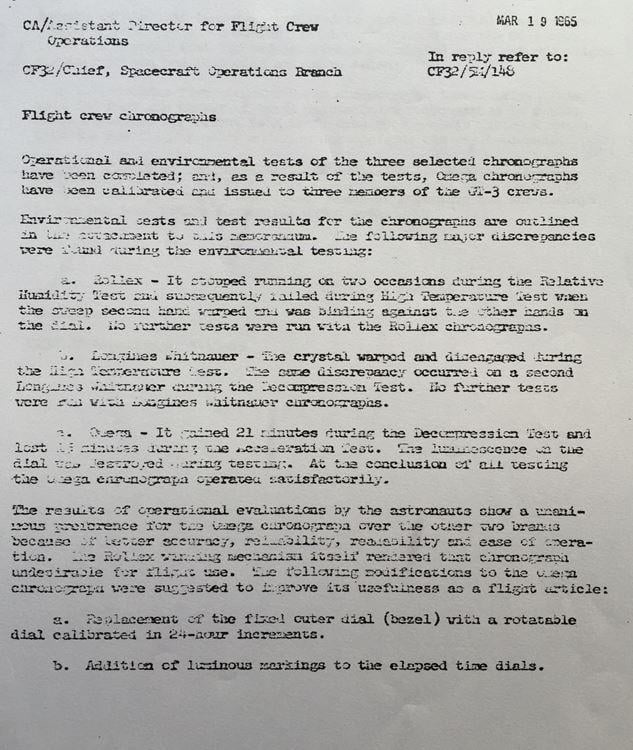

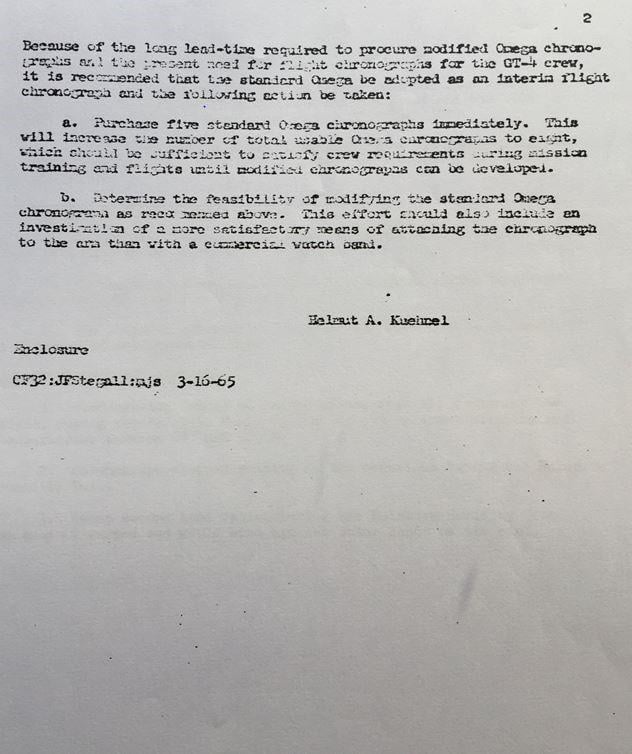

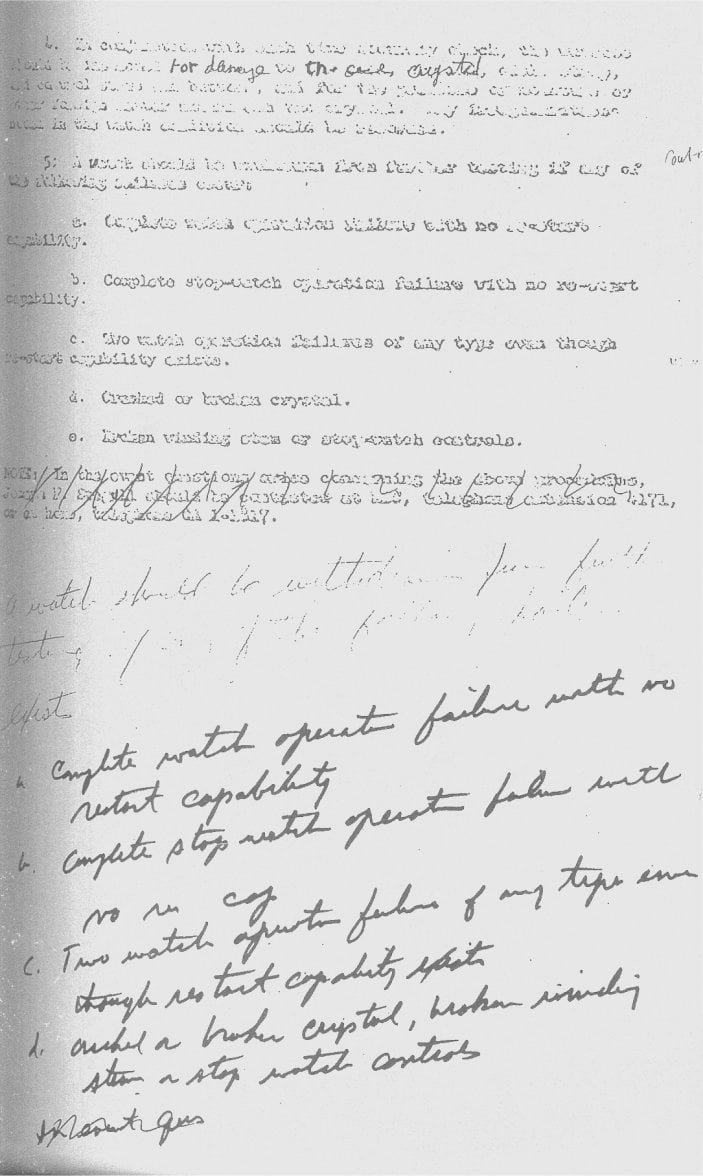

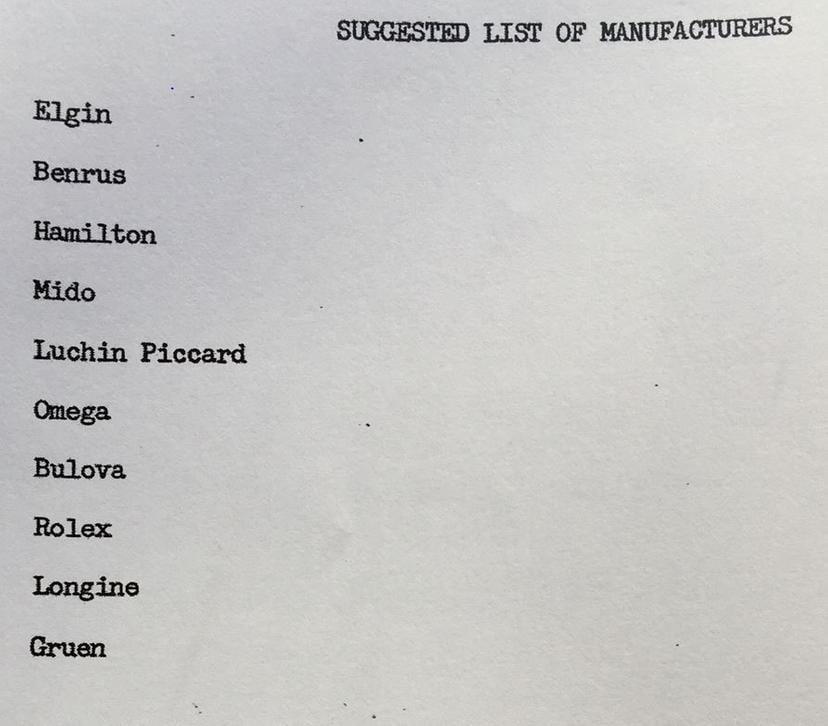

·See at bottom an extract from the 1964 memo specifying that the chronograph crystal be shatterproof, as well as the Omega invoice to NASA responsive to the statement of specifications.

The same engineer, Regan, responsible for chronograph selection, was responsible also for camera selection.

I don’t think anyone is saying they didn’t have glass instruments or articles on board. They did, and still do to this day. The question instead is relevance of that fact.

The reason I posted the more contemporary white paper of NASA and ISS safety regulations regarding frangible materials was to show the sort of cost-benefit analysis going into the allowances for frangible materials. Glass is avoided where practical, and where unavoidable (eg optical glass, computer and TV monitors, research equipment, etc.), then additional storage, containment, and usage precautions are implemented.

Your showing of the Armstrong optic glass (cameras) is a great example of this: the ISS safety regs have an entire section specifically dealing with procedures around optic glass; unlike a watch crystal, optical glass is a materials selection instance where glass is necessary, and so there are additional safety reqs and procedures around the existence of optical glass in the vehicle.

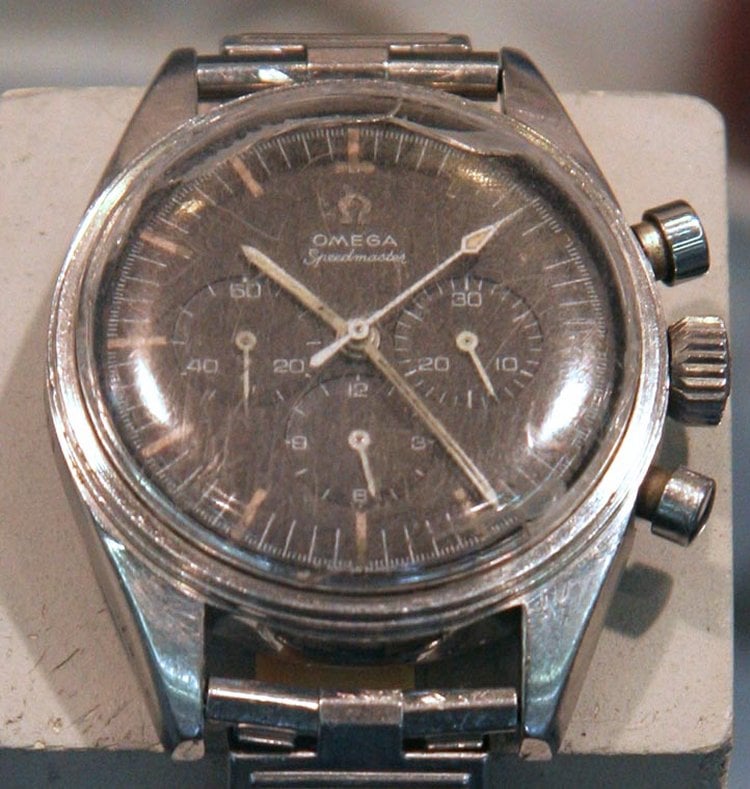

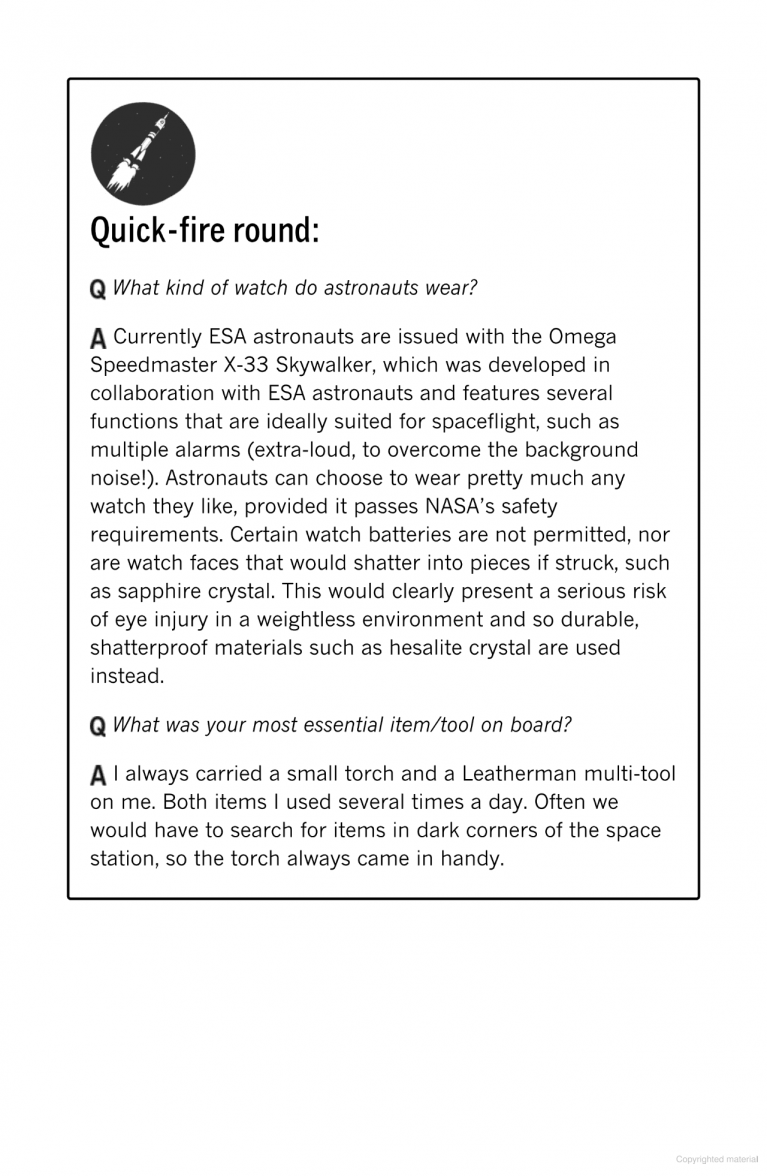

Point being: it seems uncontroversially true that there was glass on board then and now, and at the same time that seems irrelevant to any conclusion regarding the requirement for a “shatterproof” crystal on the chronograph selected (which requirement was explicitly in the period correct statement of specs). Unlike accepting the risk of optic glass on board, there was no sufficient reason to not require a shatterproof crystal.

Which is why NASA specified the need for a shatterproof crystal in the 1964 memorandum that went out to manufacturers:

this has also got me wondering if they did anything special for the cameras

The same engineer, Regan, responsible for chronograph selection, was responsible also for camera selection.

Some of the items found after Neil Armstrong died also look like they had glass elements ..

I don’t think anyone is saying they didn’t have glass instruments or articles on board. They did, and still do to this day. The question instead is relevance of that fact.

The reason I posted the more contemporary white paper of NASA and ISS safety regulations regarding frangible materials was to show the sort of cost-benefit analysis going into the allowances for frangible materials. Glass is avoided where practical, and where unavoidable (eg optical glass, computer and TV monitors, research equipment, etc.), then additional storage, containment, and usage precautions are implemented.

Your showing of the Armstrong optic glass (cameras) is a great example of this: the ISS safety regs have an entire section specifically dealing with procedures around optic glass; unlike a watch crystal, optical glass is a materials selection instance where glass is necessary, and so there are additional safety reqs and procedures around the existence of optical glass in the vehicle.

Point being: it seems uncontroversially true that there was glass on board then and now, and at the same time that seems irrelevant to any conclusion regarding the requirement for a “shatterproof” crystal on the chronograph selected (which requirement was explicitly in the period correct statement of specs). Unlike accepting the risk of optic glass on board, there was no sufficient reason to not require a shatterproof crystal.

Which is why NASA specified the need for a shatterproof crystal in the 1964 memorandum that went out to manufacturers: