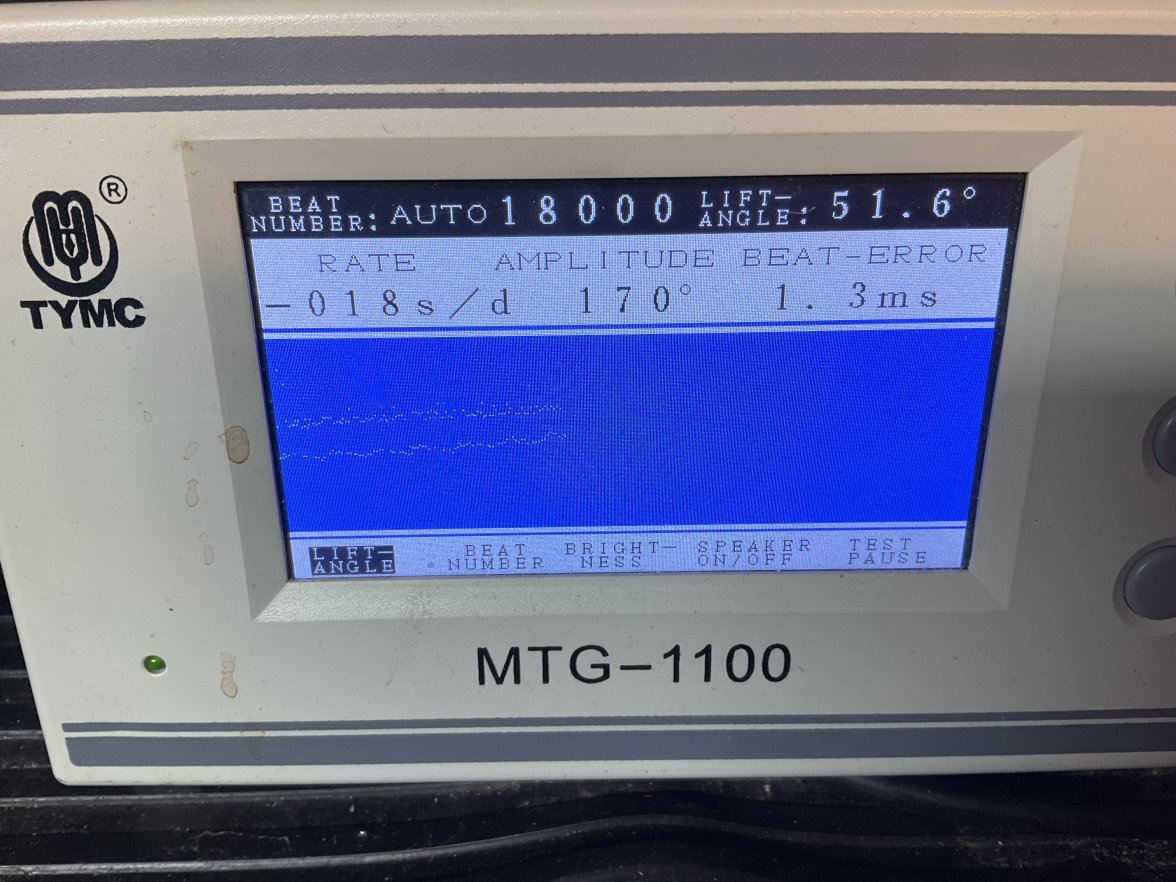

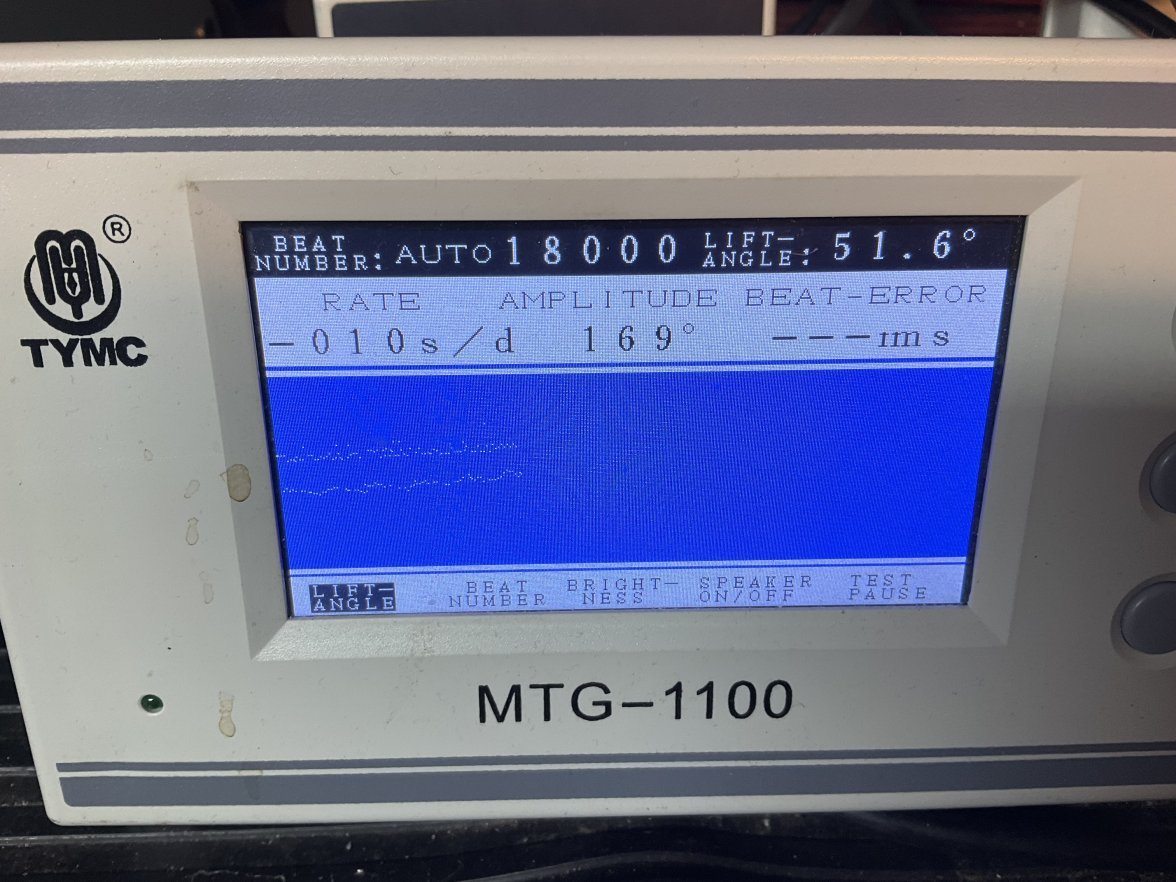

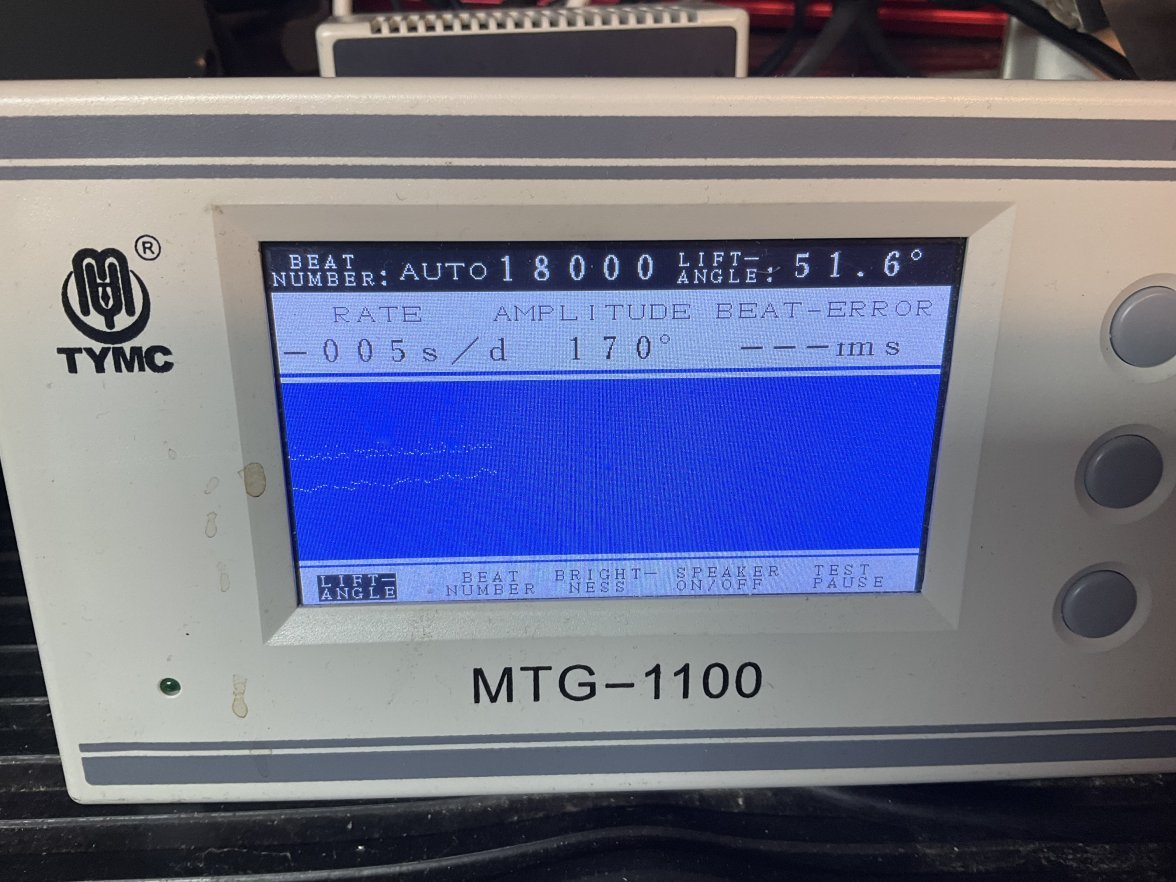

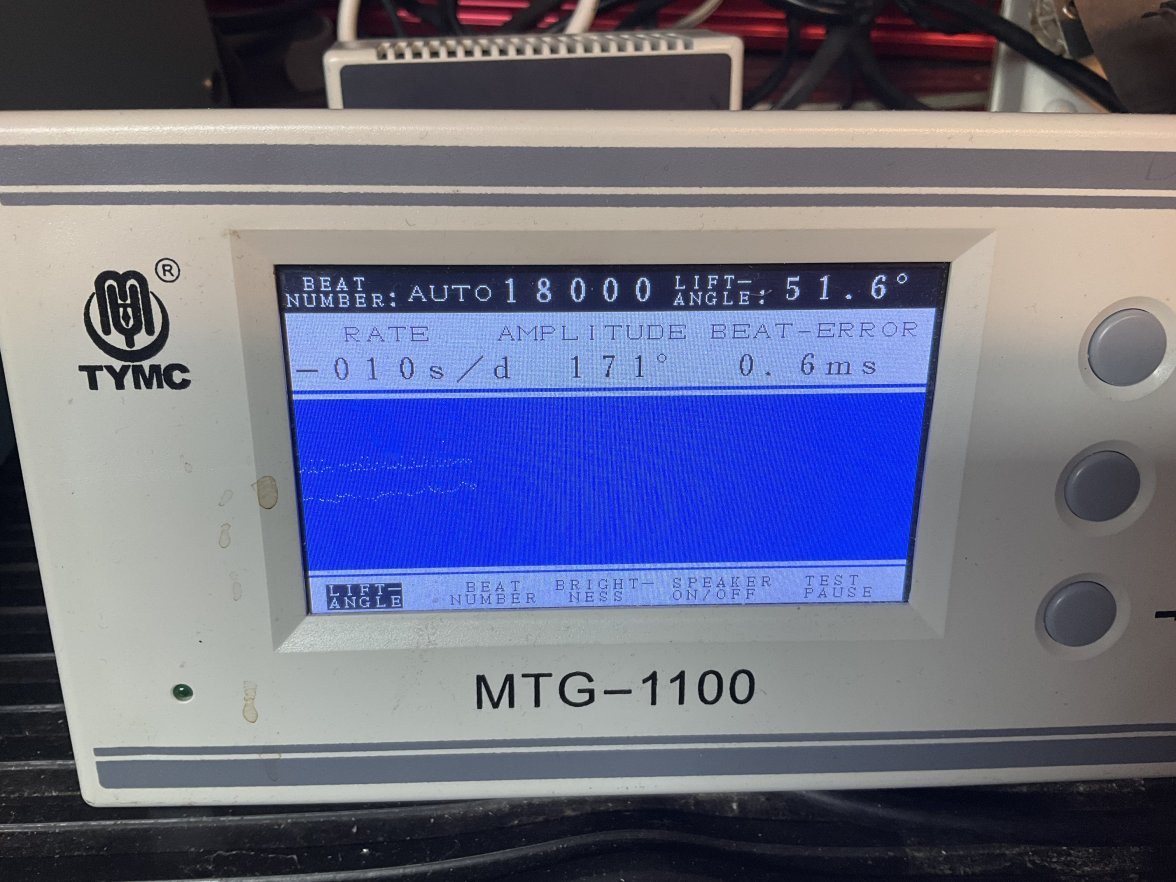

I’ve had watches come in that we’re clearly in need of service, but in my initial timing tests had a Delta over 100 seconds, but they averaged out to near zero, so it happens. If you wore the watch so that it spent time on your wrist in exactly the same way it did on the timing machine, it would run great. But of course that’s pretty much impossible. That’s why reducing the Delta is so important to good timekeeping.

Regulating is fine tuning the final rate. It’s normally done on the timing machine, and then verified after the watch is assembled. Personally I perform static tests for 24 hours in each position, plus another test on a test winder (very different machine from a consumer winder). From there I adjust the average rate to where I want it to be, generally slightly positive (people usually want a few seconds per day positive, but not even 1 second a day negative).

Regulating is the easy part, and the last thing done.

Adjusting, which is done to reduce the Delta is the hard part. That’s all done on a timing machine, and causes for variation depend partly on the design of the movement. Things such as the balance being free sprung or using regulating pins will change the potential causes of positional errors.

I’ll be leaving out the issues that would be caused by wear (such as worn balance pivots for example), or other more fundamental repair issues, because these things all need to be repaired before final adjustment even begins. So these below are pure adjustment issues.

By no means is this exhaustive, especially since it’s New Year’s Eve and I’m well under way celebrating...but here are some possible causes:

Balance spring not concentric (includes coils not being evenly spaced).

Balance spring out of flat (raised up on one side, coned, etc.).

Balance spring not centred in the regulating pins.

Regulating pins not spaced correctly.

Regulating pins not parallel.

Poise errors on balance.

These things are not diagnosed completely with the timing machine, as it requires detailed inspection under magnification to determine what the problem is specifically. I listed the poise error last, because you only start adjusting that once you know everything else is 100% perfect.

This isn’t some magical thing that cannot be explained, even though it seems that’s what some people want you to believe. Honestly some of the answers given in this thread border on nonsense. Anyway, it’s pretty basic stuff for any watchmaker, but would be considered advanced work for an amateur to tackle these things.