Not all things in Australia want to kill you..........

Foo2rama

··Nowhere near as grumpy as he used to be...rob#1

·This guy seems friendly enough...

https://www.cairnspost.com.au/news/...q/news-story/85593251921992fc03c5fcf475e20009

https://www.cairnspost.com.au/news/...q/news-story/85593251921992fc03c5fcf475e20009

STANDY

··schizophrenic pizza orderer and watch collectorBaby dinosaur near the walking path between Manly & Shelly Beach in Sydney today.

It's a baby because it's only 4 times the length of the kid's forearm. 😉

PS: they're actually Australian Water Dragons, grow to about a metre, and won't kill you. If you visit Sydney a trip to Manly is definitely time well spent and you might see some of these friendly locals. 😀

Notice he said walking path between the beaches. Aussies don’t go the beach

Stonefish

Although it looks like a gross swimming rock, it's actually a super poisonous fish covered in needle-like spines. What a twist! Rather than actually swimming it stays stationary on rocks to camouflage itself, and is sometimes encountered by unfortunate swimmers. Here's a quote from the victim of one such Stonefishing: "Imagine having each knuckle, then wrist, elbow, and shoulder being hit with a sledgehammer over the course of about an hour. Then imagine taking a real kicking to both kidneys for about 45min." If you're thinking, "Phew, good thing I read this article and will never, ever swim in Australian waters", Stonefish can survive on land for up to 24hrs. Perhaps it's best to go to New Zealand after all...

Cone snails

This seemingly wussy-looking mollusk is the Cone snail, and it sucks. Here's why; it's evolved an utterly non-rad radular tooth that can be launched out of its mouth like a harpoon at unsuspecting prey (and your foot). After that, the snarpoon will pump you full of neurotoxins, ensuring that you puke and crap yourself until the poison has successfully filtered through your bloodstream.

Matty01

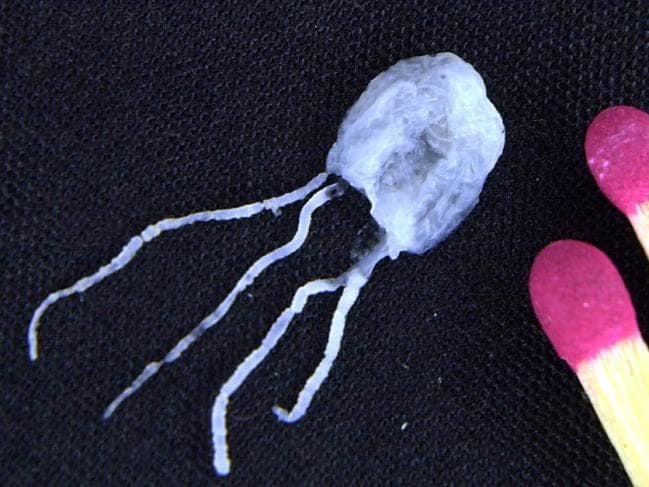

·Irukandji

Irukandji syndrome is produced by a small amount of venom and induces excruciating muscle cramps in the arms and legs, severe pain in the back and kidneys, a burning sensation of the skin and face, headaches, nausea, restlessness, sweating, vomiting, an increase in heart rate and blood pressure, and psychological phenomena such as the feeling of impending doom.[19]The syndrome is in part caused by release of catecholamines.[12] The venom contains a sodium channel modulator.[12]

The sting is moderately irritating; the severe syndrome is delayed for 5–120 minutes (30 minutes on average). The symptoms last from hours to weeks, and victims usually require hospitalisation. Contrary to belief, researchers from James Cook University and Cairns hospital in far north Queensland have found that vinegar promotes the discharge of jellyfish venom. "You can increase the venom load in your victim by 50 per cent," says Associate Professor Jamie Seymour from the Australian Institute of Tropical Health and Medicine at the university. "That's a big amount, and that's enough to make the difference, we think, between someone surviving and somebody dying."[20] However, other research indicates that while vinegar may increase the discharge from triggered stingers, it also prevents untriggered stingers from discharging; since the majority of stingers do not trigger immediately, the Australian Resuscitation Council continues to recommend using vinegar.[21]

Treatment is symptomatic, with antihistamines and anti-hypertensive drugs used to control inflammation and hypertension; intravenous opioids, such as morphine and fentanyl, are used to control the pain.[20] Magnesium sulfate has been used to reduce pain and hypertension in Irukandji syndrome,[22] although it has had no effect in other cases.[23]

Irukandji jellyfish are usually found near the coast, attracted by the warmer water, but blooms have been seen as far as five kilometres offshore. When properly treated, a single sting is normally not fatal, but two people in Australia are believed to have died from Irukandji stings in 2002 during a rash of incidents on Australia's northern coast attributed to these jellyfish[3][24][25][26]—greatly increasing public awareness of Irukandji syndrome. It is unknown how many other deaths from Irukandji syndrome have been wrongly attributed to other causes. It is also unknown which jellyfish species can cause Irukandji syndrome apart from Carukia barnesi and Malo kingi.[27]

Irukandji syndrome is produced by a small amount of venom and induces excruciating muscle cramps in the arms and legs, severe pain in the back and kidneys, a burning sensation of the skin and face, headaches, nausea, restlessness, sweating, vomiting, an increase in heart rate and blood pressure, and psychological phenomena such as the feeling of impending doom.[19]The syndrome is in part caused by release of catecholamines.[12] The venom contains a sodium channel modulator.[12]

The sting is moderately irritating; the severe syndrome is delayed for 5–120 minutes (30 minutes on average). The symptoms last from hours to weeks, and victims usually require hospitalisation. Contrary to belief, researchers from James Cook University and Cairns hospital in far north Queensland have found that vinegar promotes the discharge of jellyfish venom. "You can increase the venom load in your victim by 50 per cent," says Associate Professor Jamie Seymour from the Australian Institute of Tropical Health and Medicine at the university. "That's a big amount, and that's enough to make the difference, we think, between someone surviving and somebody dying."[20] However, other research indicates that while vinegar may increase the discharge from triggered stingers, it also prevents untriggered stingers from discharging; since the majority of stingers do not trigger immediately, the Australian Resuscitation Council continues to recommend using vinegar.[21]

Treatment is symptomatic, with antihistamines and anti-hypertensive drugs used to control inflammation and hypertension; intravenous opioids, such as morphine and fentanyl, are used to control the pain.[20] Magnesium sulfate has been used to reduce pain and hypertension in Irukandji syndrome,[22] although it has had no effect in other cases.[23]

Irukandji jellyfish are usually found near the coast, attracted by the warmer water, but blooms have been seen as far as five kilometres offshore. When properly treated, a single sting is normally not fatal, but two people in Australia are believed to have died from Irukandji stings in 2002 during a rash of incidents on Australia's northern coast attributed to these jellyfish[3][24][25][26]—greatly increasing public awareness of Irukandji syndrome. It is unknown how many other deaths from Irukandji syndrome have been wrongly attributed to other causes. It is also unknown which jellyfish species can cause Irukandji syndrome apart from Carukia barnesi and Malo kingi.[27]

STANDY

··schizophrenic pizza orderer and watch collectorNasty buggers irukandji

Guy up here was helicoptered off a fishing boat after getting one on he’s lip that flicked up as he was netting a fishing.

Guy up here was helicoptered off a fishing boat after getting one on he’s lip that flicked up as he was netting a fishing.

queriver

·This guy seems friendly enough...

https://www.cairnspost.com.au/news/...q/news-story/85593251921992fc03c5fcf475e20009

The article is behind a paywall defended by an angry 50kg 1.5m tall cassowary with dagger-like claws. 😲

https://theculturetrip.com/pacific/...t-dangerous-bird-7-facts-about-the-cassowary/

rob#1

·The article is behind a paywall defended by an angry 50kg 1.5m tall cassowary with dagger-like claws. 😲

https://theculturetrip.com/pacific/...t-dangerous-bird-7-facts-about-the-cassowary/

Ah, sorry about that - bloody paywalls. It’s weird as it works at my end. Basically the guy has a friendly cassowary pop in and visit regularly while he goes about his work. I’d be terrified of the damage it could do to my body, but he’s pretty chilled about it...😵💫

jetkins

·

Let's do the Time Warp again. 😉

https://omegaforums.net/threads/not...a-want-to-kill-you.52439/page-11#post-1106662

https://omegaforums.net/threads/not...a-want-to-kill-you.52439/page-11#post-1106662

Wryfox

·STANDY

··schizophrenic pizza orderer and watch collectorApparently everything in your picture can kill you.

Barbie

https://service.mattel.com/us/recall/j9472_IVR.asp?prod=

https://www.poison.org/articles/2012-oct/toy-magnets-are-dangerous-for-children

The Shrimp

https://www.health.nsw.gov.au/Infectious/factsheets/Pages/seafood_poisoning.aspx

The BBQ

https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/he...le-barbeques-after-sons-accidental-death.html

rob#1

·Outback Uber - the title says it all 😉. None of these things are remotely interested in killing you...

https://www.theguardian.com/environ...rn-australia-kununurra?CMP=Share_iOSApp_Other

https://www.theguardian.com/environ...rn-australia-kununurra?CMP=Share_iOSApp_Other

1972Steve

·The article is behind a paywall defended by an angry 50kg 1.5m tall cassowary with dagger-like claws. 😲

https://theculturetrip.com/pacific/...t-dangerous-bird-7-facts-about-the-cassowary/

It’s like it’s from Jurassic Park.

rob#1

·More snake craziness - but this time you’ve got to feel sorry for the snake. Paralysis ticks are nasty buggers

https://au.news.yahoo.com/snake-catchers-skin-crawling-find-backyard-pool-061238731.html

https://au.news.yahoo.com/snake-catchers-skin-crawling-find-backyard-pool-061238731.html