Longines and Omega

Longines and Omega

Within the context of vintage watch collecting, Longines and Omega share some important, broad similarities. They both hold clear places in the “mid-high” category, as judged by their production during the golden era of watchmaking (i.e. roughly the early 1940s through the early ‘60s). They both designed and produced several outstanding, workhorse calibers (e.g. 30mm, 30L, etc.), and also made strong, lasting impacts with specialty watches (e.g. divers, chronographs, etc.).

One interesting divergence, relatively speaking, occurred in an exalted category: chronometers produced for the consumer market. Omega was (and remains) very well known for the impressive array of wristwatch chronometers that it produced, beginning with the superb 30T2Rg in 1943. Their 30mm movements, with either the Rg or swan-neck regulators, subsequently became the base for a large number of automatic chronometers, as well. Any cursory review of the Observatory trials from the period will confirm the success that Omega enjoyed in producing competition chronometers, and the company’s sales records underscore, at least in part, the success of a marketing strategy that emphasized the production of chronometers for consumers.

Conversely, Longines chose not to emphasize wristwatch chronometers to nearly the same degree, at least through the 1950s. They did produce and market a relatively small number of Flagship chronometers, tuning the already excellent cal. 30L movement so that its performance potential matched that of its high-class competitors. They also produced the fine Observatory calibers 30Z and 30B, and, as a related aside, regularly marketed their sports timers (i.e. stopwatches, etc.) through associations with the Olympics and other organized sports. There is, however, an interesting and relatively little known chapter of Longines’ history as it pertains to wristwatch chronometer development. It begins in the early 1940s, and closer look will help to illuminate an important transition for both the company and the Observatory trial competitions.

Neuchâtel Observatory Trials

While a few wristwatches were submitted to other Observatory trials held in previous years (notably Rolex and Omega at Teddington), the importance of such trials, especially those held in the Swiss cantons of Neuchâtel and Genève, began to grow considerably when new rules and criteria for wristwatches (or, more precisely "wrist chronometres") were developed in 1941. Looking at the table listed below, one can’t help but notice certain patterns. Omega, for example, showed great consistency from 1943 onwards - a testament to the quality of their 30mm movements, while Zenith became a major player with the development of its iconic cal. 135.

But note also the early success enjoyed by Longines, unequivocally the dominant manufacturer represented at Neuchâtel in the early through mid-‘40s. What accounted for such extraordinary successes? Furthermore, what happened in 1949, when Longines experienced a stunning drop from those dizzying heights to a period of drought until the mid-‘50s? Those are questions that I hadn’t considered until a recent acquisition piqued my interest.

The Big Boys: 14.68Z and 15.68Z

The Big Boys: 14.68Z and 15.68Z

Collectors of vintage military watches are keenly aware of Longines’ contributions to the genre. Such collectors often focus on the large, distinctive, cushion-cased watches of Czech army origin, which feature the excellent cal. 15.68Z. These were 14.5 ligne (34mm) movements, first produced in 1939, and are strikingly similar in design to the smaller, very successful, and far more widely produced caliber 12.68Z (27mm). These calibers came in both “Z” and “N” versions, the latter being center second, and the former sub-second. Here is an example of the 15 jewel 15.68Z caliber found in the oversized military watches:

Beginning with the 1941 Neuchâtel trials, the maximum diameter for a competition wristwatch caliber was restricted to 34mm. There were only six watches entered that year, and only three of those received certificates. Longines entered the fray the following year with cal. 15.68Z, some nearly identical cal. 14.68Z (more on this later), and a smaller number of 12.68Z movements. The results speak for themselves, as those movements dominated their competition for five consecutive years, and stood atop the standings in six of seven annual trials through 1948.

The mystery of why Longines fell so sharply from its dominant position is, as it turns out, rather easily explained. In 1948, the Swiss Observatories imposed a new limit of 30mm in the wrist chronometer category. So, in one fell swoop, Longines' larger diameter movements were excluded, and it was forced to begin to play catch-up with Omega and Zenith, companies which had already been focusing on 30mm movements for a number of years.

As an interesting aside, Longines did enter and achieve success with the 15.68Z movements in the Geneva trials well into the 1950s. This was not because the wrist chronometer standards were different from those at Neuchâtel, but rather because there was a

“poche petit” (small pocket) category of 30–38mm. 1957 was, apparently, the final year that a 15.68Z movement was entered in competition.

As mentioned earlier, it is clear that Longines chose not to emphasize their successes at the Observatory trials through advertising to nearly the degree as Omega (or Rolex and Zenith, for that matter). They also chose not to produce many chronometers for public consumption. Actually, that is an understatement. Longines is, like most manufacturers, rather tight-lipped about its historical production numbers, but it is clear that in the context of manual-wind chronometers produced during the ‘40s and ‘50s, the company sold very few to consumers. Furthermore, if one excludes the Flagship chronometers of the mid-late ‘50s, the number most certainly becomes very small indeed. Having said all of that, I was able to find one advertisement from the 1940s trumpeting Longines' success with their 14/15.68Z movements. Note that they are referred to as 33mm movements in the advertisement, which raises some other questions as well.

As Luck Would Have It

As Luck Would Have It

There are a number of variables that contribute to the acquisition of a fine, rare and desirable vintage watch, but luck, especially as it relates to timing, may well be the most important. I do enjoy an advantage over some in that I am self-employed, and have a fair number of opportunities to search the web for interesting watches that are fresh to market. But the vintage watch gods must have also been smiling when I happened across the chronometer that is the subject of this post.

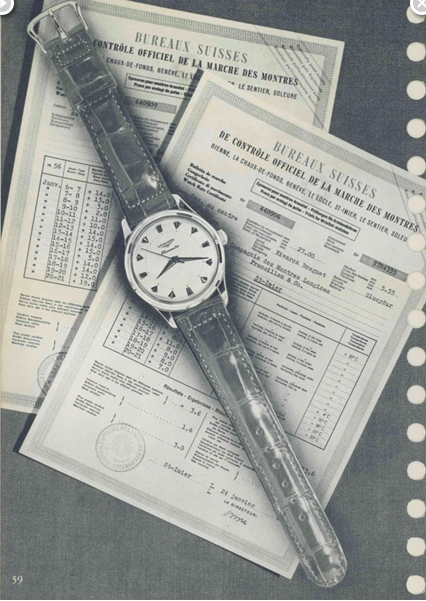

It is a reference 6059, cased in 18k yellow gold. It is powered by a 17j cal. 14.68Z chronometer movement, bimetallic split rim balance, and Breguet overcoil hairspring. It is 36mm in diameter excluding the crown, and, with the exception of the mainspring, which was replaced during a recent service, is, to my knowledge, fully original. It was originally invoiced to Messrs. Ostersetzer, who were at the time Longines’ Italian agent, on July 11, 1953. The movement dates to around 1947-48, but rather large disparities between production and sale dates were not uncommon at the time, especially in the case of low production movements.

Like many collectors, I don’t acquire watches solely for their historical significance, or even because of some particularly impressive technical characteristic(s). I insist, first and foremost, that they be both attractive and wearable, and anything beyond that is a bonus. On rare occasions, I come across a watch that truly satisfies in

every respect, and this is most certainly one of those.

The wrist presence, a characteristic that I believe to be often underrated, is tremendous. Keep in mind that the cal. 14.68Z is not only 34mm in diameter, but 5.2mm high, over three times the height of V&C’s ultra-thin cal. 1003 which measures 1.65mm. So this watch has real substance, a quality that I happen to like, especially in such a beautifully designed and balanced case. It also features an exceptional crown that compliments the substantial case perfectly. The dial is a classic '50s design, featuring a large, sunken sub-second dial. The applied markers and Longines logo are, of course, made of gold, as are the hands. In fact, I'm fairly certain that the hour and minute hands have a higher gold content than was typical of the era, as they show no degradation whatsoever, which is unusual.

Cal. 14.68Z: Questions, Answers, and Speculation

Cal. 14.68Z: Questions, Answers, and Speculation

I mentioned earlier that the cal. 14.68Z is virtually identical to the cal. 15.68Z. This is reflected in the Longines materials sheet seen below, as there was apparently no point in creating two separate sheets. But this is where things become a bit unclear, as, for example (and alluded to earlier), the 15.68Z is listed as having a diameter of 34mm, while the 14.68Z is listed at 33mm. Now why would two movements that are nearly identical be produced with one being a mere one mm wider than the other? And isn't it interesting that the advertisement posted above lists the diameter of the Observatory movements as 33mm? Before I continue, I want to give great credit to Jennifer Bochud, Museum Curator in the Longines Historical Department. Jennifer, as some collectors know, is extremely helpful when supplying historical information, and she went far beyond her usual call of duty when kindly researching and answering some of my esoteric questions about this particular chronometer.

From what I can gather, the relationship of the 15.68Z and 14.68Z calibers is somewhat, if not closely analogous to Movado’s cal. 125 and 126. The cal. 125 was widely produced, while the low-production cal. 126 was the chronometer version, and shared most of the same parts. What is interesting is that while the cal. 126 featured clear, distinguishing characteristics, the number “125” was still found on its barrel bridge. In the case of the subject chronometer, it is recorded by Longines in the archives as a cal. 14.68Z, yet 15.68Z is etched below the balance.

There are other reasons that lead me to believe that the 14.68Z was used primarily, if not exclusively as a chronometer version of the 15.68Z. Not only do searches of the web produce remarkably few references to the former caliber, but even Ms. Bochud, with the great benefit of access to the expertise of Longines watchmakers and historical records, was able to find very little specific information on the caliber. She was not even able to confirm whether or not any 14.68Z movements were sold in non-chronometer form!

There are at least two telltale differences between the standard version of the 15.68Z and subject 14.68Z chronometer, and they are consistent with the primary distinctions between the subsequent Flagship chronometers and the basic 30L movements: the regulator tails are truncated in order to accommodate Breguet overcoil hairsprings. Different balances were almost certain to have been used on chronometer movements as well. Presumably these parts would also have been fitted on the 15.68Z movements that were produced for chronometer competitions, but an obvious question remains:

Why, if the 14.68Z was essentially a chronometer version of the 15.68Z, was the latter also entered into Observatory competitions?

Aside from the large balance, a characteristic which ties together most of the best calibers of the era, this 14.68Z is decorated with, to my eye, a particularly attractive version of

Côtes de Genève (i.e. Geneva Stripes). Further underscoring the special nature of the movement, you can see the same stripes below on the bottom plate (in the second image), which would only be seen on disassembly by a watchmaker! And speaking of watchmakers, I’d like to thank mine, Keaton Myrick, for his insights into, and work on this movement, as well as many of the fine photos used in this post.

There was no shock absorbing technology employed, which is consistent with other watches that were designed for Observatory testing, and it is also interesting to note that unlike what collectors have come to expect of most chronometers of the era, there were no inscriptions on the bridges relating to adjustments, or otherwise identifying these movements as being special. That understated approach - allowing the finely finished movement and its performance to do the talking - appeals to me greatly.

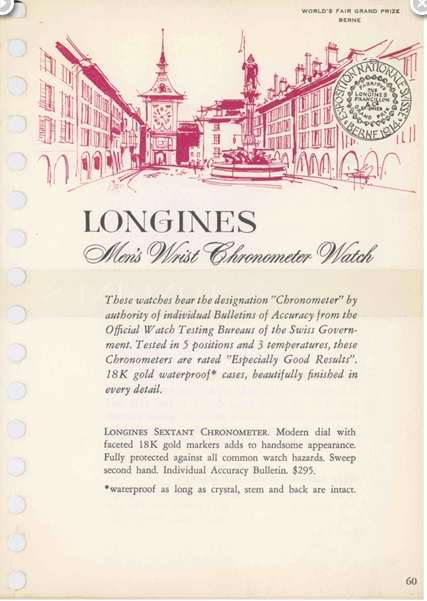

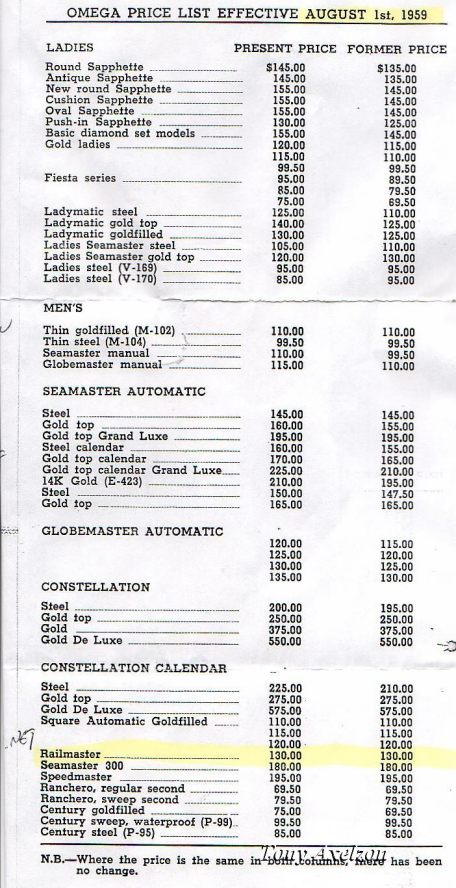

Based on the image seen below, taken from a Swiss catalogue, and converting to 1950 dollars, the cost of (what I believe to be) a 12.68Z chronometer in 1953 would have been roughly 140 dollars. That certainly wasn’t inexpensive, given that the average automobile cost around $1,500 at the time, though the new to market automatic

Seamaster and

Constellation chronometers in 18k were, for comparison, catalogued the same year at 950 Swiss francs. I suspect that the 14.68Z would have been slightly more expensive than the 12.68Z version, but am unable to confirm that hypothesis.

As a final note, this is yet another example of why I find vintage watch collecting to be so compelling. By that I don't simply mean being lucky enough to find and acquire a special watch, but rather the way in which an acquisition - or merely research into a

possible acquisition - can lead to a fascinating and exciting journey. Thanks for joining me on this particular one - I hope that you enjoyed it!

Cheers,

Tony C.