cvalue13

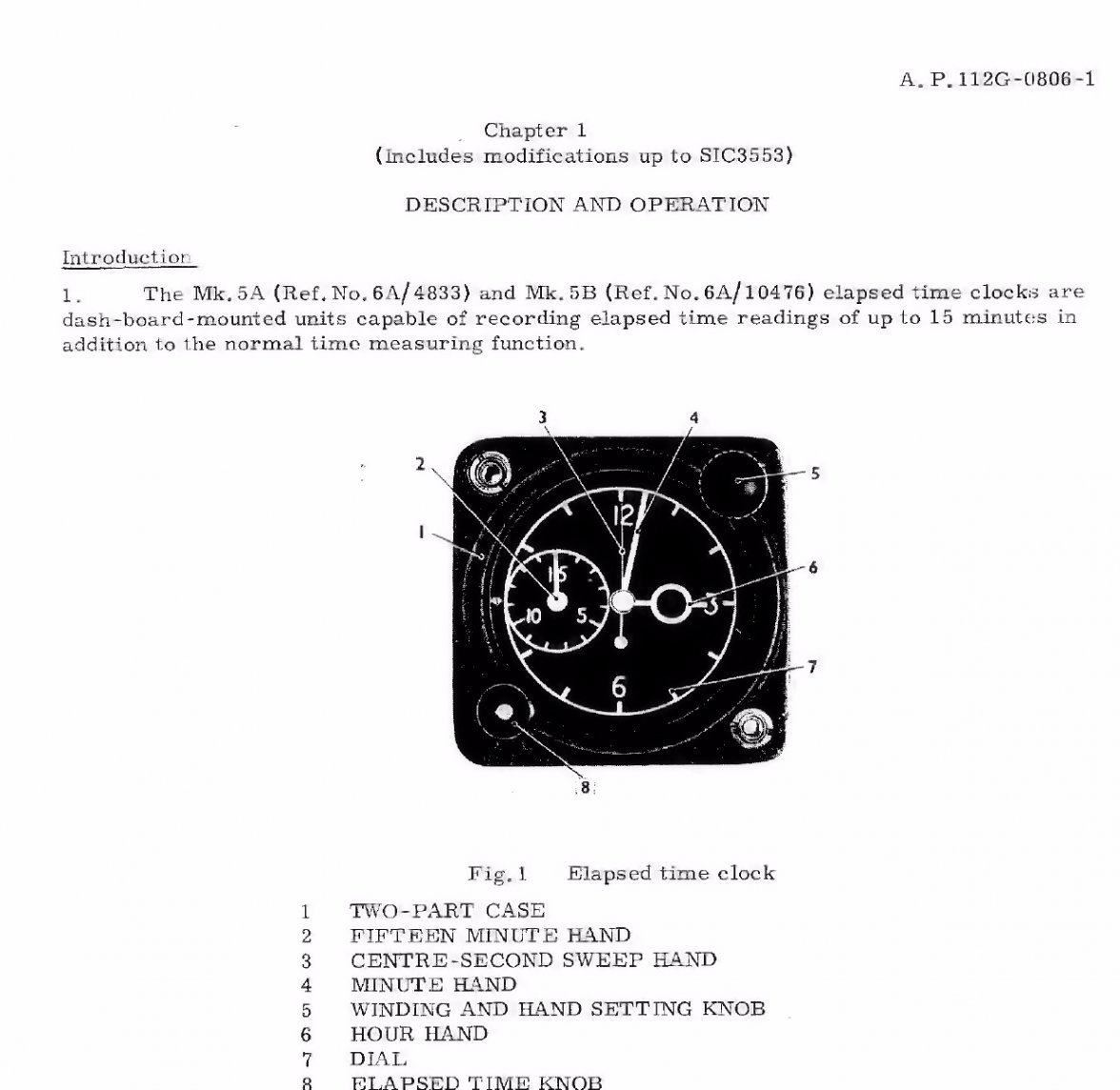

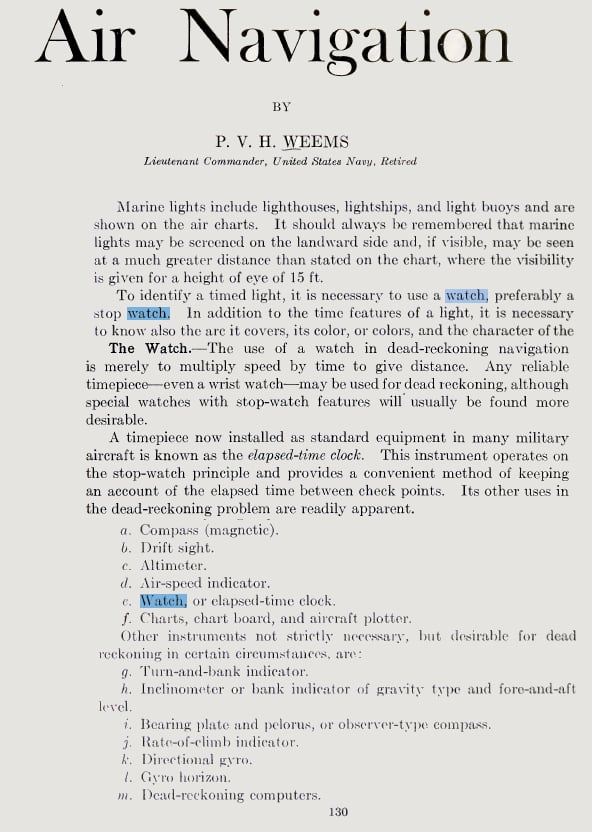

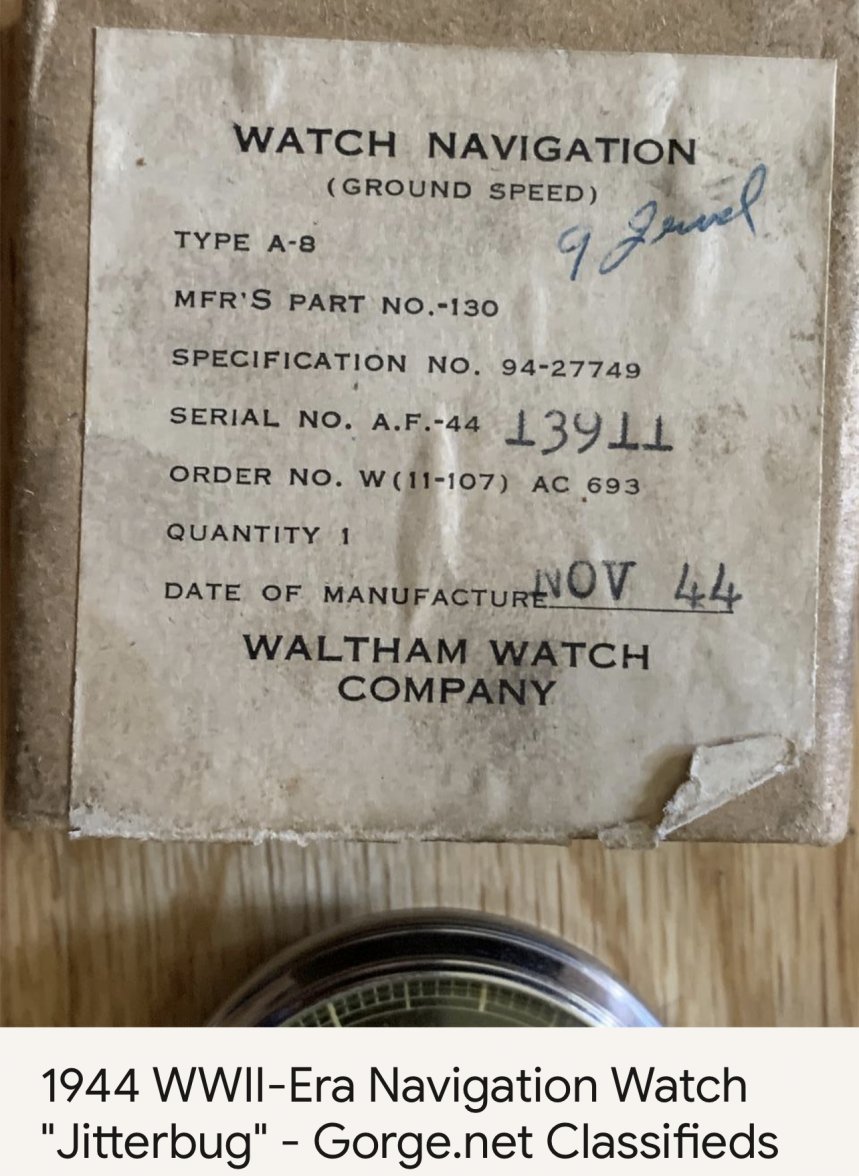

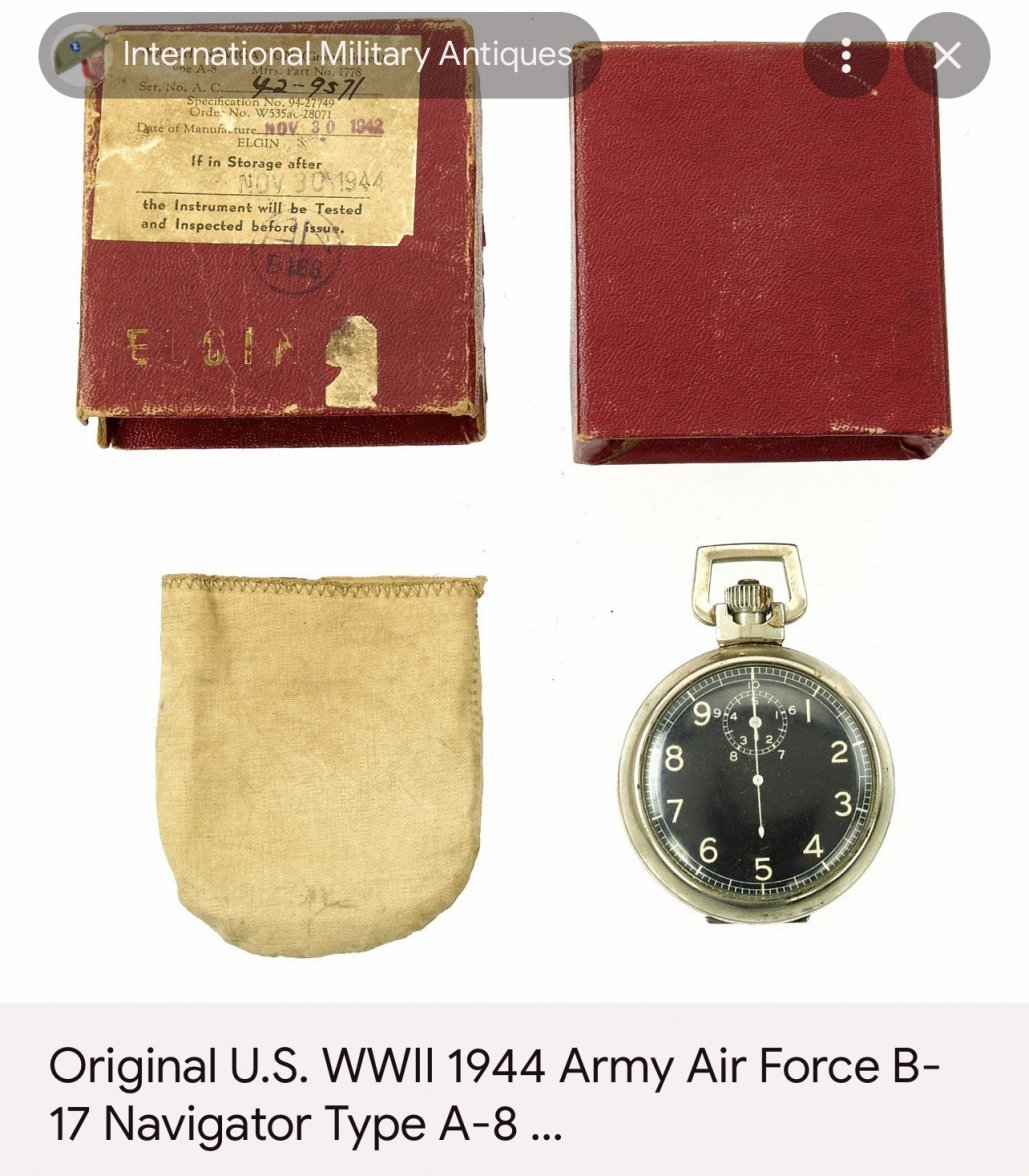

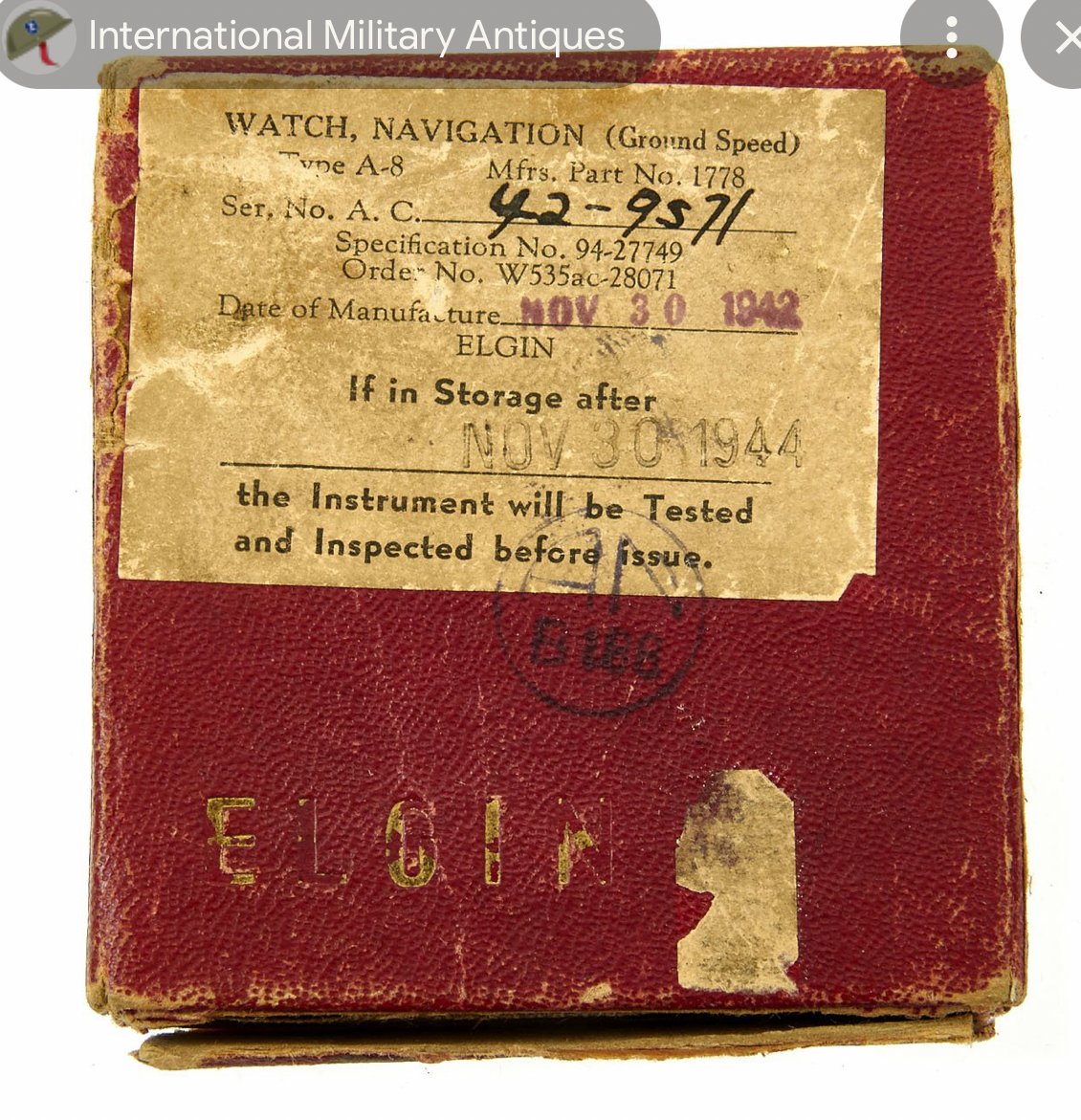

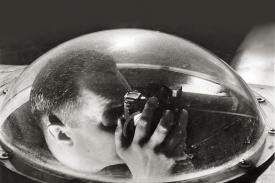

·The last several posts were spent on better proving up that chronographs were useful to pilots whatsoever (surprised that needed further vetting, but here we are), that they were used for navigation despite the existence of other tools onboard (as redundancy, or confirmatory, or because pilots weren’t always in machines they knew/trusted u like their wrist piece), and - with the jitterbug - that navigators widely utilized chronographs/stopwatches that ran out to a maximum of 10 minutes, suggesting that lesser increments of time were critical to some portion of navigation.

Here’s where I’ll start then turning toward the specific issue of 6 minute increments (or other decimal-time simple units of time) being among the sub-10 minute units of time important to pilots and/or aeronautic navigators (for that matter, maritime navigators for the same reasons).

I’ve come to understand that historical “dead reckoning” in many ways differs from the modern concept of DR, and that the historical sense may be more relevant to these 3 and 6 minute increments. So, when asking contemporary pilots, e.g., “what does 6 minutes have to do with basic navigation” there is perhaps to some degree a blank stare because contemporary navigation is now so far removed from what pragmatic pilots did in the early- and mi-20th century.

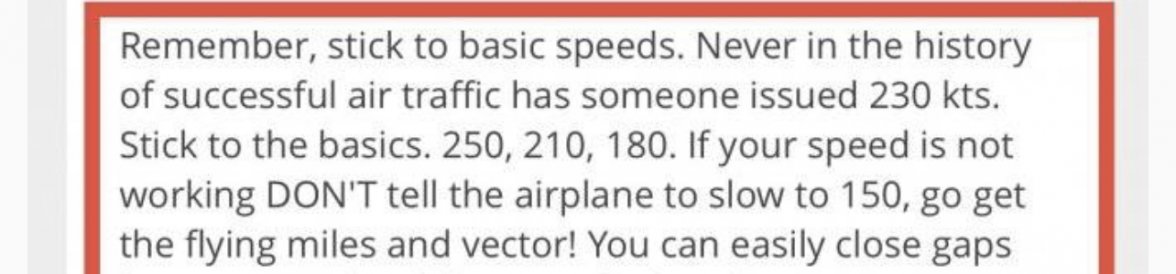

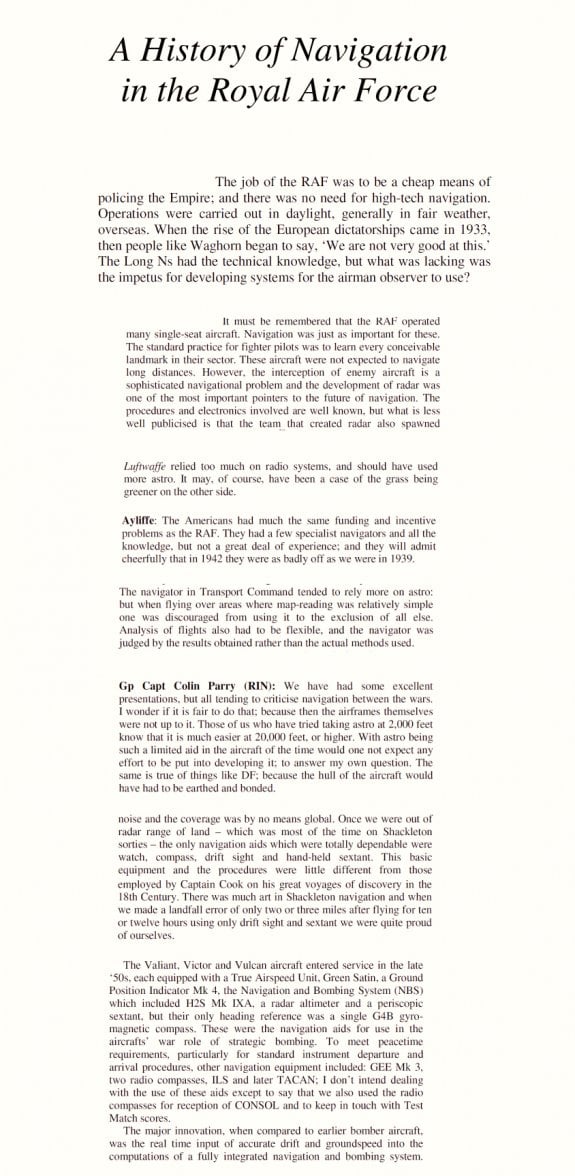

I’ve uncovered the following “sage” advice article from 1948, written by an author who appears to know his stuff about how military pilots actually navigated (and suggesting other pilot’s follow suit):

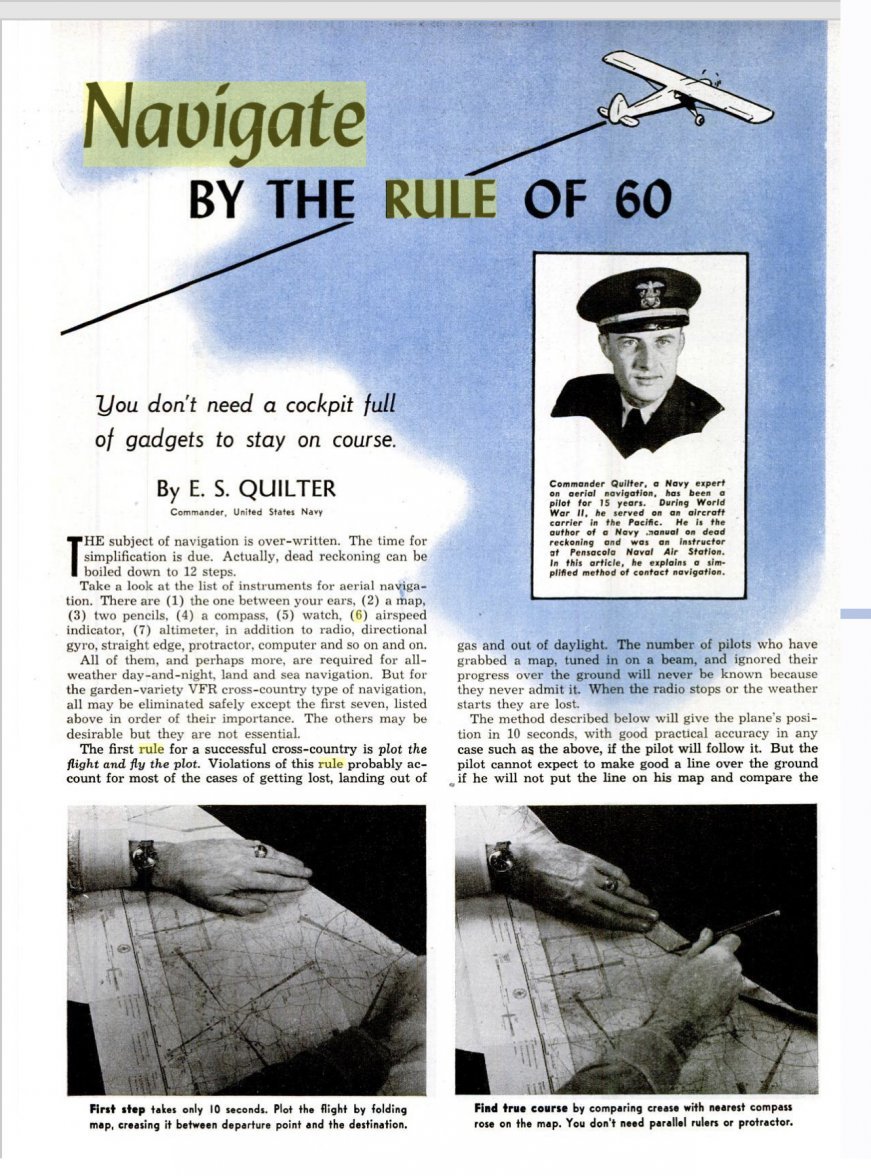

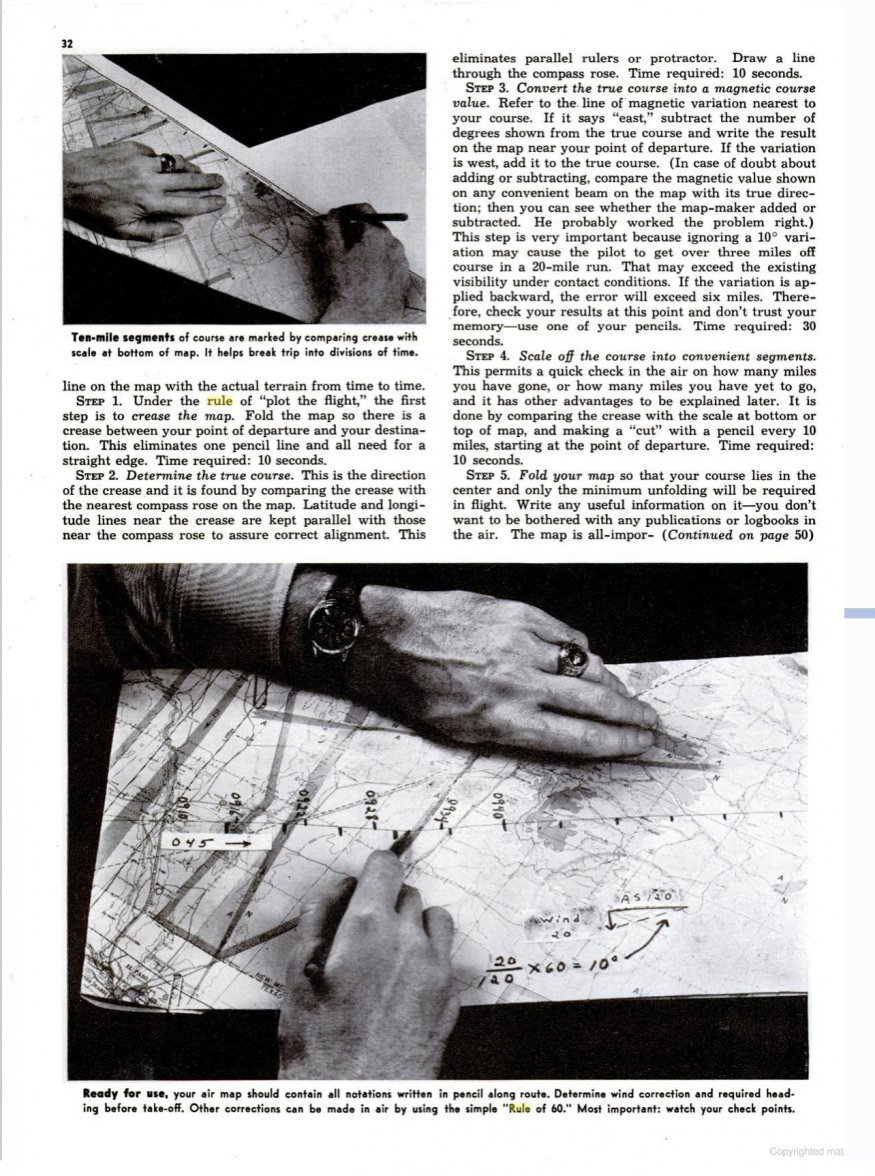

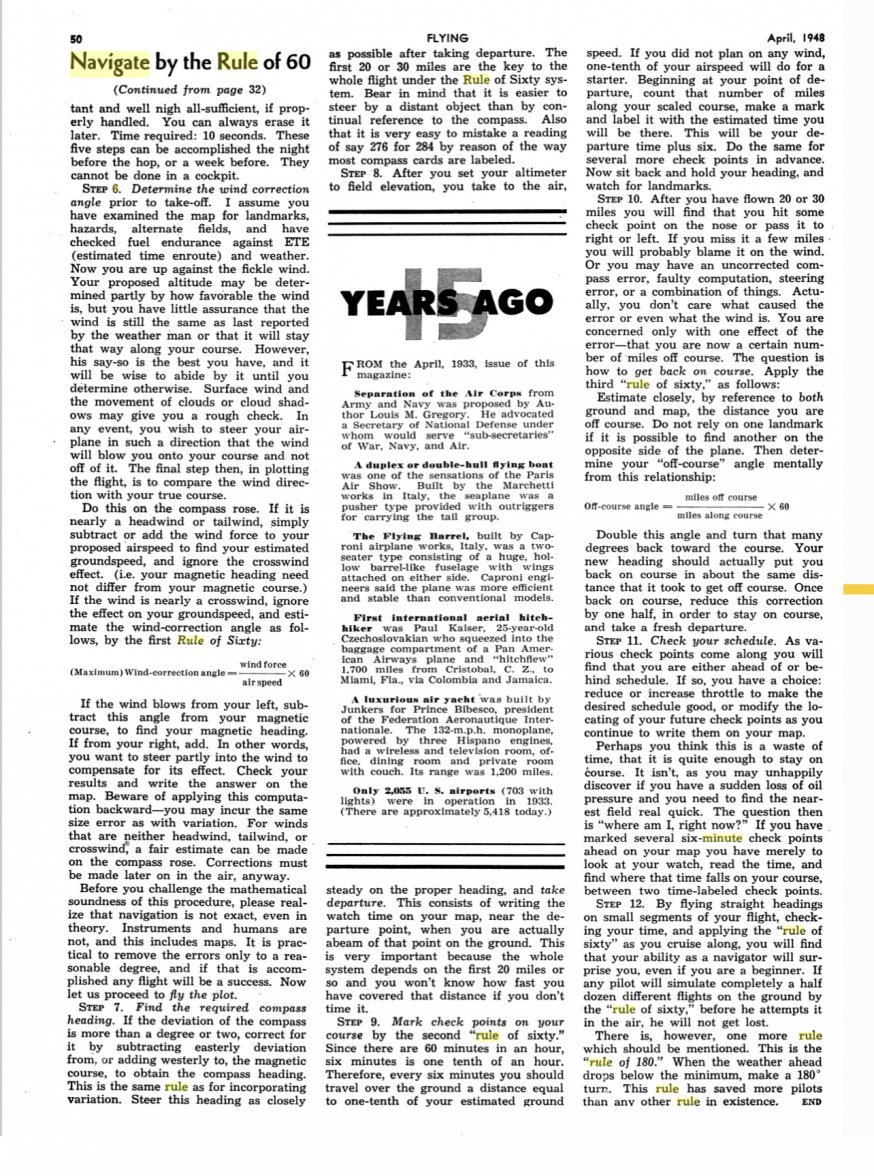

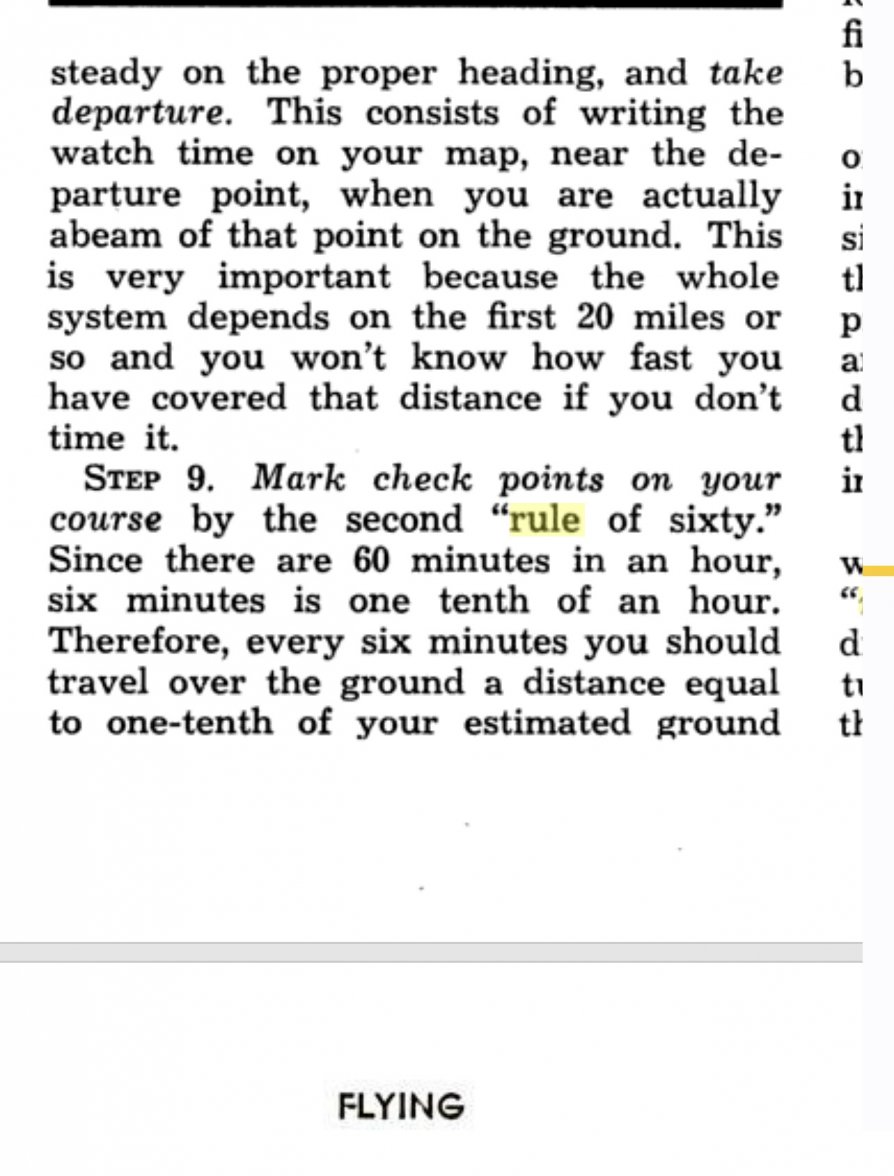

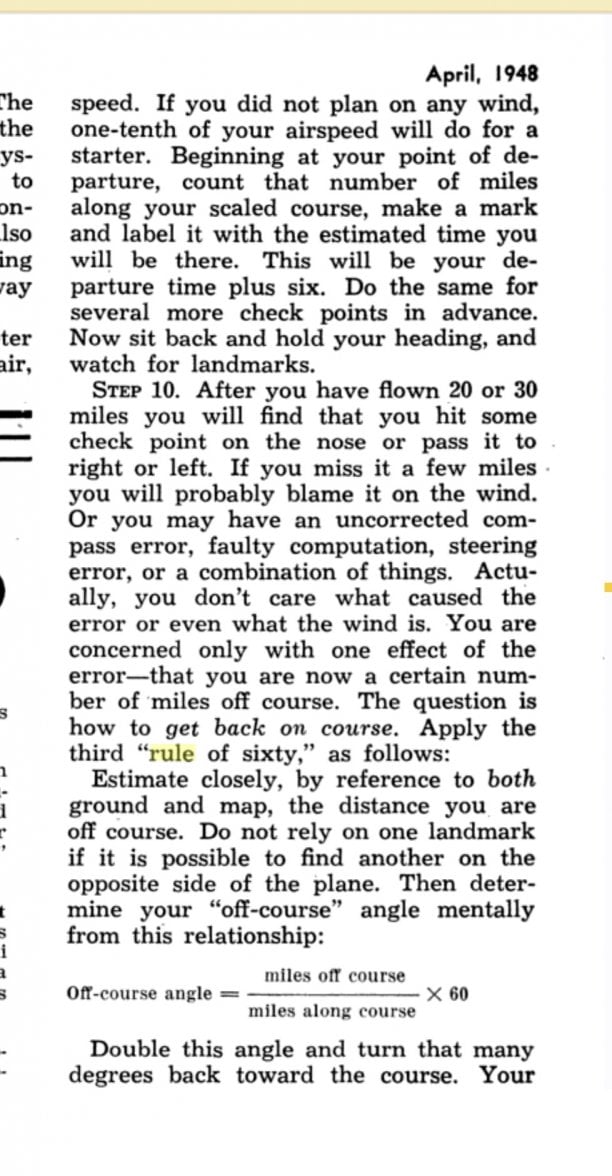

In the article, he’s basically arguing that all the newfangled gadgetry is not only unnecessary but even unhelpful to a pilot. I’m adding the article here in full, with the relevant portions RE 6 minute increments being at the final page middle column (near the bottom) and running into the far right column (toward the top).

It would be great to also find more first-hand accounts of this type of approach to navigation being common enough to cause watch manufacturers to adjust their chronograph designs to reflect the importance of the 6 minute (or 3 minute increments) for marketing toward general aviation. I’m turning toward those and related efforts.

I also suspect that this style of flying described in the article, particularly where there was not the luxury of time in cockpit for better accuracy, was specifically useful to military pilots (the author of this pop piece is the military instructor afterall) - possibly explaining why several mil spec watches went above and beyond to emphasize the 3/6 minute increments and legibility. More direct evidence for the manufacture of those watches also would be great, and I’ll turn toward that as well.

But for now, I thought this piece - as a singular exhibit - was wonderfully instructive as to the type of flying occurring in the military before this 1948 article, and that was as a methodology being propagated in the post-war general aviation boom.

This is not the only “exhibit” proving up that, in essence, the pragmatic pilot of the early- and mid-20th century traded in time increments of 6 (or 3) when it came to any number of calculations relevant to pilotage and navigation. What I’ve taken away from these materials I’ve found and reviewed, is that these pilots (or navigators) saw the world in increments of - essentially - decimal time. Hours and minutes if time, hours and minutes of latitude/longitude coordinates, the 360 degrees of cardinal directions (of heading, of wind direction, of magnetic distortions, on and on), etc., together create for a swirling mass of mathematics to track and on which their lives depended. Not letting the perfect be the enemy of the staying alive, navigation often revolved around core “rules of thumb” including viewing the world through 6-minute glasses (or other neatly divisible portions of 60).

This article is a neat little package of this type of thinking, showing various “rule of 60” and derivatives as the core skills argued as necessary to pragmatic navigation. Notably, a guy like this author, would seem to have no need or patience for a Breitling Navitimer with it’s slide rule functions (the rule if 6 is essentially a replacement for referencing a slide rule as relates to the S=D/T equation and it’s variations).

While reading the whole article will best give a glimpse of this approach to flying and seeing the world in 6/60/3 minute increments, at bottom I’ve excepted the bits precisely on point of the 6 minute rule (what the author places as his “step 9” in how to really fly).

Here’s where I’ll start then turning toward the specific issue of 6 minute increments (or other decimal-time simple units of time) being among the sub-10 minute units of time important to pilots and/or aeronautic navigators (for that matter, maritime navigators for the same reasons).

I’ve come to understand that historical “dead reckoning” in many ways differs from the modern concept of DR, and that the historical sense may be more relevant to these 3 and 6 minute increments. So, when asking contemporary pilots, e.g., “what does 6 minutes have to do with basic navigation” there is perhaps to some degree a blank stare because contemporary navigation is now so far removed from what pragmatic pilots did in the early- and mi-20th century.

I’ve uncovered the following “sage” advice article from 1948, written by an author who appears to know his stuff about how military pilots actually navigated (and suggesting other pilot’s follow suit):

In the article, he’s basically arguing that all the newfangled gadgetry is not only unnecessary but even unhelpful to a pilot. I’m adding the article here in full, with the relevant portions RE 6 minute increments being at the final page middle column (near the bottom) and running into the far right column (toward the top).

It would be great to also find more first-hand accounts of this type of approach to navigation being common enough to cause watch manufacturers to adjust their chronograph designs to reflect the importance of the 6 minute (or 3 minute increments) for marketing toward general aviation. I’m turning toward those and related efforts.

I also suspect that this style of flying described in the article, particularly where there was not the luxury of time in cockpit for better accuracy, was specifically useful to military pilots (the author of this pop piece is the military instructor afterall) - possibly explaining why several mil spec watches went above and beyond to emphasize the 3/6 minute increments and legibility. More direct evidence for the manufacture of those watches also would be great, and I’ll turn toward that as well.

But for now, I thought this piece - as a singular exhibit - was wonderfully instructive as to the type of flying occurring in the military before this 1948 article, and that was as a methodology being propagated in the post-war general aviation boom.

This is not the only “exhibit” proving up that, in essence, the pragmatic pilot of the early- and mid-20th century traded in time increments of 6 (or 3) when it came to any number of calculations relevant to pilotage and navigation. What I’ve taken away from these materials I’ve found and reviewed, is that these pilots (or navigators) saw the world in increments of - essentially - decimal time. Hours and minutes if time, hours and minutes of latitude/longitude coordinates, the 360 degrees of cardinal directions (of heading, of wind direction, of magnetic distortions, on and on), etc., together create for a swirling mass of mathematics to track and on which their lives depended. Not letting the perfect be the enemy of the staying alive, navigation often revolved around core “rules of thumb” including viewing the world through 6-minute glasses (or other neatly divisible portions of 60).

This article is a neat little package of this type of thinking, showing various “rule of 60” and derivatives as the core skills argued as necessary to pragmatic navigation. Notably, a guy like this author, would seem to have no need or patience for a Breitling Navitimer with it’s slide rule functions (the rule if 6 is essentially a replacement for referencing a slide rule as relates to the S=D/T equation and it’s variations).

While reading the whole article will best give a glimpse of this approach to flying and seeing the world in 6/60/3 minute increments, at bottom I’ve excepted the bits precisely on point of the 6 minute rule (what the author places as his “step 9” in how to really fly).