Following on the last two 1960’s Omega adds (run repetitively in various boating and flying magazines from ~1966-1969), and to try and clear some fundamental underbrush of skepticism:

Early in the thread, there was expressed some skepticism around the utility whatsoever of a wrist chronograph to flying.

I'm not a pilot but do pilots actually have time to fiddle with a watch making timing calculations? Seems they would have other things to worry about. I doubt many pilots actually used a chronograph in their flying duties, but maybe I'm wrong.

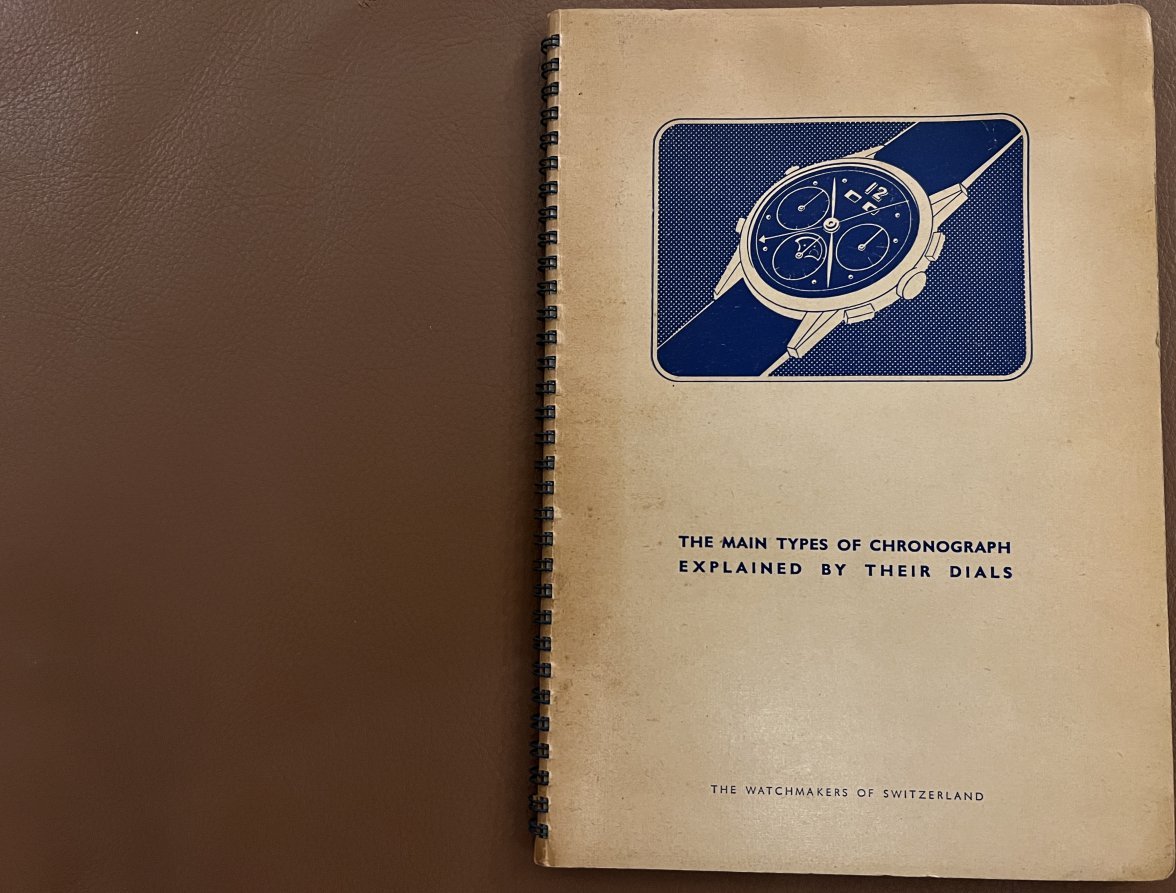

I’m the last one who should squint at skepticism, so as a preliminary matter I thought I would more thoroughly address this question regarding the general utility of chronographs to flying.

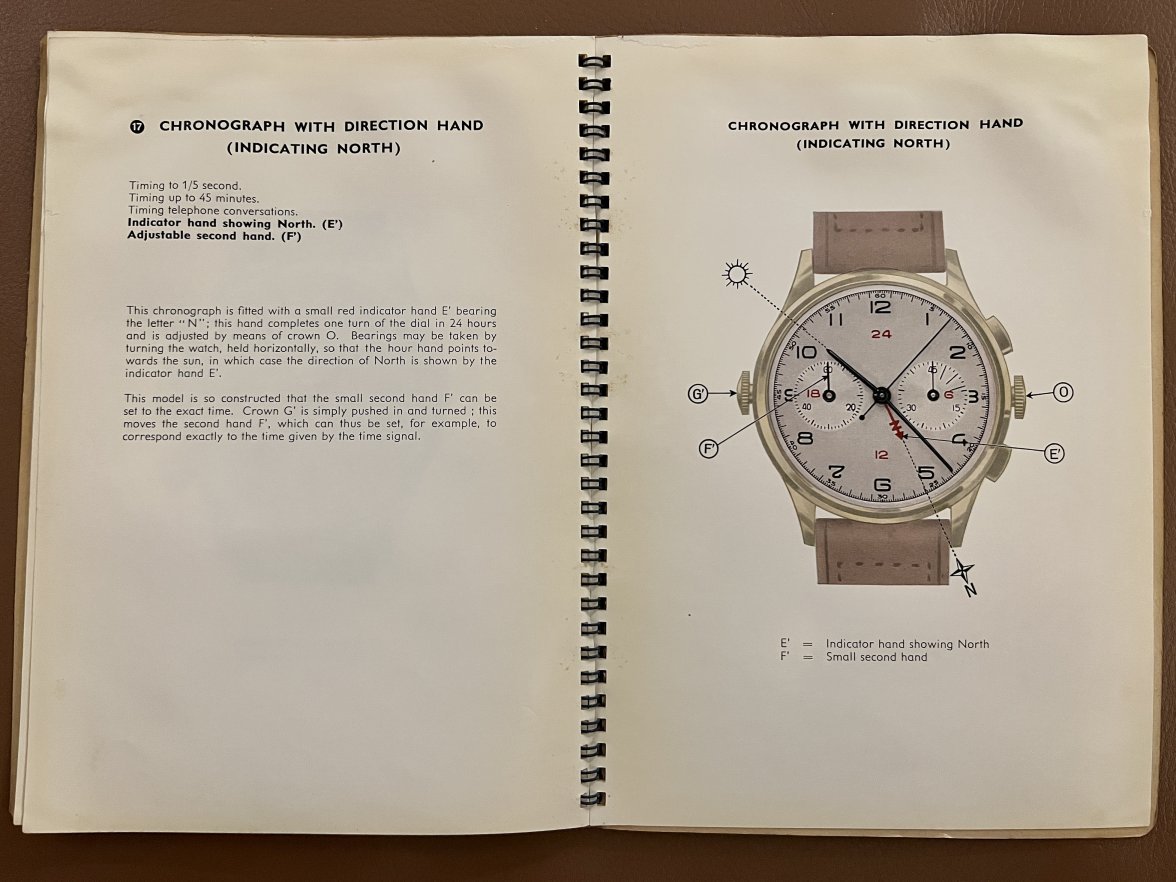

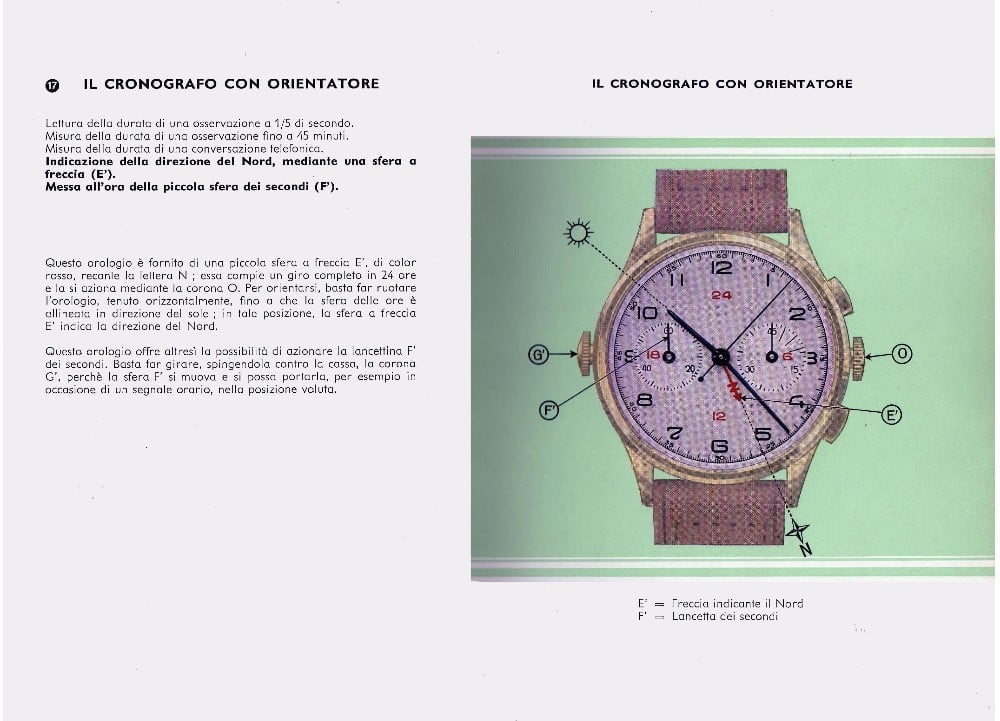

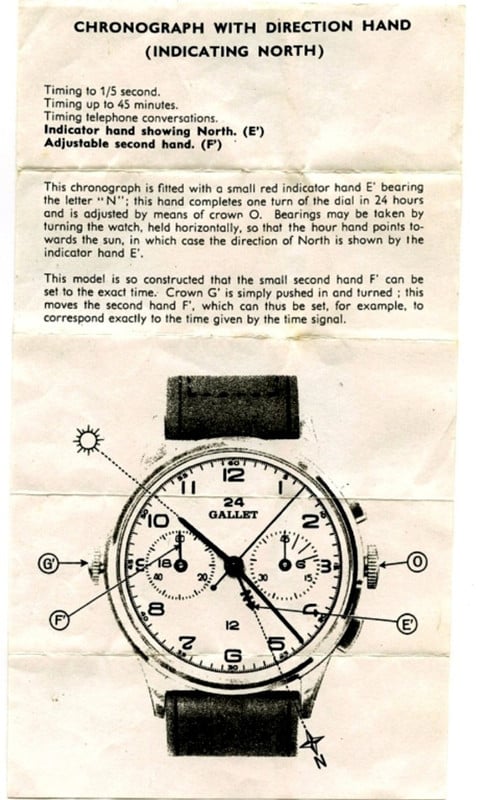

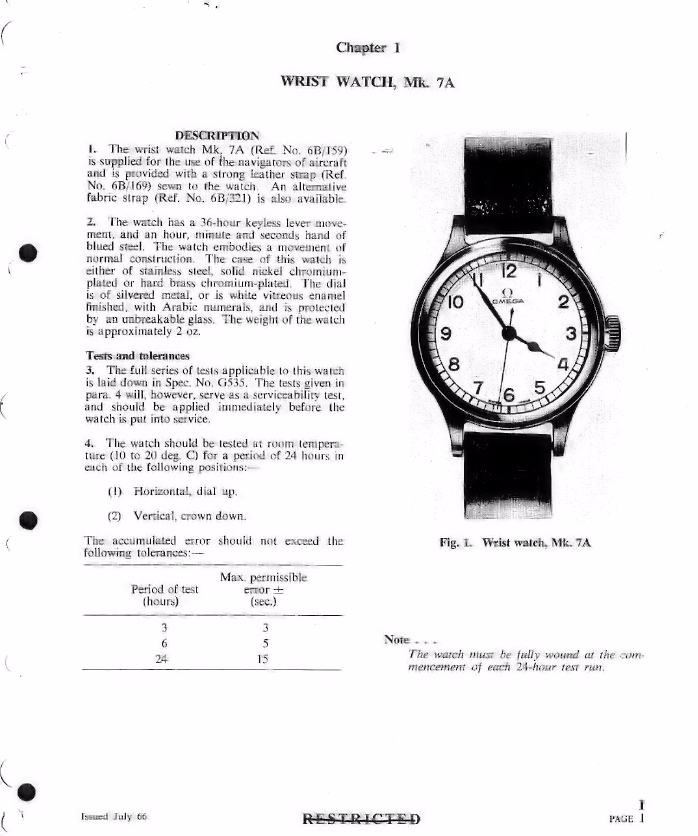

While my original post contained

a link to a navigational instruction document that revered the chronograph as the second most important instrument in a cockpit after the compass, that document was relatively contemporary and was perhaps viewed as lacking period authority.

I think it would be good to search for period advertising. Maybe some of the manufacturers promoted the markings as a feature. Or maybe one could find a book from the 1930s. That would be much less speculative.

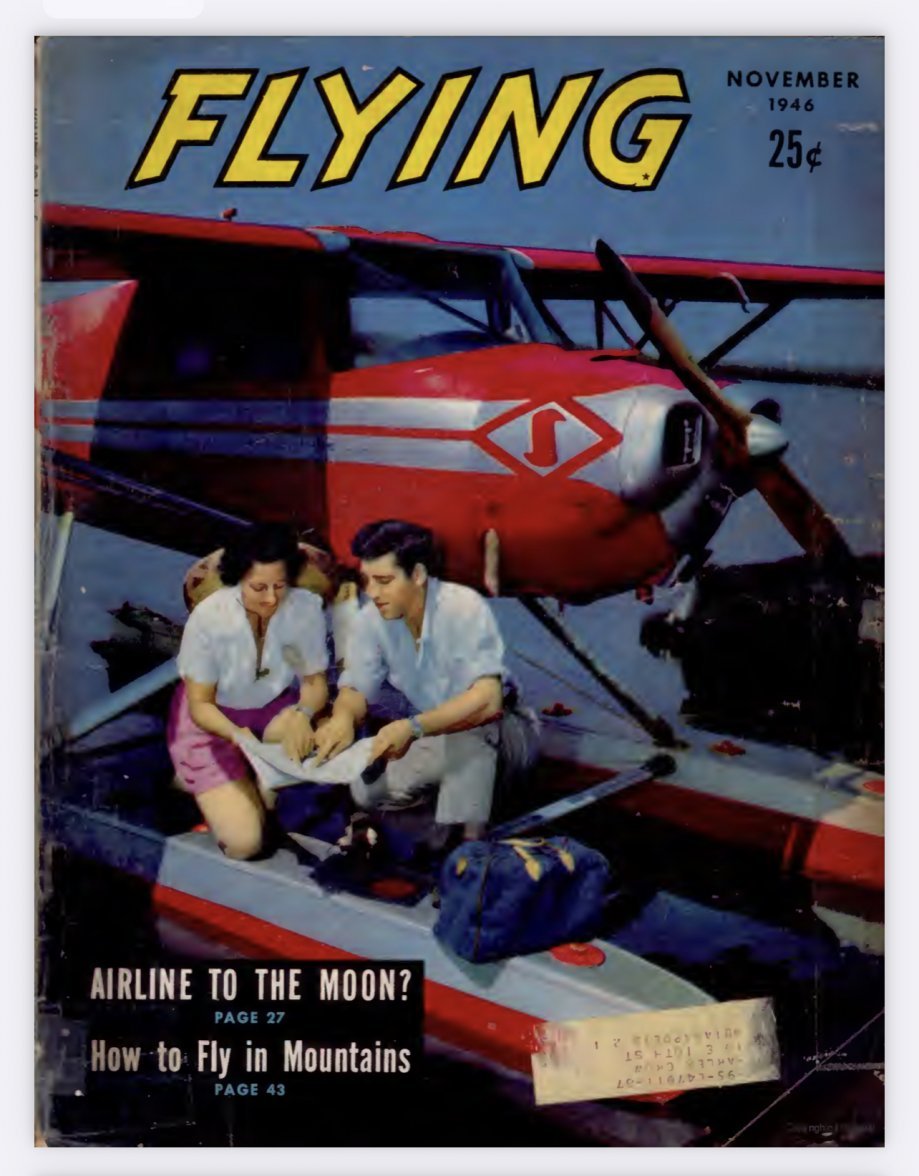

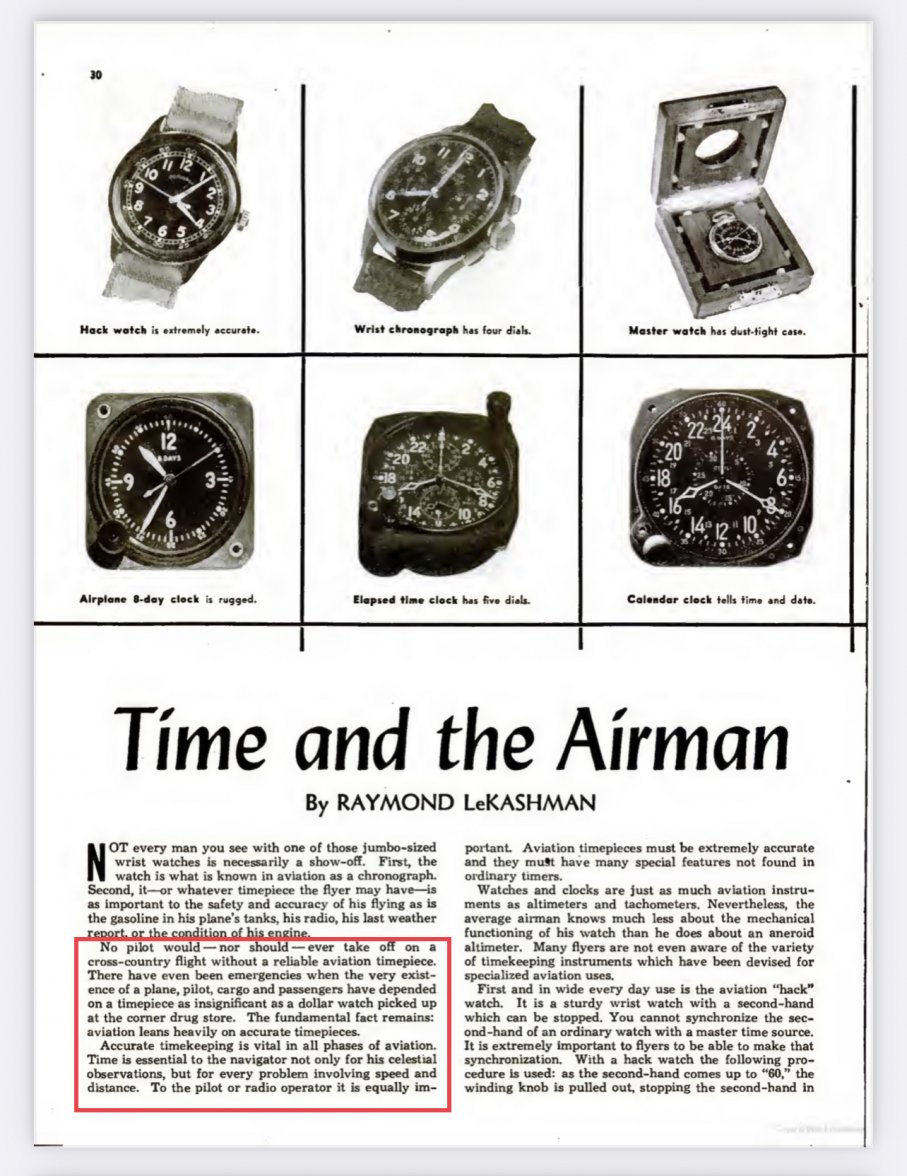

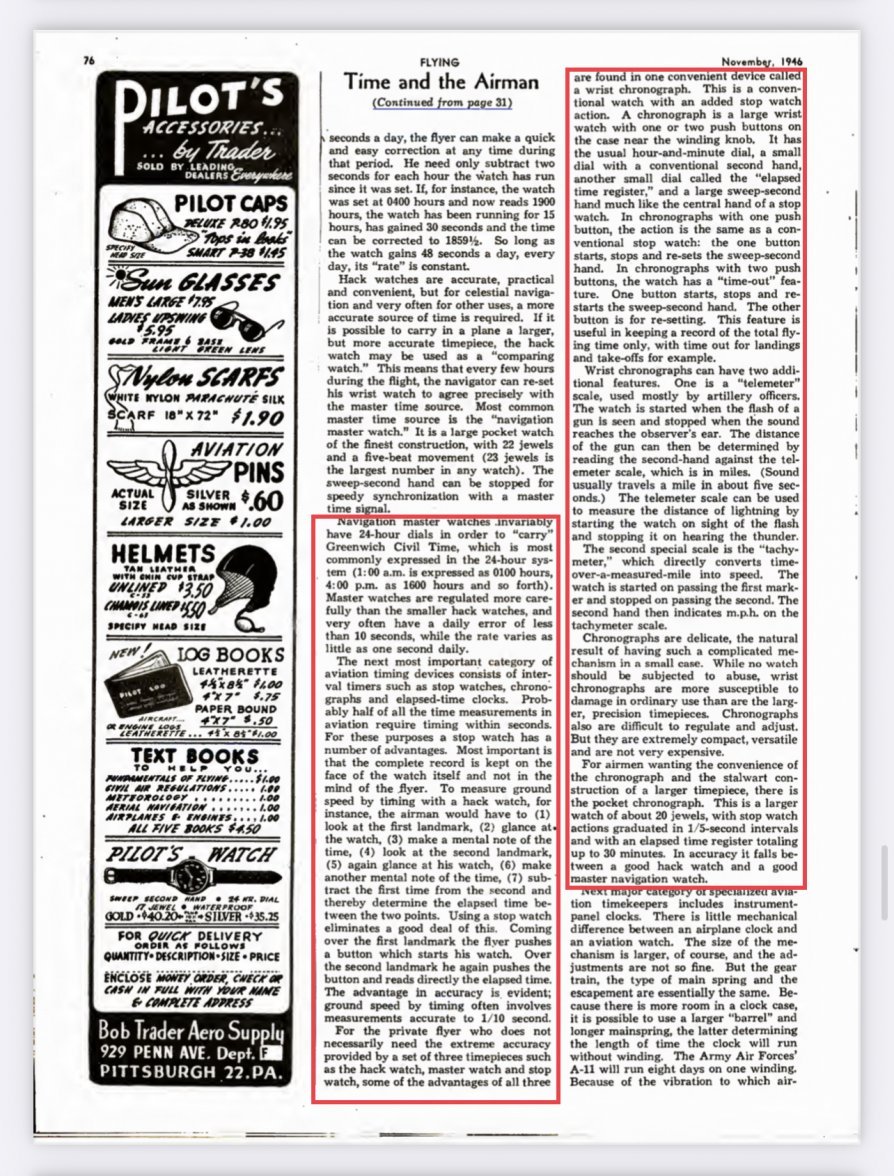

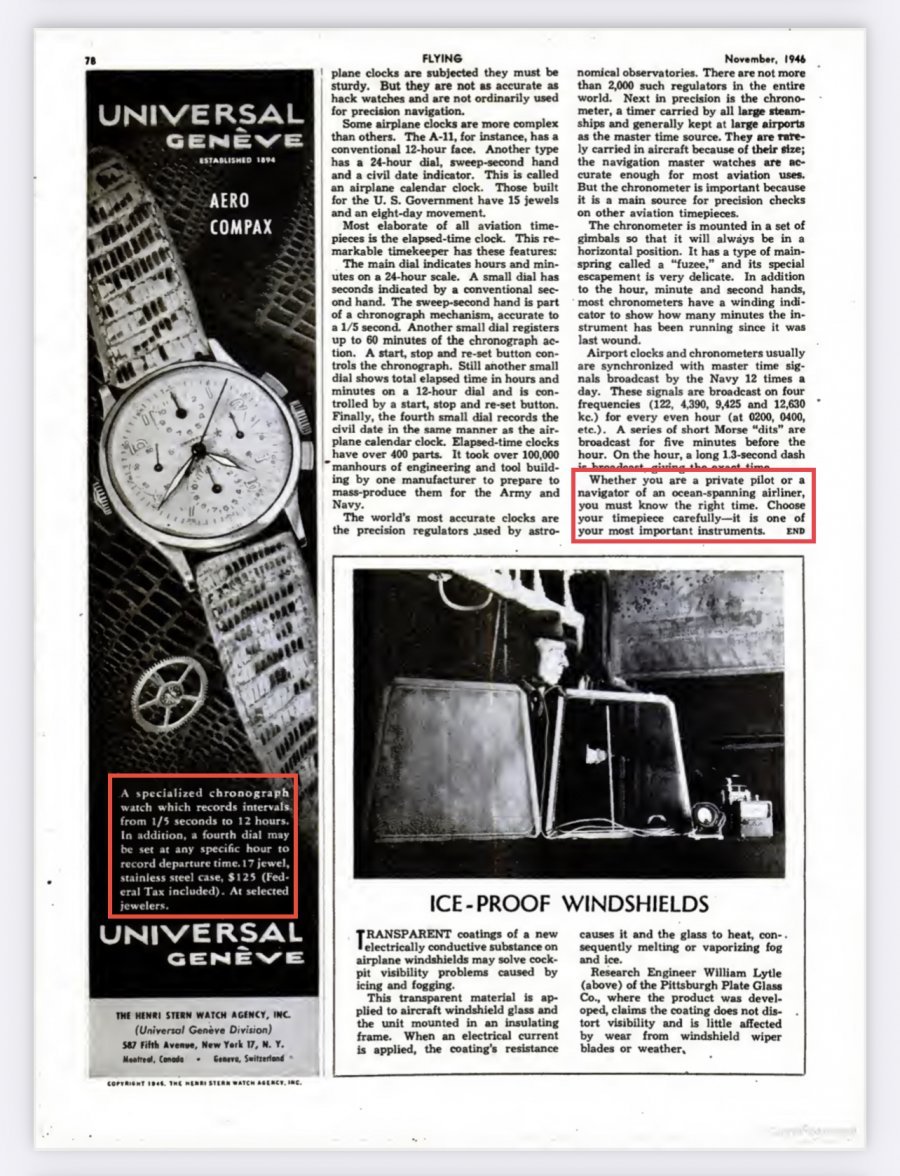

Below is an article from

Flying magazine, 1946, titled “Time and the Airman.” It covers broadly the utilization of chronographs and stopwatches to the airman, from on-board to the wrist.

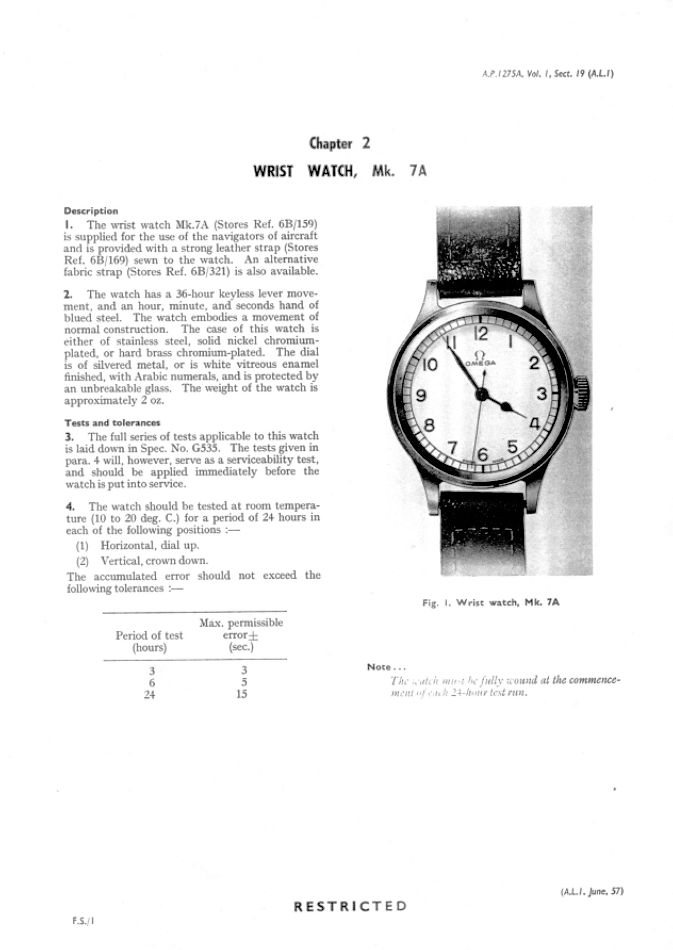

Relatedly, also earlier in this post there was expressed some skepticism about the utility of a wrist chronograph, when - I think the criticism goes - there would be various sorts of on-board instrumentation to perform navigational calculations.

I think it's more likely that a pilot who is relying on dead reckoning will know how fast he's going but not how far.

My original post also had content addressing this sub-point. But to briefly address this sub-topic of continued skepticism, I also include below a few additional period excerpts. Those excerpts, in short, show that variously pilots utilized their wrist chronographs as either primary or secondary navigational timers when, e.g., they had simple aircraft, or their aircraft mechanicals were malfunctioning, or they had occasion to disbelieve their aircraft mechanicals and utilized their wrist chronographs to perform confirmatory calculations and regain trust in their on-boards. (Moreover, while not addressed in my excerpts below, elsewhere there are discussions of pilots who were switching between aircrafts, they themselves did not maintain or know to have reliable instruments, preferring to have at least their own wrist watch with a “rate known” and personally-maintained certainty of accurate timekeeping.)

I should mention that there are exhaustive historical materials that either directly or by inference make it absolutely undeniable that both on-board and wrist worn chronographs were (and continue to be) indispensable to pilots. To a degree, having to “prove up” this point feels a bit like describing the color blue - almost so fundamental as to become difficult to know best how to “explain.”

Accordingly, the few excerpts below (together with those from other posts to date), I found to be merely exemplary in their content, period, and - importantly - still yet good reads for anyone

not needing convincing.

Collectively the materials to date addressing whether chronographs, including wrist chronographs, were useful to pilots should put that separate discussion to bed enough for present purposes. That way, later, we can move past that assumption and zoom into the lower level questions about how certain watch designs may or may not have aided (or been marketed to aid) such pilot’s needs.

Up first is the 1946 long form article specifically addressing the broad relationship of pilots to their clocks, with a bonus topical Universal Geneve add on the last page (marketing its utility to pilots).

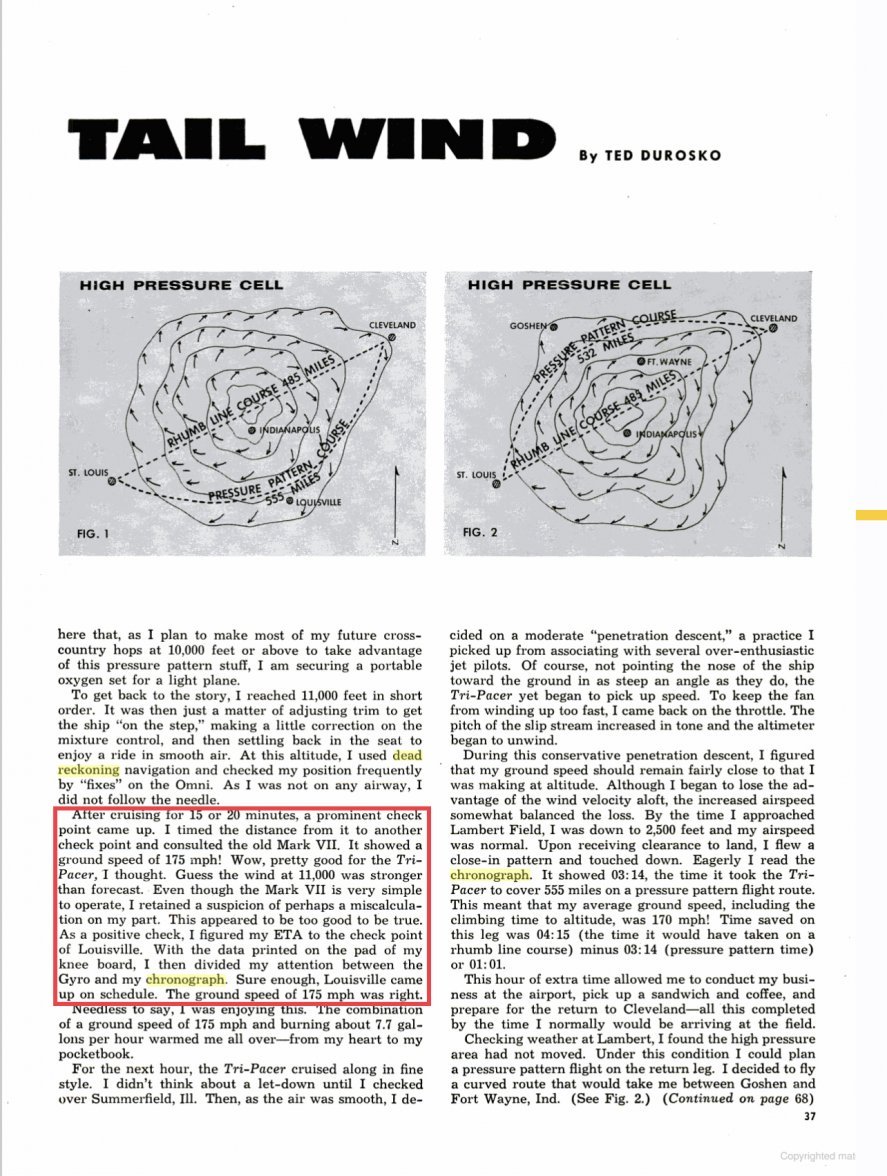

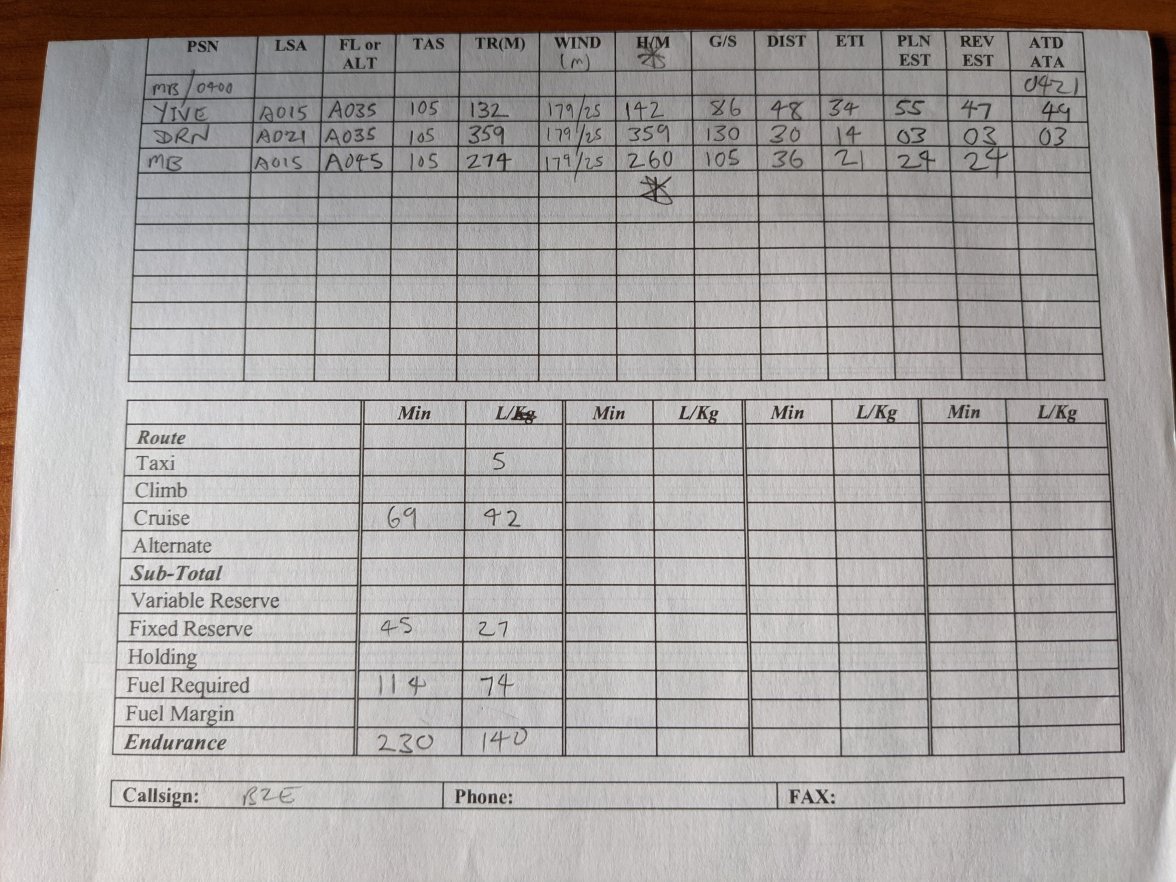

Next up is a 1955 article that is focused on the utilization of certain flying techniques to achieve altitudes and speeds and low fuel burn rates; the author was so surprised by the success of his methods to achieve speed, as told by his more sophisticated instrument panels, he goes to his chronograph to (in effect) manually check his ground speed and is pleased to find both methods agree.

(Note also that this is an instance of a pilot using the rule of 3/6 as a method to determine ground speed despite the existence of an on-board speedometer and equipment that accounts for ground speed - so the equation of [distance = speed X time] can be manipulated to solve for either ground distance or ground speed, depending on the pilot’s needs.)

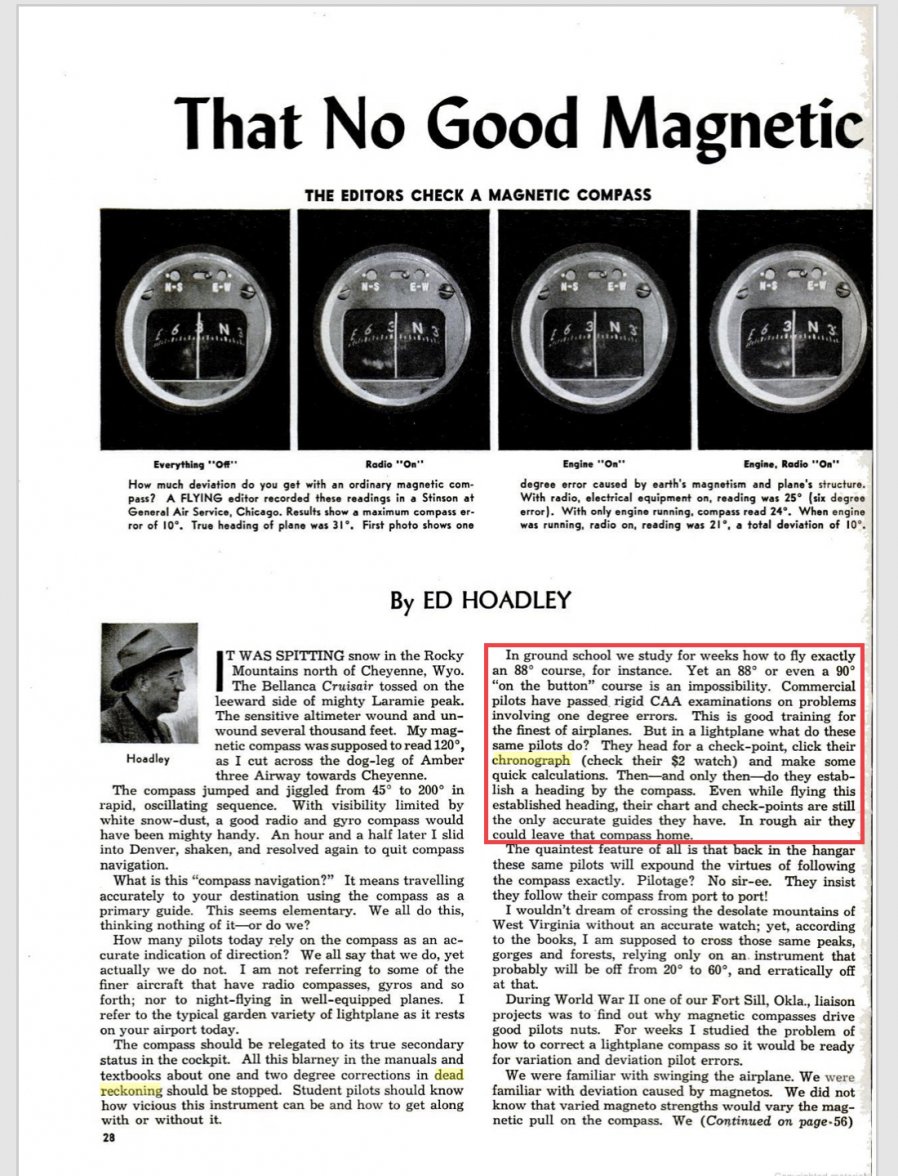

Next up is an article from 1951, wherein the author is essentially arguing that even the compass is so unreliable (or unwieldy) in certain situations that

only the chronograph (a mere “$2 tool”!) is the reliable pilot’s tool.

(Note in this article only the recognition that most pilots of small craft, hobby, etc., are performing rough calculations constantly from their chronograph, essentially in short hand, as their baseline certainty for navigation.)

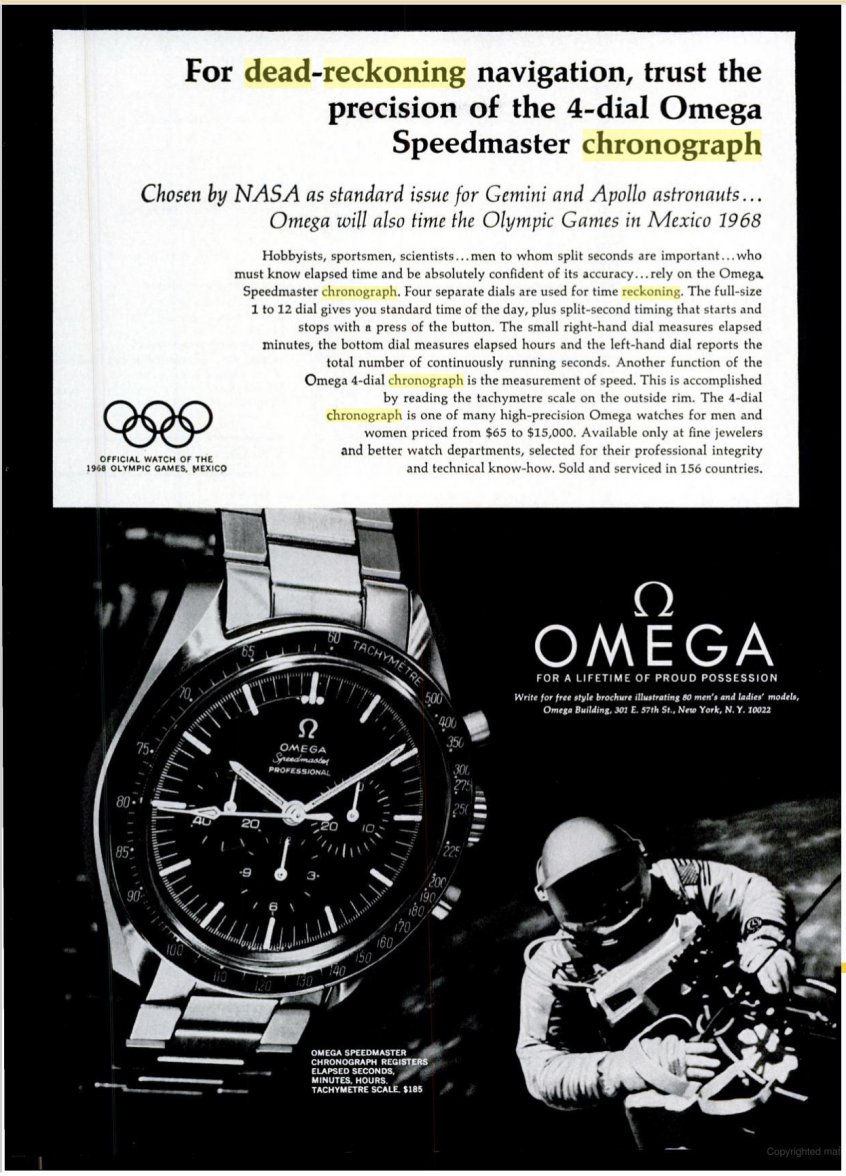

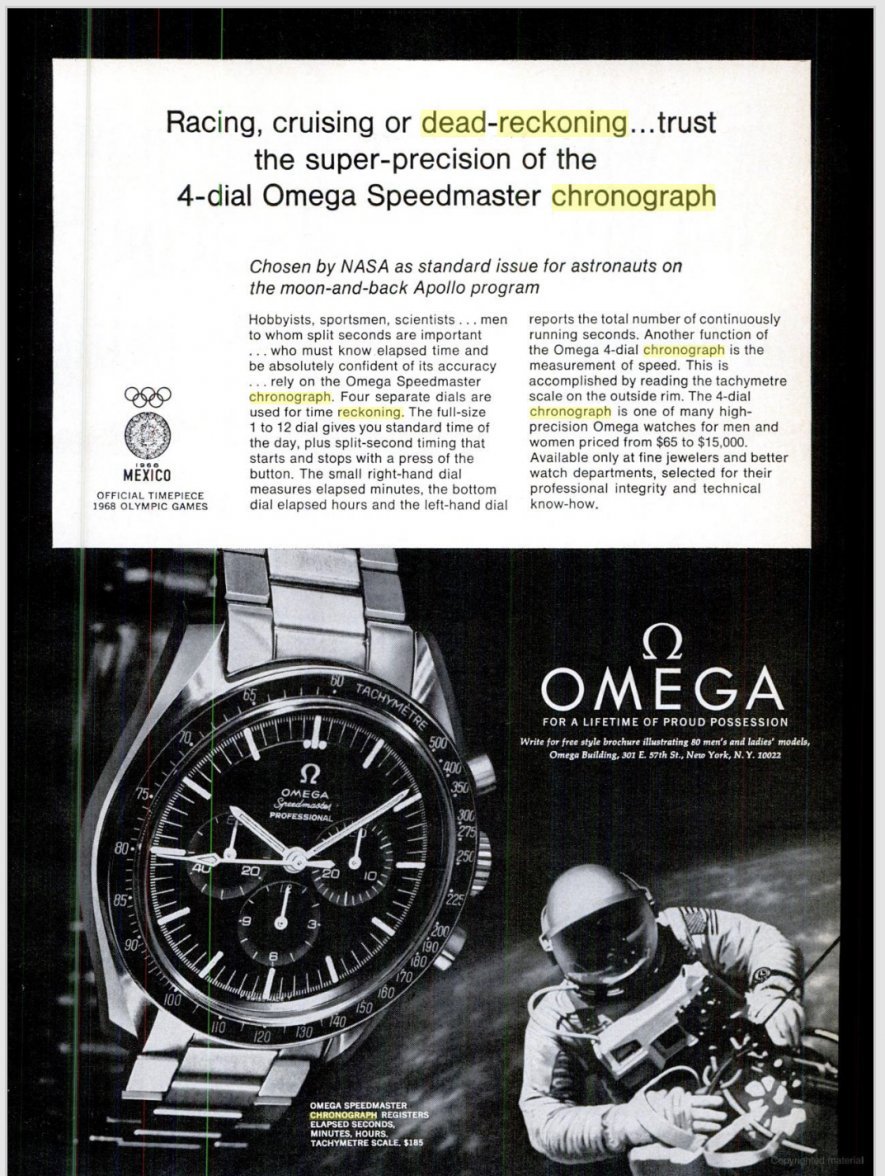

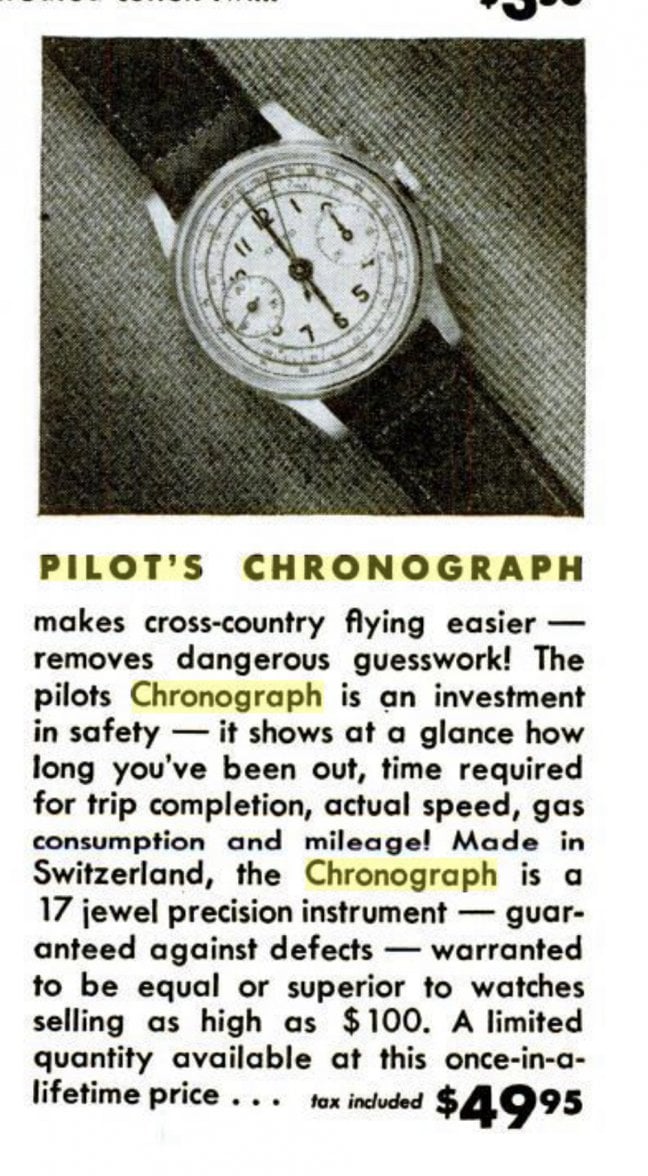

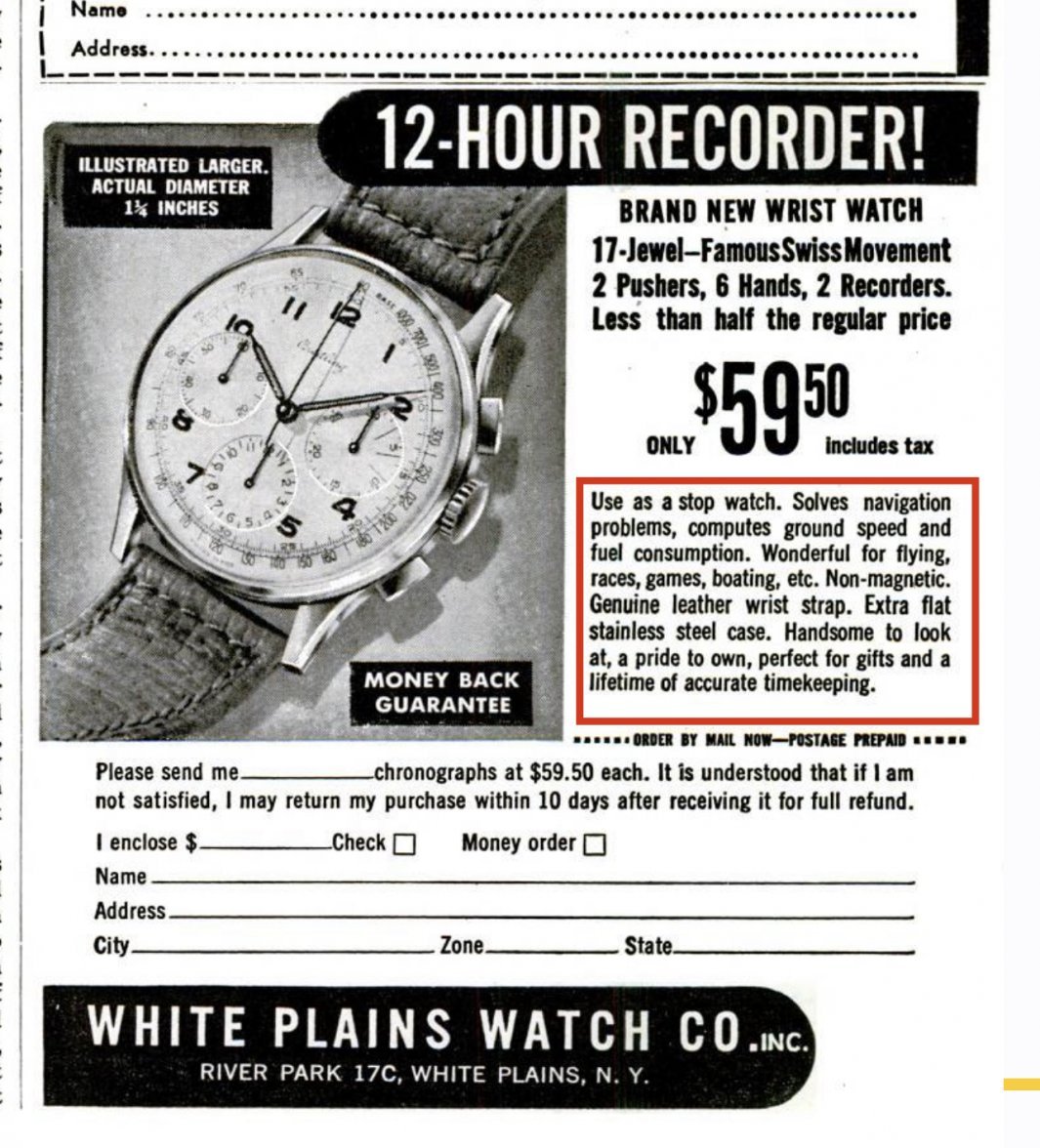

By the way, on the separate but related topic of whether manufacturers were marketing these utilities to pilots, the dozens (hundreds?) of period materials I’ve been through are saturated with evidence. For fun, below, I’m including just a few such example ads from the magazine editions excerpted above (aside from the UG add embedded above)