Braindrain

·The following is a bit of a write-up on the research made on my newest acquisition. I hope you enjoy the read.

Origins of Credor

Many folks have heard of, and know the origins of, Grand Seiko. Some even know about the related Grand Seiko / King Seiko (Daini/Suwa Seikosha) rivalry. However, a lesser number of collectors have heard of another of Seiko’s sub-brands, Credor. For those who are aware of Credor, it usually only means an awareness of the Eichi I and II. As a result, an even smaller subset of collectors knows about the origins of this JDM (Japan Domestic Market) Seiko sub-brand.

When Seiko started the Grand Seiko and Credor sub-brands, the goal was to create the “best” watch. However, although the goal sounded similar, just how exactly do these two sub-brands differ?

Grand Seiko was created in 1960 and evolved with 3 tenets in mind: accuracy, legibility, and durability. Grand Seiko was intended to be the culmination of the best, practical, everyday watch that can be easily read, counted upon for accurate timekeeping, and withstand daily wear. Other “rules” followed with Grand Seiko, such as the now-famous Taro Tanaka’s “Grammar of Design”, which is more than a whole other article unto itself.

Credor, on the other hand, was created in 1974. It’s logo represents three mountain peaks, with each peak touching a star. Originally branded as “Crêt d’Or” by Seiko, which literally means “golden peak”, it was later anglicized as Credor. The two names are pronounced exactly the same.

Source: plus9time

Similar to Grand Seiko, Credor models were developed to embrace the following 3 tenets: use of the latest technologies, use of precious metals, and highlight artisanal skills. The last tenet, artisanal skills, refers to activities such as ultra-thin movement assembly, engraving, decorations, and gem setting.

Early efforts from Credor solely focused on high-end quartz watches. While modern Credor has offered a few SS watches, “classical” Credor (for lack of a better term) only used precious metals. Although the name was created in 1974 as a sub-line within Seiko’s catalogue, Credor became it’s own brand in 1978 and the Credor logo first appeared in an 1980 catalogue.

Credor’s focus is to make the best dress watch, while Grand Seiko wants to make the best everyday watch. Along with that split in ideology are differences in design and intent.

Credor watches are unabashedly Japanese and are intended to reflect contemporary JP design. This may or may not align with Western designs, and may have influenced Seiko to keep Credor as a JDM-only brand. Another Credor hallmark is the focus on thin dress watches, with limited exceptions. Grand Seiko, in it’s ongoing refinement for better accuracy and robustness, just cannot have a thin dress watch in it’s line up as that would deviate from the Grand Seiko ethos. Credor, on the other hand, is not restrained by similar objectives and, additionally, is not bound by design rules (such as the Grammar of Design). As a result, Credor favours thinness over accuracy and robustness, but it’s catalogue has a far more diverse choice of styles than Grand Seiko.

Additionally, Credor watches are intended as luxury items, as a thin dress watch is meant to be. Some Credor watches are even adorned with jewels. This is one sandbox that Grand Seiko just does not play in.

Credor’s pursuit of thin dress watches, technology, and luxury led it onto the path of the next topic….

Rebirth of mechanical watchmaking at Seiko

The origins of how and who (in Seiko) led the mechanical movement renaissance are a bit fuzzy. Seiyajapan translated a flyer (from Seiko) which suggested a young engineer from Seiko, Jun Tanaka, visited Baselword in 1988 and noted the proliferation of mechanical watches, in the midst of the quartz crisis. Tanaka-san seemed to gain an understanding and an appreciation of the significance and longevity of mechanicals after that trip. Two years later, Seiko was seeking something special for it’s 110th year anniversary. Building upon his experience at Baselworld, Tanaka-san proposed the idea of a high end mechanical dress watch, which was subsequently accepted. Tanaka-san’s team re- created Cal 6810 and successfully sold 110 pieces of the "110th Aniv. U.T.D. 6810-6000 SCQL002".

Source: Credor

However, it is also worth noting, from KIH’s personal account of his interaction with Mr. Mamoru Sakurada (referenced below), KIH suggests Sakurada-san took leadership and initiative to revive the production of mechanical movements at Seiko (around 1990) and has been responsible for the Cal 68 series ever since.

The truth probably lies somewhere in the middle.

Artisanal nature of the Credor Cal 68XX

On the Cal. 68 series of movements, the Seiko website states “Due to its thinness of 1.98 mm, highly skilled watchmakers consistently handle everything from assembly and adjustment to casing. Accuracy in units of 1/100 mm is required for correcting the shape of each part and adjusting the clearance (the gaps required between parts), so the final finishing is done only by the watchmaker's sense of touch. The 68 series movement is a small-lot production movement that can be assembled by just one or two skilled watchmakers per day. It is a movement that makes even watchmakers say, ‘No matter how many years you've been doing it, you'll find it difficult to adjust the agave, ankle, and whiskers. This is truly a handmade watch.’ ”

While there may be some PR unicorn magic in that statement, a first-hand account from KIH (@puristspro) about his meeting with Master watchmaker, Mr. Mamoru Sakurada, seems to lend some credence to Seiko’s statement. KIH mentions that Sakurada-san, a watchmaker of 45 years (at the time of writing) and who joined Seiko in 1965, had been honored with the title of “Contemporary Master Craftsmen” of Japan, and also awarded the “Yellow Ribbon Medal” from the government (presented by the Emperor). I suspect the context of “Contemporary Master Craftsmen” is a government designation given to various master craftspeople around Japan, based on my knowledge of Japanese pottery. A BBC article seems to confirm my suspicion: “Because of the fragility of the craft knowledge being handed down, Japan has created a system of nationally recognised master artisans, and designated some of the best people working in each category ‘living national treasures’, to encourage esteem for – and the continuation of – work in these areas.”

Sakurada-san worked out of Seiko’s Shizukuishi Watch Studio in Morioka, Iwate prefecture, and was one of the watchmakers tasked with assembling and adjusting the Ultra Thin 68XX series movement. KIH mentions that, during their meeting, Sakurada-san was demonstrating the assembly of the Cal 6899 skeletonized movement.

A few excerpts of KIH’s post are noted below, with an emphasis on how Sakurada-san needed to constantly play and adjust the various parts of the movement, by hand:

KIH: He demonstrated the assembly of this ultra thin movement. At the beginning, I was told that although the number of the parts is about 120 and less than average mechanical movements out there, this movement won’t work by “just” assembling. It requires lots of manual adjustment in the process of assembly, thus requires proficiency and experience.

KIH: BUT, this is in reality the first tricky part. This bridge is rarely or never completely flat – due to many factors including the engraving process. For the wheels to rotate smoothly and keep the movement thin, the tolerance of the “error” is 1/100mm to 3/100mm. The master first checks the actual gap or play of the wheel and the bridge/ ruby. His fingers feel and “measure” whether it is within 3/100mm.

KIH: And if NOT, then he has to tighten or untighten the bushing around the ruby from either side by tiny amount to adjust. For normal watch, the tolerance is more than 5/100mm and bridge and wheels should fit instantly, but this is so thin it doesn't work that way.

He also has to check the flatness of this thin bridge because by the time it reaches him, a lot have already been done to it – cut and shave, bushing pushed in, and particularly for this 6899, the engraving. He checks the flatness by holding one side on the flat metal stand and press another side tip, and he “knows” how much it is up or down. Then he, by hand, with very sensitive touch, bends or unbend the part. That is only done by experience.

KIH: Put the smooth balance wheel mechanism in. Before this parts arrives here, the balance must be manually adjusted. How? This is the next tricky part. The smooth balance wheel is adjusted by putting the hole or holes in or shaving the surface of the rim of the wheel. He finds out where to shave or put the hole by measuring which position generates substantial delay (delay means “heavy”). He measure the movement with various positions and disassemble until the balance is right. It obviously takes a long time to really make this movement ready for casing.

Evolution of Credor Cal 68XX movements

The base of the Seiko/Credor 68XX movements lies with Cal 68A, introduced by Seiko in 1969. While movements from Seiko previous to Cal 68A generally focused on accuracy improvements, Cal 68A took a different turn and was meant to be fitted for ultra-thin dress watches. In 1973, Seiko introduced Cal 6810, which was kept in production almost a decade. While watches equipped with Cal 6810 were considered high-end for Seiko and priced at more than 4 times comparable King Seiko and Lord Marvel watches at the time, the onslaught of the quartz revolution forced Seiko to retire the Cal 6810 around 1978, in favour of using the Cal 7820 quartz movements.

As mentioned above, Seiko re-created the Cal 6810 in 1990, which was used in the "110th Aniv. U.T.D. 6810-6000 SCQL002".

Continued Evolution of Cal 68XX

After the success of the 110th Anniversary U.T.D. watch, Cal 6870 was created in 1993 as the Credor variant of the Cal 6810. In continuing with the architecture of Cal 6810, this “new” ultra-thin manual winding movement was intended to compete with Swiss competitors such as Piaget, Frederic Piguet, and JLC. Of note, Cal 6870 measures 1.98mm thick (not counting the cannon pinion and hour wheel) and had embellishments like anglage and cap jewels on the escape, third, and fourth wheels. Piaget’s ultra thin 9P movement (at the time) measures 2.0 mm thick. As a comparison, the legendary Frederic Piguet Cal 21 measures 1.75 mm thick.

Source: Credor

The Cal 68XX family further evolved with the Cal 6898 in 1996, which was a complete re-design from Cal 6870. Subsequent Cal 68XX movements developed after Cal 6898 followed the re-design, rather than the original Cal 6810 architecture.

The Cal 68XX family is assembled at Seiko's Shizukuishi Watch Studio in Morioka, Iwate prefecture, along with other high-end Seiko movements. Cal 6870 is still used by Credor today.

Technical specs of Cal 6810/6870

Cals 6810 and 6870 measure 19.77 mm by 16.9 mm, and as noted earlier, measure 1.98 mm thick. These movements use a standard 17 jewel arrangement, with an extra 5 diafix cap jewels to reduce friction – making a total count of 22 jewels. Not included in that count are four more jewels arranged on the plate under the barrel, which act as a glide for the mainspring (exposed to the base plate due to an open-sided barrel). This design allowed Seiko to reduce overall thickness.

Credor GBAQ996

My watch, the GBAQ996, succeeded the 110th Aniv. U.T.D. 6810-6000 SCQL002 (“UTD”). Unlike the UTD, which uses Cal 6810, the GBAQ996 uses the Credor Cal 6870 movement. Several other variants of this watch exist, such as WG (GBAQ993), YG with a black dial (GBAQ992), and YG with a white dial (GBAQ99?). The watch itself measures 30.0 x 21.0 mm (excluding crown) with a thickness of 5.5 mm.

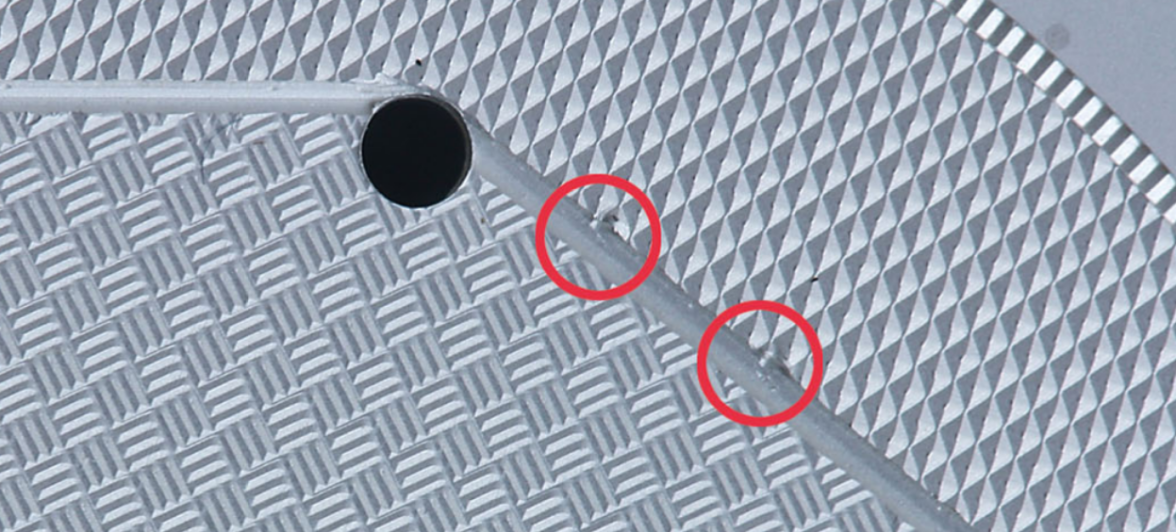

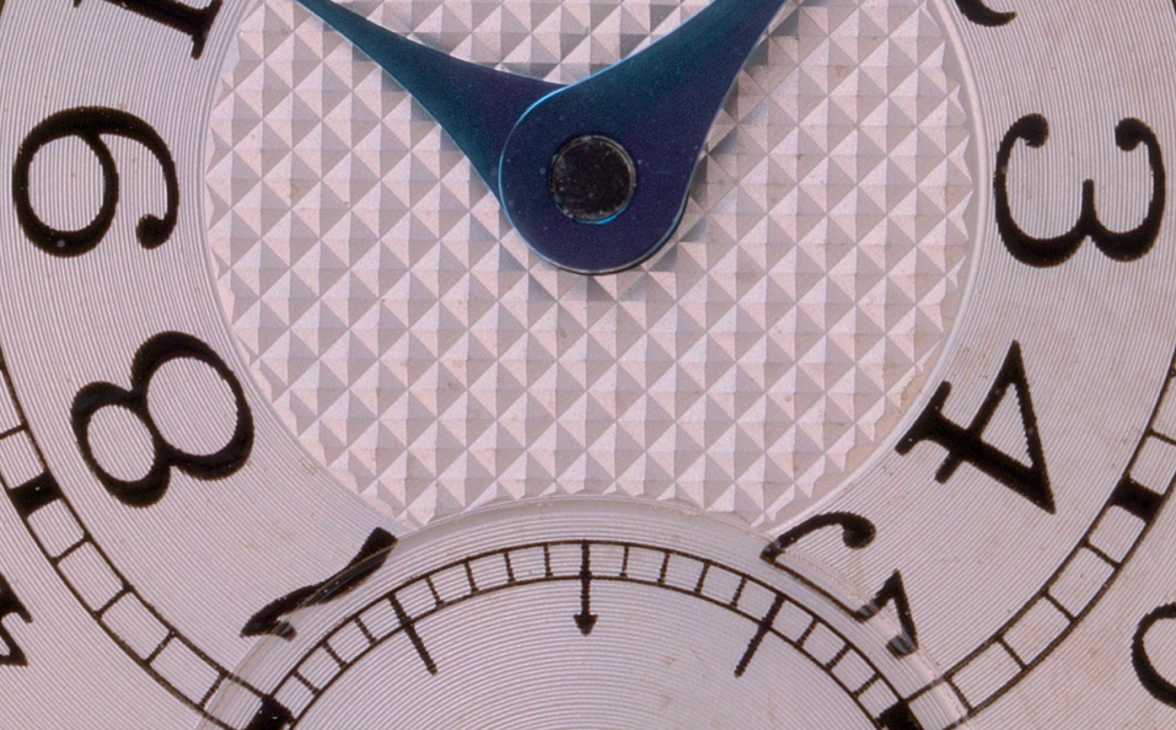

The dial is fairly sophisticated. The applied Credor logo sits on top, with Credor and Seiko branding just below. Providing a visual balance is the notation of “22 jewels” at the 6 o’clock position. The center portion of the dial is adorned with a clous de paris guilloché pattern, enclosed with railroad track minute markers. Looking at it from a 10x loupe, it seems to be hand guilloché, as the edges of the guilloché are smooth rather than sharp, added with the characteristic tiny imperfections that could only been seen when examining a 100% crop of my macro pics. The applied Credor logo acts as the 12 o’clock marker, with applied diamond/pyramidal shaped markers at 3, 6, and 9 positions, and painted stick markers for the other hours. Dauphine watch hands are used to indicate the hours and minutes. The watch is devoid of a seconds hand, adhering to “pure” dress watch design conventions.

The watch came with the original YG buckle and, surprisingly, the original strap. The underside of the strap has Credor branding, which is something I haven’t seen with other Seiko watches.

The Credor case clearly took inspiration from Art Deco watches from the 1920s and 30s. For example, here is a Longines Art Deco watch dating to approximately 1929. The Credor case borrows from this design, but adds additional elements and complexity.

Source: Curious Curio

In my opinion, Credor’s intricate YG tank-shaped case matches the sophisticated dial. The case has beautifully curved beveling on multiple surfaces that, as I understand it, significantly increases the difficulty and complexity of crafting. There is a tangible “step” outlining transition from the top/bottom of the case to the curved bevels/lugs. Looking at the watch from the dial, the lugs gently flare outwards thus providing more visual appeal. The side view shows that the lugs also slope downwards and extend beyond the caseback. The crown is adorned with a prominent Credor logo.

NB. This picture accentuates the intricate case construction. The sides are beveled as well as the “main” rectangular case.

NB. Note the gradual downward slope of the side that increases with the distance from the center of the case.

Lastly, I didn’t open the case back for fear of scratching up the case, so I dug around the internet for some examples. As noted, the Credor Cal 6870 is pretty much the same as the Seiko Cal 6810. As I was unable to open my caseback, I cannot opine whether the anglage was hand-finished, or not. The bridges are adorned with Tokyo Stripes. Why not Geneva stripes? Per the Seiko (Grand Seiko) website on Tokyo Stripes, “(the movement houses) multiple layers of the gears, bridge and barrel which echo the ridges of the beautiful mountain range of Shinshu that dominates the skyline.” If you use your imagination and orient the movement in your mind in such a way that, if you align the stripes on the bridge (covering the 3rd and 4th wheels) horizontally, you can see the mountain-shaped bridge resembling the Shinshu mountain range.

Source: Yahoo Auctions

Source: Epson Shinshu Artisan Watch Studio

Source: Overlay of Shinshu mountains with the Credor bridge

A special note is the motif of the Japanese flag on the inner case back, denoting the case was made in Japan.

Source: Yahoo Auctions

For many years, I was looking for a Reverso, without actually wanting to buy a Reverso. While the Reverso is an iconic watch and kudos are given to anyone who owns one, I was looking for something a bit more esoteric. Alternatives came up in my head, such as the Cartier Basculante and multiple iterations of the Tank, as well as vintage tonneau/tank pieces from the 40s. I even briefly considered a 1940s JLC triple date calendar with a seldom seen French-made YG multi-stepped case and a vintage Reverso pre-dating the 1937 (dial) merger between LeCoultre and Jaeger.

As luck would have it, a friend of mine alerted me to this Credor, as he was in the process of seriously considering the watch for purchase. After a bit of back and forth, he pulled the trigger. I happened to see it shortly after it arrived and was mesmerized. Although I had resigned myself to admire it from afar, that was perfectly fine with me. Fast forward a few months and, through a series of unforeseen and unscripted acquisitions, he decided to enact a “one in, out policy” and I was offered the watch.

While the encouraging trend these days is for smaller watches, I still often see new releases in the 38 - 41 mm diameter case sizes. Often, with lugs, these watches are just too big for my wrists. For me, the svelte size of the GBAQ996 is a perfect under-the-radar dress watch that exudes class and refinement. As a further bonus, it’s a great conversation starter with other watch enthusiasts - but only if they’re really into nerding out on watches.

Lastly, do I have any gripes with the watch? I love classically styled watches, both in case and dial design. I am not a fan of modern dials, with 7 lines (or more) of text + logo. That’s probably why I’m also a huge fan of military issued watches. Those watches were designed to be devoid of all but the absolutely necessary but minimum information.

So, what’s my gripe? As a counter-point and visual balance to the Seiko/Credor branding, the Credor GBAQ99X watches state “22 jewels” on the dial. Normally, any modern watch with that kind of writing is automatically disqualified from my collection. In this instance, however, it’s acceptable as it signifies Seiko’s/Credor’s return to mechanicals and is a nod to other enthusiasts that this is not a Credor with a quartz module.

I hope you enjoyed my little journey into the history of Credor and my watch. As always, much of the information has been researched already, and sources (below) are noted.

Sources

credor.com/crafts/movement

shizukuishi-watch.com/eng/challenge.html

seiyajapan.com/blogs/news/17933513-a-way-to-rebirth-of-seiko-s-mechanical-watches-vol-1

watch-wiki.net/doku.php?id=seiko_6800

ikigai-watches.com/grand-seiko-and-credor-the-two-faces-of-the-same-coin/

plus9time.com/blog/2018/10/22/credor-brand-introduction-and-history

watchprosite.com/?page=wf.forumpost&q=&fi=17&ti=702888&pi=4547558

bbc.com/culture/article/20210421-the-gentle-crafts-that-bring-peace

Origins of Credor

Many folks have heard of, and know the origins of, Grand Seiko. Some even know about the related Grand Seiko / King Seiko (Daini/Suwa Seikosha) rivalry. However, a lesser number of collectors have heard of another of Seiko’s sub-brands, Credor. For those who are aware of Credor, it usually only means an awareness of the Eichi I and II. As a result, an even smaller subset of collectors knows about the origins of this JDM (Japan Domestic Market) Seiko sub-brand.

When Seiko started the Grand Seiko and Credor sub-brands, the goal was to create the “best” watch. However, although the goal sounded similar, just how exactly do these two sub-brands differ?

Grand Seiko was created in 1960 and evolved with 3 tenets in mind: accuracy, legibility, and durability. Grand Seiko was intended to be the culmination of the best, practical, everyday watch that can be easily read, counted upon for accurate timekeeping, and withstand daily wear. Other “rules” followed with Grand Seiko, such as the now-famous Taro Tanaka’s “Grammar of Design”, which is more than a whole other article unto itself.

Credor, on the other hand, was created in 1974. It’s logo represents three mountain peaks, with each peak touching a star. Originally branded as “Crêt d’Or” by Seiko, which literally means “golden peak”, it was later anglicized as Credor. The two names are pronounced exactly the same.

Source: plus9time

Similar to Grand Seiko, Credor models were developed to embrace the following 3 tenets: use of the latest technologies, use of precious metals, and highlight artisanal skills. The last tenet, artisanal skills, refers to activities such as ultra-thin movement assembly, engraving, decorations, and gem setting.

Early efforts from Credor solely focused on high-end quartz watches. While modern Credor has offered a few SS watches, “classical” Credor (for lack of a better term) only used precious metals. Although the name was created in 1974 as a sub-line within Seiko’s catalogue, Credor became it’s own brand in 1978 and the Credor logo first appeared in an 1980 catalogue.

Credor’s focus is to make the best dress watch, while Grand Seiko wants to make the best everyday watch. Along with that split in ideology are differences in design and intent.

Credor watches are unabashedly Japanese and are intended to reflect contemporary JP design. This may or may not align with Western designs, and may have influenced Seiko to keep Credor as a JDM-only brand. Another Credor hallmark is the focus on thin dress watches, with limited exceptions. Grand Seiko, in it’s ongoing refinement for better accuracy and robustness, just cannot have a thin dress watch in it’s line up as that would deviate from the Grand Seiko ethos. Credor, on the other hand, is not restrained by similar objectives and, additionally, is not bound by design rules (such as the Grammar of Design). As a result, Credor favours thinness over accuracy and robustness, but it’s catalogue has a far more diverse choice of styles than Grand Seiko.

Additionally, Credor watches are intended as luxury items, as a thin dress watch is meant to be. Some Credor watches are even adorned with jewels. This is one sandbox that Grand Seiko just does not play in.

Credor’s pursuit of thin dress watches, technology, and luxury led it onto the path of the next topic….

Rebirth of mechanical watchmaking at Seiko

The origins of how and who (in Seiko) led the mechanical movement renaissance are a bit fuzzy. Seiyajapan translated a flyer (from Seiko) which suggested a young engineer from Seiko, Jun Tanaka, visited Baselword in 1988 and noted the proliferation of mechanical watches, in the midst of the quartz crisis. Tanaka-san seemed to gain an understanding and an appreciation of the significance and longevity of mechanicals after that trip. Two years later, Seiko was seeking something special for it’s 110th year anniversary. Building upon his experience at Baselworld, Tanaka-san proposed the idea of a high end mechanical dress watch, which was subsequently accepted. Tanaka-san’s team re- created Cal 6810 and successfully sold 110 pieces of the "110th Aniv. U.T.D. 6810-6000 SCQL002".

Source: Credor

However, it is also worth noting, from KIH’s personal account of his interaction with Mr. Mamoru Sakurada (referenced below), KIH suggests Sakurada-san took leadership and initiative to revive the production of mechanical movements at Seiko (around 1990) and has been responsible for the Cal 68 series ever since.

The truth probably lies somewhere in the middle.

Artisanal nature of the Credor Cal 68XX

On the Cal. 68 series of movements, the Seiko website states “Due to its thinness of 1.98 mm, highly skilled watchmakers consistently handle everything from assembly and adjustment to casing. Accuracy in units of 1/100 mm is required for correcting the shape of each part and adjusting the clearance (the gaps required between parts), so the final finishing is done only by the watchmaker's sense of touch. The 68 series movement is a small-lot production movement that can be assembled by just one or two skilled watchmakers per day. It is a movement that makes even watchmakers say, ‘No matter how many years you've been doing it, you'll find it difficult to adjust the agave, ankle, and whiskers. This is truly a handmade watch.’ ”

While there may be some PR unicorn magic in that statement, a first-hand account from KIH (@puristspro) about his meeting with Master watchmaker, Mr. Mamoru Sakurada, seems to lend some credence to Seiko’s statement. KIH mentions that Sakurada-san, a watchmaker of 45 years (at the time of writing) and who joined Seiko in 1965, had been honored with the title of “Contemporary Master Craftsmen” of Japan, and also awarded the “Yellow Ribbon Medal” from the government (presented by the Emperor). I suspect the context of “Contemporary Master Craftsmen” is a government designation given to various master craftspeople around Japan, based on my knowledge of Japanese pottery. A BBC article seems to confirm my suspicion: “Because of the fragility of the craft knowledge being handed down, Japan has created a system of nationally recognised master artisans, and designated some of the best people working in each category ‘living national treasures’, to encourage esteem for – and the continuation of – work in these areas.”

Sakurada-san worked out of Seiko’s Shizukuishi Watch Studio in Morioka, Iwate prefecture, and was one of the watchmakers tasked with assembling and adjusting the Ultra Thin 68XX series movement. KIH mentions that, during their meeting, Sakurada-san was demonstrating the assembly of the Cal 6899 skeletonized movement.

A few excerpts of KIH’s post are noted below, with an emphasis on how Sakurada-san needed to constantly play and adjust the various parts of the movement, by hand:

KIH: He demonstrated the assembly of this ultra thin movement. At the beginning, I was told that although the number of the parts is about 120 and less than average mechanical movements out there, this movement won’t work by “just” assembling. It requires lots of manual adjustment in the process of assembly, thus requires proficiency and experience.

KIH: BUT, this is in reality the first tricky part. This bridge is rarely or never completely flat – due to many factors including the engraving process. For the wheels to rotate smoothly and keep the movement thin, the tolerance of the “error” is 1/100mm to 3/100mm. The master first checks the actual gap or play of the wheel and the bridge/ ruby. His fingers feel and “measure” whether it is within 3/100mm.

KIH: And if NOT, then he has to tighten or untighten the bushing around the ruby from either side by tiny amount to adjust. For normal watch, the tolerance is more than 5/100mm and bridge and wheels should fit instantly, but this is so thin it doesn't work that way.

He also has to check the flatness of this thin bridge because by the time it reaches him, a lot have already been done to it – cut and shave, bushing pushed in, and particularly for this 6899, the engraving. He checks the flatness by holding one side on the flat metal stand and press another side tip, and he “knows” how much it is up or down. Then he, by hand, with very sensitive touch, bends or unbend the part. That is only done by experience.

KIH: Put the smooth balance wheel mechanism in. Before this parts arrives here, the balance must be manually adjusted. How? This is the next tricky part. The smooth balance wheel is adjusted by putting the hole or holes in or shaving the surface of the rim of the wheel. He finds out where to shave or put the hole by measuring which position generates substantial delay (delay means “heavy”). He measure the movement with various positions and disassemble until the balance is right. It obviously takes a long time to really make this movement ready for casing.

Evolution of Credor Cal 68XX movements

The base of the Seiko/Credor 68XX movements lies with Cal 68A, introduced by Seiko in 1969. While movements from Seiko previous to Cal 68A generally focused on accuracy improvements, Cal 68A took a different turn and was meant to be fitted for ultra-thin dress watches. In 1973, Seiko introduced Cal 6810, which was kept in production almost a decade. While watches equipped with Cal 6810 were considered high-end for Seiko and priced at more than 4 times comparable King Seiko and Lord Marvel watches at the time, the onslaught of the quartz revolution forced Seiko to retire the Cal 6810 around 1978, in favour of using the Cal 7820 quartz movements.

As mentioned above, Seiko re-created the Cal 6810 in 1990, which was used in the "110th Aniv. U.T.D. 6810-6000 SCQL002".

Continued Evolution of Cal 68XX

After the success of the 110th Anniversary U.T.D. watch, Cal 6870 was created in 1993 as the Credor variant of the Cal 6810. In continuing with the architecture of Cal 6810, this “new” ultra-thin manual winding movement was intended to compete with Swiss competitors such as Piaget, Frederic Piguet, and JLC. Of note, Cal 6870 measures 1.98mm thick (not counting the cannon pinion and hour wheel) and had embellishments like anglage and cap jewels on the escape, third, and fourth wheels. Piaget’s ultra thin 9P movement (at the time) measures 2.0 mm thick. As a comparison, the legendary Frederic Piguet Cal 21 measures 1.75 mm thick.

Source: Credor

The Cal 68XX family further evolved with the Cal 6898 in 1996, which was a complete re-design from Cal 6870. Subsequent Cal 68XX movements developed after Cal 6898 followed the re-design, rather than the original Cal 6810 architecture.

The Cal 68XX family is assembled at Seiko's Shizukuishi Watch Studio in Morioka, Iwate prefecture, along with other high-end Seiko movements. Cal 6870 is still used by Credor today.

Technical specs of Cal 6810/6870

Cals 6810 and 6870 measure 19.77 mm by 16.9 mm, and as noted earlier, measure 1.98 mm thick. These movements use a standard 17 jewel arrangement, with an extra 5 diafix cap jewels to reduce friction – making a total count of 22 jewels. Not included in that count are four more jewels arranged on the plate under the barrel, which act as a glide for the mainspring (exposed to the base plate due to an open-sided barrel). This design allowed Seiko to reduce overall thickness.

Credor GBAQ996

My watch, the GBAQ996, succeeded the 110th Aniv. U.T.D. 6810-6000 SCQL002 (“UTD”). Unlike the UTD, which uses Cal 6810, the GBAQ996 uses the Credor Cal 6870 movement. Several other variants of this watch exist, such as WG (GBAQ993), YG with a black dial (GBAQ992), and YG with a white dial (GBAQ99?). The watch itself measures 30.0 x 21.0 mm (excluding crown) with a thickness of 5.5 mm.

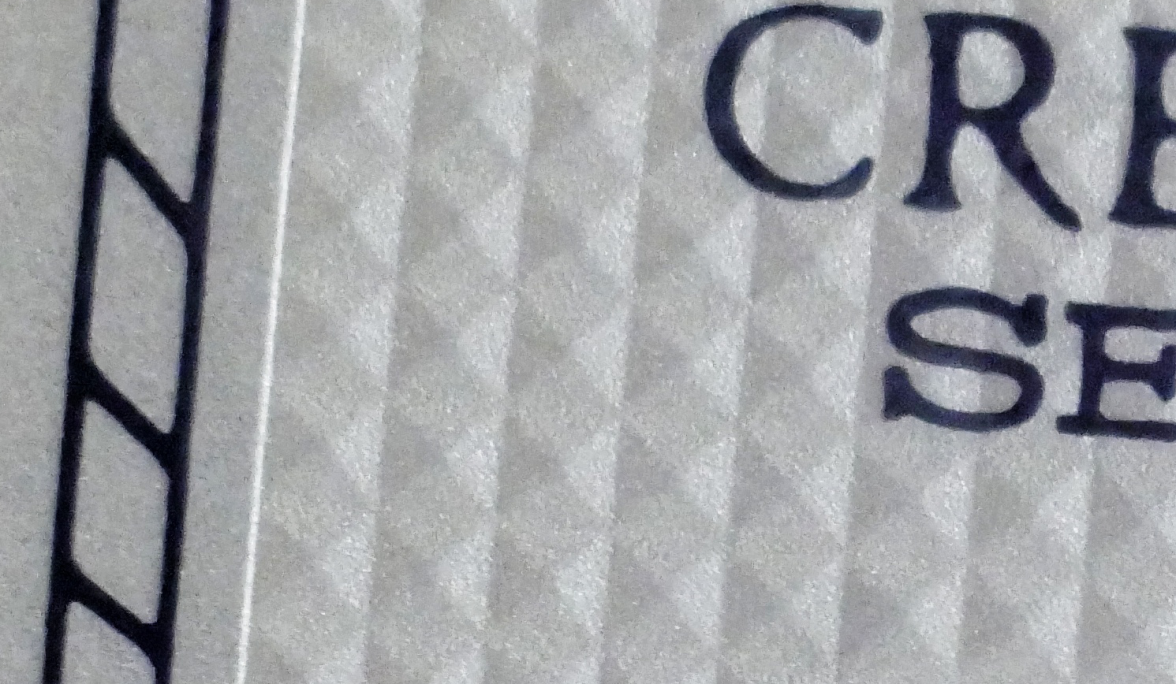

The dial is fairly sophisticated. The applied Credor logo sits on top, with Credor and Seiko branding just below. Providing a visual balance is the notation of “22 jewels” at the 6 o’clock position. The center portion of the dial is adorned with a clous de paris guilloché pattern, enclosed with railroad track minute markers. Looking at it from a 10x loupe, it seems to be hand guilloché, as the edges of the guilloché are smooth rather than sharp, added with the characteristic tiny imperfections that could only been seen when examining a 100% crop of my macro pics. The applied Credor logo acts as the 12 o’clock marker, with applied diamond/pyramidal shaped markers at 3, 6, and 9 positions, and painted stick markers for the other hours. Dauphine watch hands are used to indicate the hours and minutes. The watch is devoid of a seconds hand, adhering to “pure” dress watch design conventions.

The watch came with the original YG buckle and, surprisingly, the original strap. The underside of the strap has Credor branding, which is something I haven’t seen with other Seiko watches.

The Credor case clearly took inspiration from Art Deco watches from the 1920s and 30s. For example, here is a Longines Art Deco watch dating to approximately 1929. The Credor case borrows from this design, but adds additional elements and complexity.

Source: Curious Curio

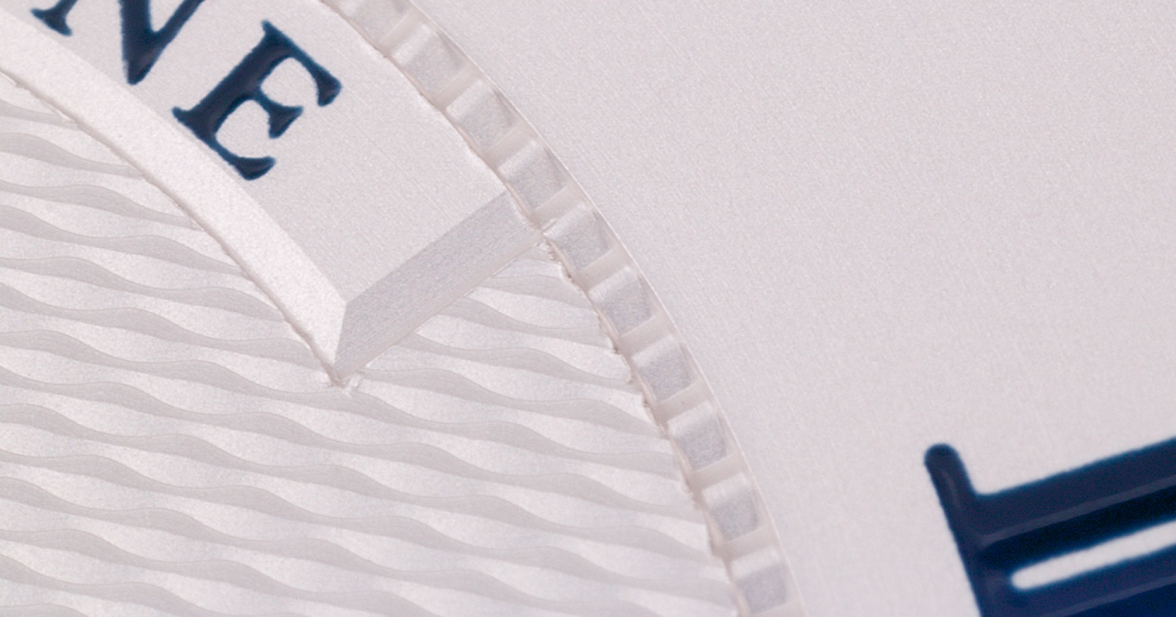

In my opinion, Credor’s intricate YG tank-shaped case matches the sophisticated dial. The case has beautifully curved beveling on multiple surfaces that, as I understand it, significantly increases the difficulty and complexity of crafting. There is a tangible “step” outlining transition from the top/bottom of the case to the curved bevels/lugs. Looking at the watch from the dial, the lugs gently flare outwards thus providing more visual appeal. The side view shows that the lugs also slope downwards and extend beyond the caseback. The crown is adorned with a prominent Credor logo.

NB. This picture accentuates the intricate case construction. The sides are beveled as well as the “main” rectangular case.

NB. Note the gradual downward slope of the side that increases with the distance from the center of the case.

Lastly, I didn’t open the case back for fear of scratching up the case, so I dug around the internet for some examples. As noted, the Credor Cal 6870 is pretty much the same as the Seiko Cal 6810. As I was unable to open my caseback, I cannot opine whether the anglage was hand-finished, or not. The bridges are adorned with Tokyo Stripes. Why not Geneva stripes? Per the Seiko (Grand Seiko) website on Tokyo Stripes, “(the movement houses) multiple layers of the gears, bridge and barrel which echo the ridges of the beautiful mountain range of Shinshu that dominates the skyline.” If you use your imagination and orient the movement in your mind in such a way that, if you align the stripes on the bridge (covering the 3rd and 4th wheels) horizontally, you can see the mountain-shaped bridge resembling the Shinshu mountain range.

Source: Yahoo Auctions

Source: Epson Shinshu Artisan Watch Studio

Source: Overlay of Shinshu mountains with the Credor bridge

A special note is the motif of the Japanese flag on the inner case back, denoting the case was made in Japan.

Source: Yahoo Auctions

For many years, I was looking for a Reverso, without actually wanting to buy a Reverso. While the Reverso is an iconic watch and kudos are given to anyone who owns one, I was looking for something a bit more esoteric. Alternatives came up in my head, such as the Cartier Basculante and multiple iterations of the Tank, as well as vintage tonneau/tank pieces from the 40s. I even briefly considered a 1940s JLC triple date calendar with a seldom seen French-made YG multi-stepped case and a vintage Reverso pre-dating the 1937 (dial) merger between LeCoultre and Jaeger.

As luck would have it, a friend of mine alerted me to this Credor, as he was in the process of seriously considering the watch for purchase. After a bit of back and forth, he pulled the trigger. I happened to see it shortly after it arrived and was mesmerized. Although I had resigned myself to admire it from afar, that was perfectly fine with me. Fast forward a few months and, through a series of unforeseen and unscripted acquisitions, he decided to enact a “one in, out policy” and I was offered the watch.

While the encouraging trend these days is for smaller watches, I still often see new releases in the 38 - 41 mm diameter case sizes. Often, with lugs, these watches are just too big for my wrists. For me, the svelte size of the GBAQ996 is a perfect under-the-radar dress watch that exudes class and refinement. As a further bonus, it’s a great conversation starter with other watch enthusiasts - but only if they’re really into nerding out on watches.

Lastly, do I have any gripes with the watch? I love classically styled watches, both in case and dial design. I am not a fan of modern dials, with 7 lines (or more) of text + logo. That’s probably why I’m also a huge fan of military issued watches. Those watches were designed to be devoid of all but the absolutely necessary but minimum information.

So, what’s my gripe? As a counter-point and visual balance to the Seiko/Credor branding, the Credor GBAQ99X watches state “22 jewels” on the dial. Normally, any modern watch with that kind of writing is automatically disqualified from my collection. In this instance, however, it’s acceptable as it signifies Seiko’s/Credor’s return to mechanicals and is a nod to other enthusiasts that this is not a Credor with a quartz module.

I hope you enjoyed my little journey into the history of Credor and my watch. As always, much of the information has been researched already, and sources (below) are noted.

Sources

credor.com/crafts/movement

shizukuishi-watch.com/eng/challenge.html

seiyajapan.com/blogs/news/17933513-a-way-to-rebirth-of-seiko-s-mechanical-watches-vol-1

watch-wiki.net/doku.php?id=seiko_6800

ikigai-watches.com/grand-seiko-and-credor-the-two-faces-of-the-same-coin/

plus9time.com/blog/2018/10/22/credor-brand-introduction-and-history

watchprosite.com/?page=wf.forumpost&q=&fi=17&ti=702888&pi=4547558

bbc.com/culture/article/20210421-the-gentle-crafts-that-bring-peace