sheepdoll

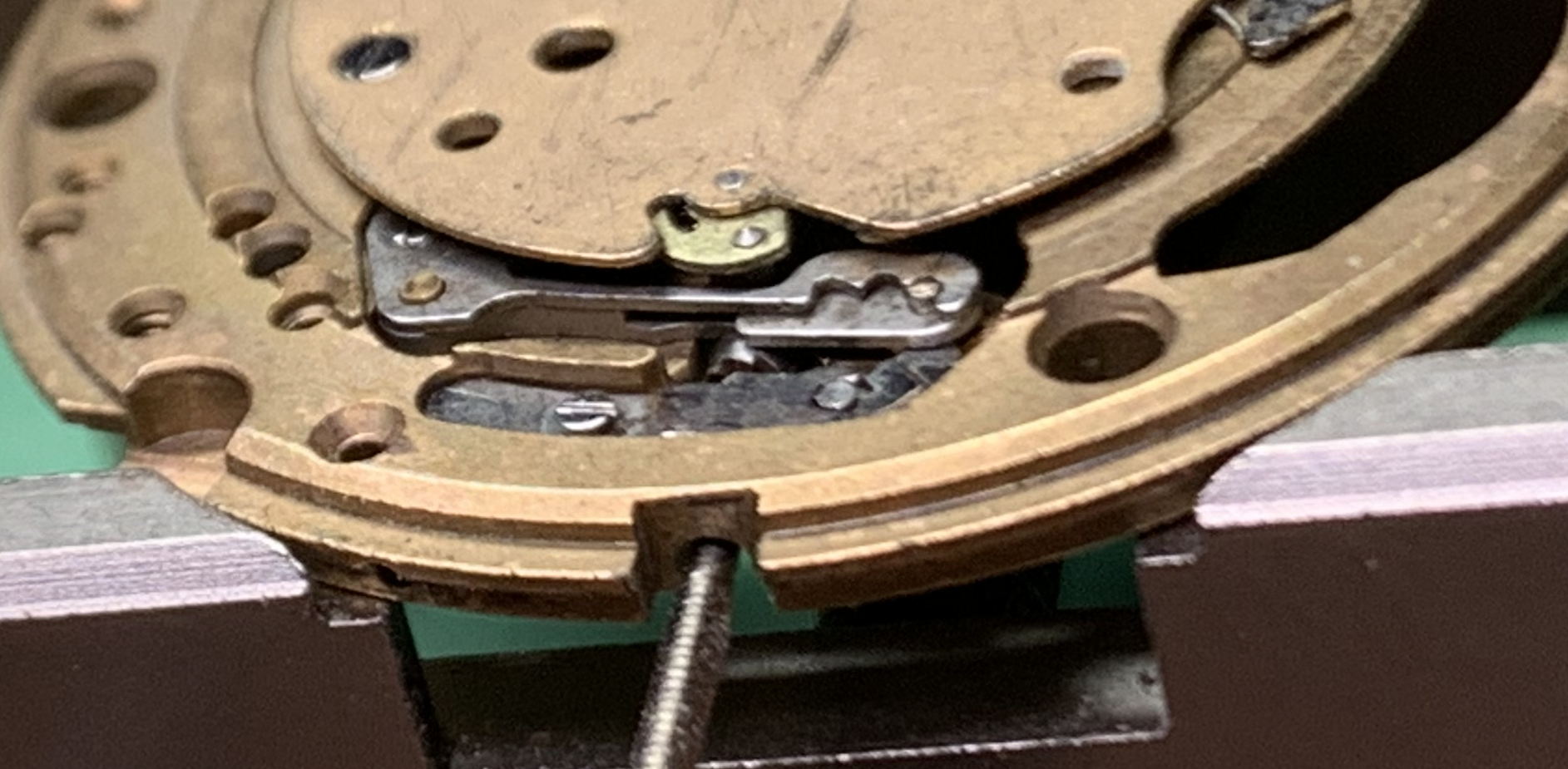

·So I finally got around to seeing if the fiber laser can make a watch part.

I used the USB microscope to photograph the part then trace it with a program called lightburn. This works much like Illustrator.

The parts are modeled on some quickset parts I got recently. One of them tends to sell for near 60. Surprisingly the more complex corrector sells for less than half of that. The prices though add up when one needs more than 3 of each.

Mostly the time was spent experimenting with different materials.

Surprisingly the steel cut better than the brass. I was using old razor blades and saw blades. The thickness is a bit much. The laser does not seem to want to cut through the last little bit. I think it welds it when the kerf gets two deep. I tried thinner metal, but ran too many passes and it warped.

Still the results are promising.

Does require a bit more hand finishing that I would like. I was mostly working with trial and error. Photographing the edge of the ruler really helped with the scaling.

I had assembled the parts back into the watch, so did not have them with me to check for thickness. Some guidelings suggest milling them off from the back. I was limited in time to try that step. The extra lines are used to make the parts break away from the stock. It is hard to remove the inside sprial on the corrector.

This is not a powerful laser. The beam locally heats the stock and causes warping. It would probably be a good idea to do additional heat treating to even the temper back out.

I have an old book called 21st century watchmaking which is about grinding similar type parts. This process is not that much different. What the laser would be good at is for the marking out of the parts.

These machines are becoming more accessible. So I suspect that more if this sort of thing will be seen in the future. Especially when relating to hands and dials. Will also make checking for originality more difficult.

Will be a step up from using a paperclip to replace a missing spring.

I used the USB microscope to photograph the part then trace it with a program called lightburn. This works much like Illustrator.

The parts are modeled on some quickset parts I got recently. One of them tends to sell for near 60. Surprisingly the more complex corrector sells for less than half of that. The prices though add up when one needs more than 3 of each.

Mostly the time was spent experimenting with different materials.

Surprisingly the steel cut better than the brass. I was using old razor blades and saw blades. The thickness is a bit much. The laser does not seem to want to cut through the last little bit. I think it welds it when the kerf gets two deep. I tried thinner metal, but ran too many passes and it warped.

Still the results are promising.

Does require a bit more hand finishing that I would like. I was mostly working with trial and error. Photographing the edge of the ruler really helped with the scaling.

I had assembled the parts back into the watch, so did not have them with me to check for thickness. Some guidelings suggest milling them off from the back. I was limited in time to try that step. The extra lines are used to make the parts break away from the stock. It is hard to remove the inside sprial on the corrector.

This is not a powerful laser. The beam locally heats the stock and causes warping. It would probably be a good idea to do additional heat treating to even the temper back out.

I have an old book called 21st century watchmaking which is about grinding similar type parts. This process is not that much different. What the laser would be good at is for the marking out of the parts.

These machines are becoming more accessible. So I suspect that more if this sort of thing will be seen in the future. Especially when relating to hands and dials. Will also make checking for originality more difficult.

Will be a step up from using a paperclip to replace a missing spring.