Horology 101: the 5 Most Influential Automatic Wristwatch Calibers

ClarendonVintage

·not very well read on movements, but is the GP gyromatic of any significance in terms of automatic movements?

- Posts

- 25,980

- Likes

- 27,692

ulackfocus

·is the GP gyromatic of any significance in terms of automatic movements?

GP had offered 18k bph and 21.6k bph Gyromatics since the late 1950's that weren't anything groundbreaking. Their caliber 32A was the first 36k bph caliber available to the public when offered in 1966. Unfortunately, Longines had been sending 36k bph calibers to the Neuchatel Observatory competitions since 1959 so that speed wasn't exactly new. A very nice movement, just not worthy of Top 5 recognition, particularly before the other honorable mentions already discussed in this thread.

AveConscientia

·There's no doubt that automatic winding units revolutionized the wristwatch. Several inventions, subsequent improvements, and even specific movements have had a vast influence on the industry. Take a look at the Valjoux 7750 series as a recent example - to say it's ubiquitous is an understatement! Regardless of how many watches are powered by a 7750, it didn't make the list because it didn't break new ground. The top 5 are in chronological order.

Harwood bumper

patented: 1924

This winding system may not have been the most efficient, but it was the first. It spawned similar systems in dozens of brands like Omega, Movado, and JLC. Still used into the 60's (in the JLC Memovox for example), they finally disappeared in the 70's.

Rolex Perpetual

patented: 1933

The list of companies that were influenced by this would be too long to type! It was the first 360˚ rotor wristwatch caliber and spawned a new direction in the industry. Combined with Rolex's trademark water resistant Oyster case, it formed the famous Oyster Perpetual.

IWC Pellaton

patented: 1946 & 1950

Seen as the simplest and most efficient winding system ever created, it is still in use today in the IWC 5000 and 8000 series calibers. While Longines did have a flirtation with a similar design in 1945, they added the Pellaton system to their manual winding 8.68N caliber to create the 19A series in 1952 - a very popular movement with the public. Seiko's Magic Lever winding system was based on the concept of IWC's Pellaton excenter technology. Cyma patented a double excenter winding unit even more efficient than IWC's in the early 50's (click HERE for more information from Dr Ranfft's website).

Eterna ball bearing

patented: 1948

Here's the first major improvement to the 360˚ rotor. It was introduced first into ladies watches, and installed in men's versions in 1950. As soon as other companies could get around patent infringement, they adopted & adapted this mechanism to their automatics. This system is still used by ETA who supplies the majority of the industry with movements.

Buren micro-rotor

patented: 1954

When introduced in 1957 inside their Super Slender series as the caliber 1000 and 1001, it was an immediate hit. There was a big push towards thinner watches in that era and this system met the call. Brands like Hamilton, Bulova, and even IWC licensed Buren's products for use in their own watches. Universal Geneve released a nearly identical movement and subsequently lost a patent infringement case to Buren which led to UG's paying of royalties. The Chronomatic Group* used a Buren micro-rotor caliber to make the first automatic chronograph available to the public in 1969. Many high end manufacturers have micro-rotor calibers today including Patek Philippe and Chopard.

Conspicuously absent from the list (and open for discussion) is the Zenith El Primero. While it was the first integrated self winding chronograph, it shared the spotlight with Seiko's 6139 and the Chronomatic Group's caliber 11 in 1969. It also was a combination of technologies. 36,000 bph calibers had been introduced to the public by Girard Perregaux in 1965 and were sent to the Neuchatel Observatory Chronometer Competition by Longines (the caliber 360) as early as 1959. While the EP is a fantastic movement, it did not change the industry as much as the other 5 on the list IMO. It isn't as influential as the Valjoux 7750 family either.

*The caliber 11 is also a worthy honorable mention since the Chronomatic Group team of Breitling, Hamilton, Buren, Heuer, and Dubois Dépraz was the first to rivet a chronograph module to an existing movement. They used a Buren micro-rotor caliber 1280 because of it's slim profile and piggy backed the Dubois Dépraz module on top - a practice still used today in a wide variety of watches but now usually attached to an ETA movement like the 2824 or 2892.

Thanks to Adam, Tony, Andy, Steve, Chin, and Tim for their help with pictures, suggestions, and data.

GuiltyBoomerang

·Seiko 6139?

@ulackfocus already mentioned that if there was a top 10, it would probably be in it...along with the El Primero, Bidynator, Cal 11, and Valjoux 7750.

AveConscientia

·@ulackfocus already mentioned that if there was a top 10, it would probably be in it...along with the El Primero, Bidynator, Cal 11, and Valjoux 7750.

JimInOz

··Melbourne AustraliaNot particularly major, but I think it's as just innovative as Eterna's bearings.

Taking the steps from a Harwood bumper, via a Rolex Perpetual (both of which only worked "half the time"), to a full two-way winding mechanism which increased the efficiency of the automatic rotor is in my view, worthy of recognition in this discussion.

Archer

··Omega Qualified WatchmakerNot particularly major, but I think it's as just innovative as Eterna's bearings.

Taking the steps from a Harwood bumper, via a Rolex Perpetual (both of which only worked "half the time"), to a full two-way winding mechanism which increased the efficiency of the automatic rotor is in my view, worthy of recognition in this discussion.

Thanks for the reply. For me personally this is an interesting topic and how people view it.

I can understand why it might seem obvious that winding in both directions instead of just "half the time" would lead to greater winding efficiency. But there's been a lot of research done to determine under what conditions that winding in both directions is actually "more efficient" and there's evidence that in some cases, winding in one direction only will put more turns on the barrel arbor over the course of a day. When winding in both directions some amount of angular displacement of the rotor is taken up with the winding mechanism switching directions - known as the dead angle where no winding occurs. Systems that wind in both directions tend to be more complex, have greater number of parts, and greater friction in the winding system also, leading to more weight needed to wind the same strength mainspring. So with winding in two directions, you don't double the amount of winding as might be assumed.

With the more sedentary lifestyle people lead today, with smaller wrist movements generally, single direction winding can be better than winding in both directions. With winding in both directions and small movements, often the rotor will just oscillate back and forth in the dead angle, and no winding occurs. So it's not as cut and dried as it may appear at first...this is why some companies still choose to use automatic systems that only wind in one direction. It's a topic that is maybe too far down the rabbit hole for most here, but winding in both directions is not always giving the best efficiency.

Certainly coming up with the engineering to enable winding in both directions is worthy of recognition though.

Cheers, Al

STANDY

··schizophrenic pizza orderer and watch collectorGP had offered 18k bph and 21.6k bph Gyromatics since the late 1950's that weren't anything groundbreaking. Their caliber 32A was the first 36k bph caliber available to the public when offered in 1966. Unfortunately, Longines had been sending 36k bph calibers to the Neuchatel Observatory competitions since 1959 so that speed wasn't exactly new. A very nice movement, just not worthy of Top 5 recognition, particularly before the other honorable mentions already discussed in this thread.

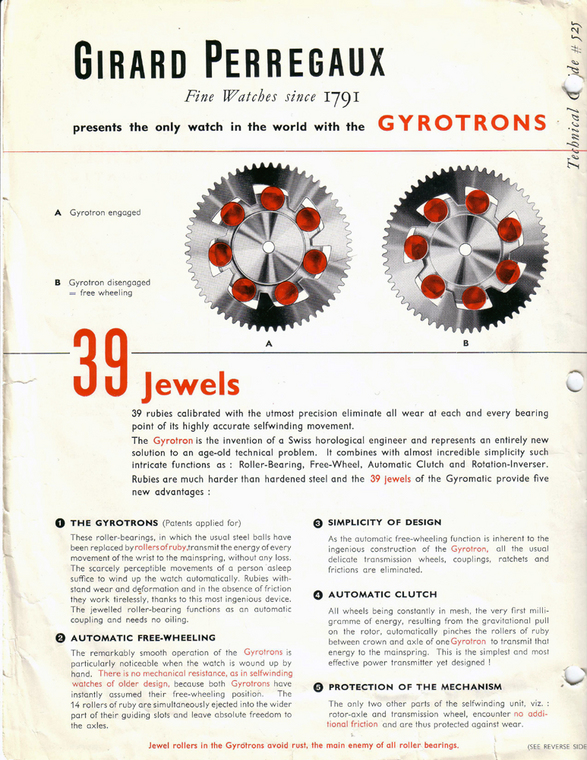

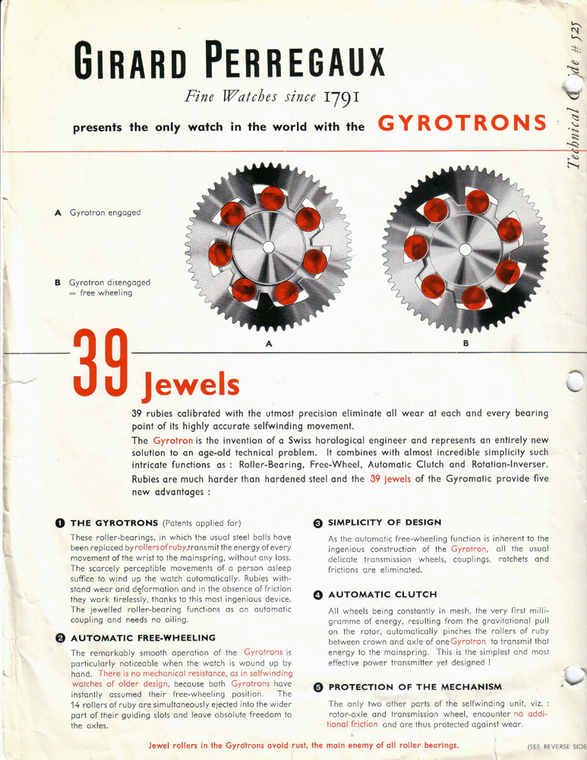

But Dennis what about the one that's got

Gyrotrons

😁😁

Pics from @X350 XJR s FS add that I scored

- Posts

- 25,980

- Likes

- 27,692

JimInOz

··Melbourne AustraliaThanks for the reply. For me personally this is an interesting topic and how people view it.............................

Very interesting Al, I figured there would be a penalty with "changing gears" so it's a bit more than I imagined.

The unidirectional wind does seem to be contradictory but when it's compared with the losses with gear changes/engagements it makes a bit more sense.

Now I'm off to try and figure out what the GP Gyrotron does, besides look cool!

Cheers

Jim

JimInOz

··Melbourne Australia- Posts

- 25,980

- Likes

- 27,692

ulackfocus

·So they are reverser wheels. If each Gyrotron has 7 jewels (I wonder exactly how functional they are), then that caliber actually has 25 jewels in the movement and 14 in the reversers.

JimInOz

··Melbourne AustraliaSo they are reverser wheels. If each Gyrotron has 7 jewels (I wonder exactly how functional they are), then that caliber actually has 25 jewels in the movement and 14 in the reversers.

Extremely so. The jewels are actually cylindrical rollers that jam the inner and outer gubbinses together via the slanting ramp, thus producing a locked assembly. As soon as the direction is reversed, the ramp "unlocks" and the jewels just sit there and allow the outer wheel to spin freely without moving the inner wheel/pinion.

- Posts

- 25,980

- Likes

- 27,692

ulackfocus

·Extremely so. The jewels are actually cylindrical rollers that jam the inner and outer gubbinses together via the slanting ramp, thus producing a locked assembly. As soon as the direction is reversed, the ramp "unlocks" and the jewels just sit there and allow the outer wheel to spin freely without moving the inner wheel/pinion.

Ah, but did they need to be jewels? Could they have been made of metal, or was making those jewels the marketing department's idea so they could advertise 39 instead of 25 jewel movements?

JimInOz

··Melbourne AustraliaAh, but did they need to be jewels? Could they have been made of metal, or was making those jewels the marketing department's idea so they could advertise 39 instead of 25 jewel movements?

I reason that GP used jewels for the same reason they are used bearings for pivots.

Jewels are much harder than steel, therefore they will not wear and don't require lubrication in this application (as steel bearings would have needed to reduce metal to metal fretting).

sdre

·I love posts like this. So educational, and helps me appreciate a certain movement/brand more.

Love it!

Love it!

STANDY

··schizophrenic pizza orderer and watch collectorAh, but did they need to be jewels? Could they have been made of metal, or was making those jewels the marketing department's idea so they could advertise 39 instead of 25 jewel movements?

Are you reading the brochure 🙄

5 new advantages

And the red line at the bottom ( combating the main enemy of all roller bearings )

Archer

··Omega Qualified WatchmakerI reason that GP used jewels for the same reason they are used bearings for pivots.

Jewels are much harder than steel, therefore they will not wear and don't require lubrication in this application (as steel bearings would have needed to reduce metal to metal fretting).

Maybe I'm missing it (smallish text I'm finding hard to read), but I don't see anything in that literature that says these are not lubricated at all. Since in pretty much every wheel train jewel you have a steel pivot riding in a jewel, and those are all lubricated (with some exceptions) I don't think the fact that it's not metal on metal automatically precludes the use of a lubricant.

There are modern reversers without jewels that don't get lubrication on the ratcheting system - Rolex comes to mind specifically, as only the pivots are lubricated, but those are a different design. With modern ETA reversers, it's either a very small amount of 9010 (barely visible on your oiler) or you dip the entire wheel in Lubeta V105, which is a solution that carries a lubricant in it...

And the red line at the bottom ( combating the main enemy of all roller bearings )

Interesting marketing, but in a watch setting far from reality, as rust doesn't just randomly show up inside a watch. If it does, the rolling elements in the reversing wheels are probably the least of your worries...hey my watch is rusted solid, except the reversing wheels so it still winds...yippee! 😀

Also as someone who used to work for a company that made rolling element bearings, the #1 cause of failure was improper installation, usually in the form of failure to lube the bearing properly (too much grease, not enough grease, wrong type of grease, etc.) at least that's what the very extensive legal department our company had was there to prove in case of a failure. 😉

The whole using jewels instead of steel rollers is mostly marketing. Reversing wheels fail in a few ways, but it's rarely the inner working part of the wheel itself that does the locking and unlocking. Modern ETA reversing wheels for example use a ratchet and pawl system, metal on metal contact, and that portion of the wheel rarely fails - here's what those look like:

If anything is going to fail it's usually the pivots wearing, so 99% of the wheels I replace are due to this:

Sometimes it's worn right off - old wheel on the right, new one on the left for comparison:

And in extreme cases, the teeth of the wheel are worn right off - again old one on the right and new on the left for comparison:

But it's fun to look at the old brochures to see how these things were marketed.

Cheers, Al

Similar threads

- Posts

- 5

- Views

- 4K

- Posts

- 7

- Views

- 7K