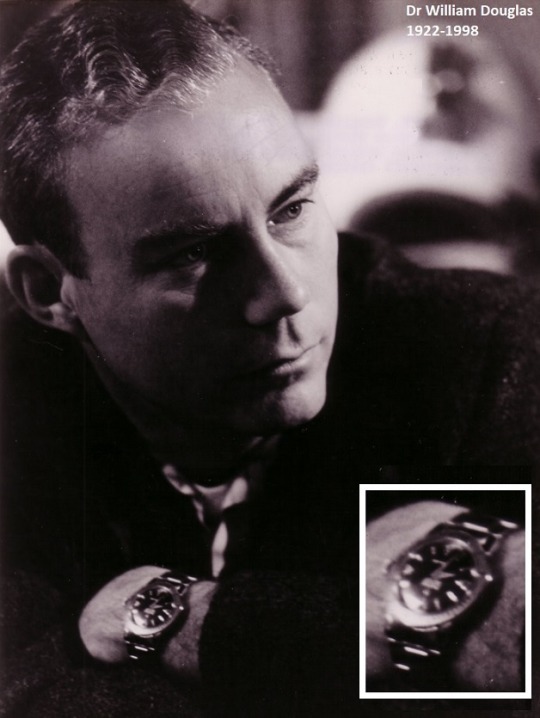

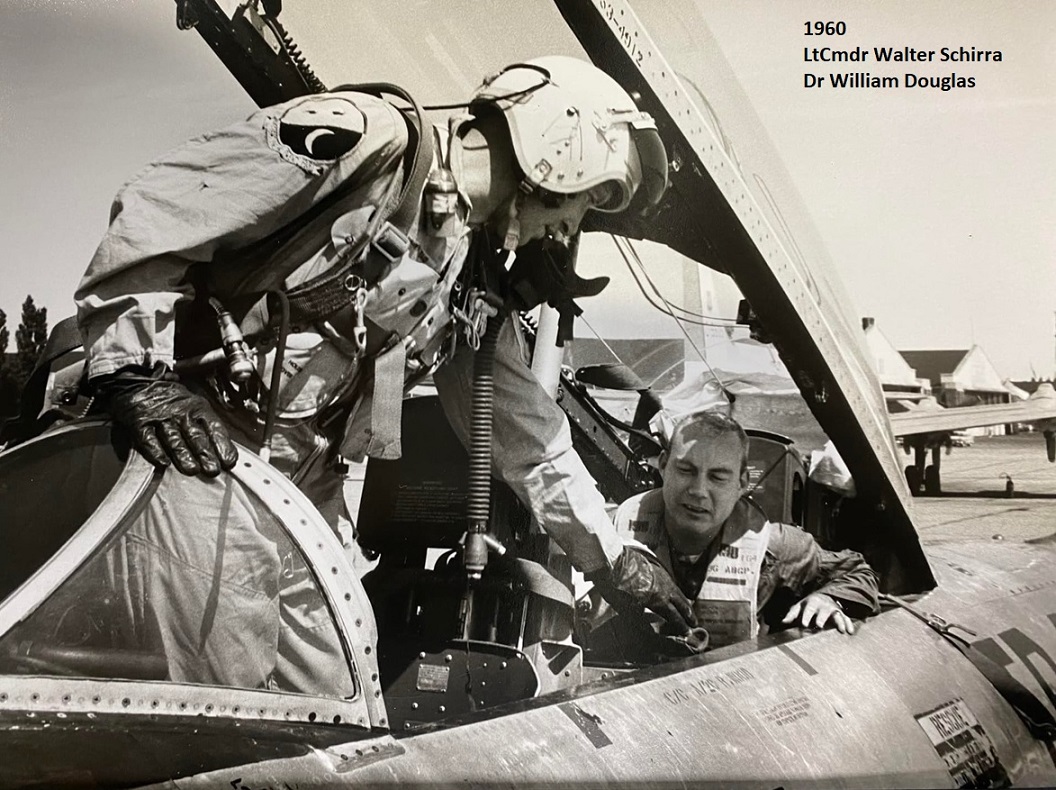

It’s nice to be able to share with other space enthusiasts. While many of these documents offer tantalizing snapshots of the early Mercury program, what is particularly engaging is the overall sense of the character of Dr. William Douglas that the documents reveal, a man who played a significant role in the early space program, and a man who I had not previously appreciated or known much about.

This post shares some evidence about why Dr. Douglas was an important contributor to the space program.

BACKGROUND INTRODUCTION TO DR. DOUGLAS

Seated in alphabetical order at a long table, on April 9, 1959, NASA formally introduced its seven Mercury astronauts to the world. After a brief photo session, for the next 90 minutes the new astronauts answered question after question from the reporters. Space was a completely new, exciting field and the reporters weren’t satisfied with the technical facts about space travel, they wanted to know how it

felt to be an astronaut. A question and answer by John Glenn remains one of the most memorable from that day. After a reporter asked which medical test the astronauts liked the least, Glenn responded: “It’s rather difficult to pick one. If you figure how many openings there are on the human body and how far you can go into any one of them… you answer, which would be the toughest for you?”

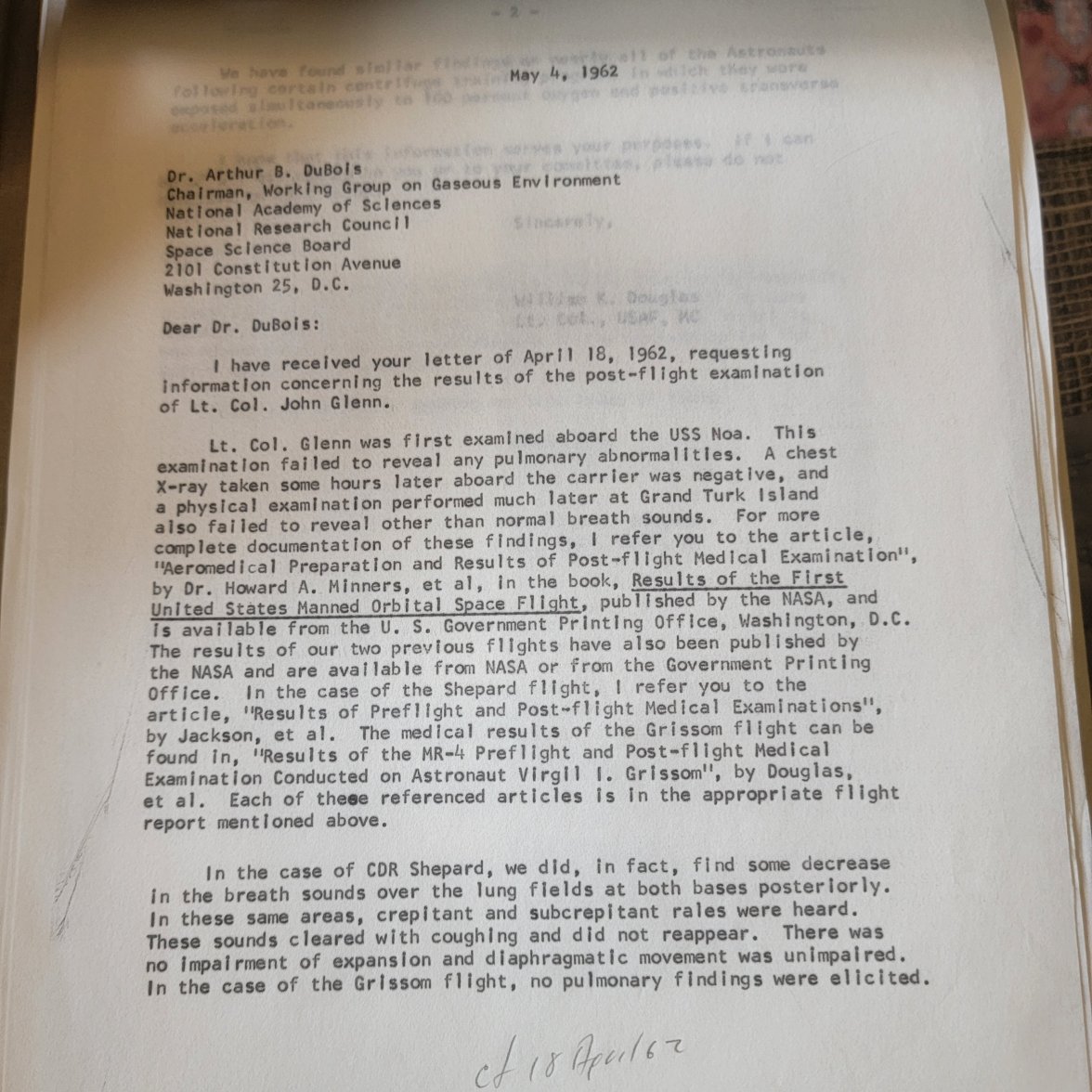

Prior to selection, each astronaut candidate completed approximately a week of medical evaluations, (which Dr. Douglas did not conduct.) NASA’s Project Mercury reports that “over 30 different laboratory tests collected chemical, encephalographic, and cardiographic data. X-ray examinations thoroughly mapped each man’s body. The ophthalmology section and the otolaryngology sections likewise learned almost everything about each candidate’s eyes, and his ears, nose, and throat. Special physiological examinations included bicycle ergometer tests, a total-body radiation count, total-body water determination, and the specific gravity of the whole body. Heart specialists made complete cardiological examinations, and other clinicians worked out more complete medical histories on these men than probably had ever before been attempted on human beings.”

With John Glenn’s answer, he set the tone that doctors were a necessary but unpleasant partner. NASA may have intended to only introduce the Mercury 7 astronauts to the nation and the world, but they also firmly established that medical doctors and specialists were intimately involved with the program.

Each Mercury 7 astronaut was a pilot, which meant they were already fully aware of the authority of doctors through the role of the flight surgeon. The astronauts favorite nurse, Dee O’Hara once explained to a BBC interviewer that “Medics were not their favorite people, especially flight surgeons, as they knew flight surgeons had the power to ground them and that’s the last thing they wanted.”

The public took their cue from their astronaut heroes. During launches, the public was aware of the importance of medical staff, as flight surgeons were part of the list of people who responded to the Flight Director’s call for Go or No-Go to proceed with the launch. At times the medical staff seemed like comic relief, excessively nervous hypochondriacs who resented the risks taken by their patients during a mission. When Michael Collins’s electrical attachments came undone during the translunar injection for Apollo XI, the flight surgeon commented that he had lost Collins’ data, to which Collins replied, “don’t worry Control, if I stop breathing, I will tell you.”

Some of this negativity was earned. James Donovan in his book,

Shoot For The Moon, describes a flight-readiness meeting that took place on June 12, 1969, a little more than a month before the scheduled launch date for Apollo XI. The Director of the Apollo program, General Sam Phillips met with his dozen senior Apollo managers to ask if the July 16 launch date was a go or if they needed to wait another month. “The last man to give his opinion was Dr. Charles Berry, the surgeon in charge of the astronauts and a man disliked by most of them. He appeared frequently on televised press conferences, where he billed himself as their personal doctor, but they rarely saw him. He told Phillips that he had a ‘gut feeling’ that the crew would not be in the best condition for a July launch, though his reasons were vague.” After re-asking each manager to simply say “Go” or “No-Go,” Phillips decided that the mission would launch as scheduled on July 16.

But this relationship that the astronauts had with the flight surgeon wasn’t always like this.

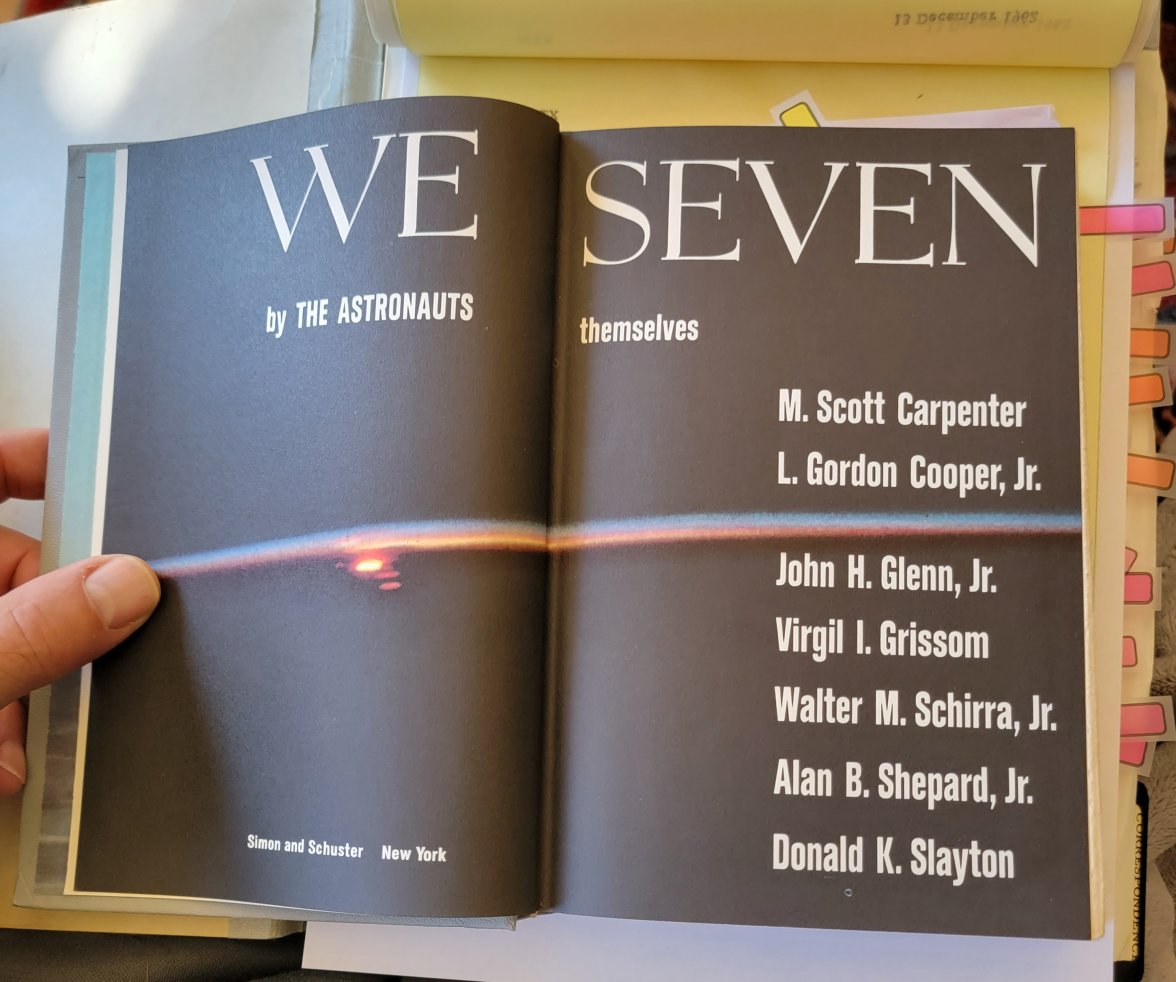

In one of the first books about the Mercury 7 Astronauts,

We Seven, published in 1962, John Glenn describes in detail what it was like to ride the centrifuge. In a chapter entitled, “The Wheel”, Glenn writes:

“We got used to the sensations as time went on, however. I do not believe that a person actually builds up a physical tolerance to G forces, but you do develop various techniques for coping with them and you get more or less inured to the stresses they put on you….We were all in good physical shape before we started taking the rides, however. We were exercising regularly and keeping ourselves in shape for the training. Also, Bill Douglas, our flight surgeon, checked us over carefully before and after each trip…Bill usually monitored the controls while the centrifuge was operating, and he had graphs in front of him which showed our respiration and heart rate. A closed-circuit TV camera mounted inside the gondola let him watch our faces for signs of strain or unconsciousness. If Bill had any indication of trouble he could flip a switch to bring the gondola to a fast stop.”

The following excerpt may be the most insightful about the character of Dr. Douglas and of the trust and admiration that the Mercury 7 astronauts had for him.

“In addition to all this, Bill took runs on the centrifuge ahead of us so he would know in advance what we were going through. I call that a real fine bedside manner…Bill Douglas made a number of runs on the centrifuge to simulate what it would be like if the capsule started to tumble in space and expose us to a quick succession of high positive and negative Gs. Your head snaps forward on a run like this, and your legs tend to fly out of the couch. Both [the other doctor] Augerson and Douglass made these runs at various rates of rotation and at various angles to see what the effect would be when the capsule was tumbling at various speeds and was in various specific attitudes when the tumbling began. They tried everything out in both pressurized and unpressurized sits and with the pressure inside gondola varying all the way from sea level to the five pounds per square inch we would normally have inside the capsule. Out of all this, we got some good advice. We had experienced some pain on the higher G runs-up around 16-and Bill Douglas suggested that we grunt and squeeze out words to relieve the pain. He told us this procedure would help pump blood from the abdomen, where it was pooling, and back in the heart by changing the pressure in the thorax. The change in pressure that you get as a result of grunting acts as a pump itself, and this relieves the heart of some extra work. The technique worked fine and it made some of our runs on the wheel a good deal easier.”

The book

We Seven does not list an author. Instead, it reads “by The Astronauts themselves.” In addition to stories by the astronauts, there is a lengthy introduction by John Dille, a senior editor for LIFE magazine. The introduction is italicized, establishing that when text appears in italics throughout the book, that section is written by John Dille.

An italicized section written by John Dille follows John Glenn’s excerpt from above:

“

Lieutenant Colonel William Douglas, a handsome, soft-spoken Air Force flight surgeon with prematurely graying hair and a penchant for studying the stars with his worn telescope, had what was undoubtedly the most unique practice in U.S. medicine. He not only guided his seven prized patients through the physical perils of training and actual flight, but he also served as friend, confidant and personal physician to the Astronauts and their families. He did, indeed, have the perfect bedside manner.

“’I went through the tests with the boys,’ he explained, ‘so I could speak their language-and so they could never tell me I didn’t know what I was talking about. I took the full Redstone profile-up to 11 Gs. And I made the other runs that we know might made them dizzy. I figured that if I could tell them whenever they got into trouble that this

has helped me

, they might take my advice and benefit from it. They didn’t always take it. Some of them grunted to help them breathe and some did not. They all figured out their own capacity, and it was not always the same. Here again, they were all different. There were no two of them alike.’”

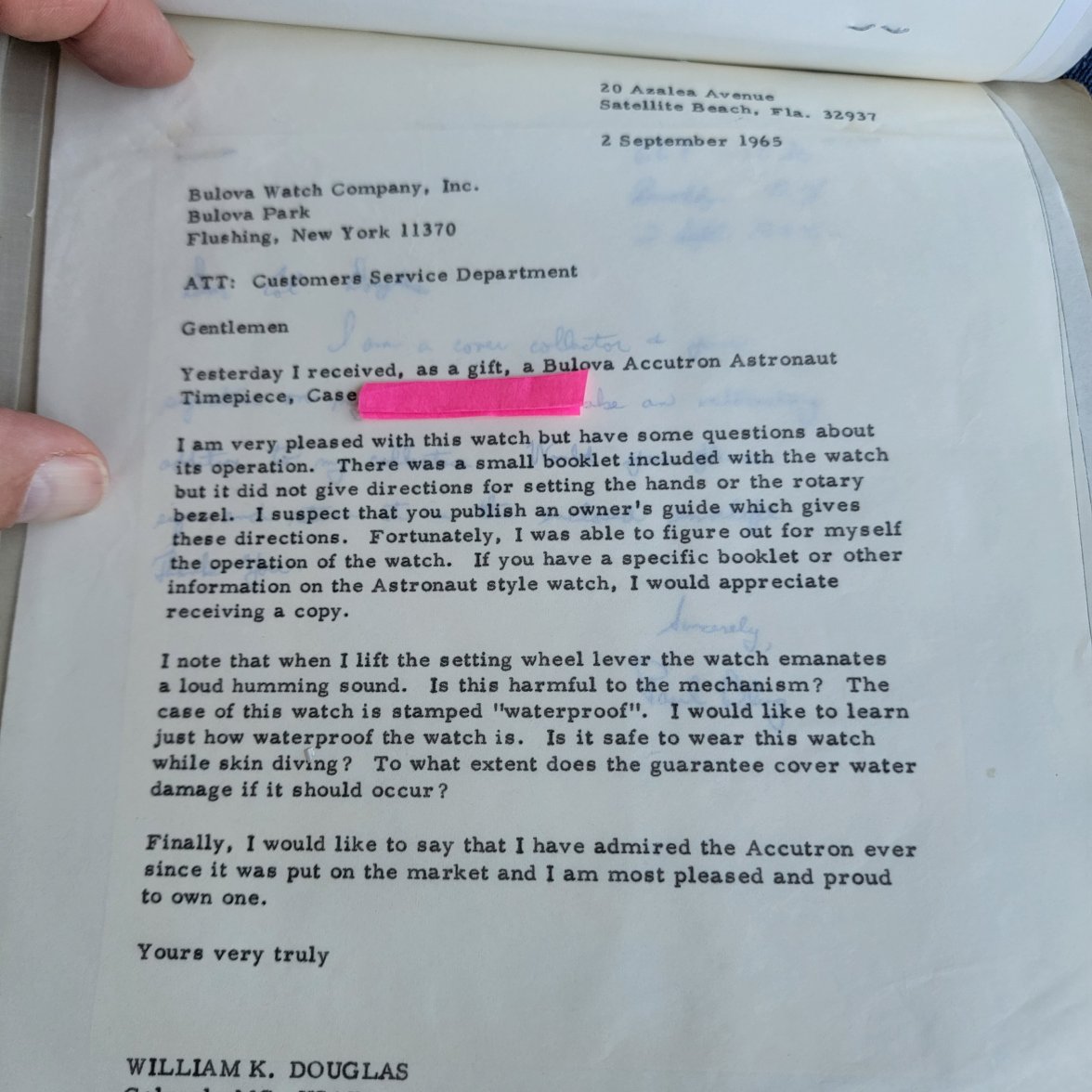

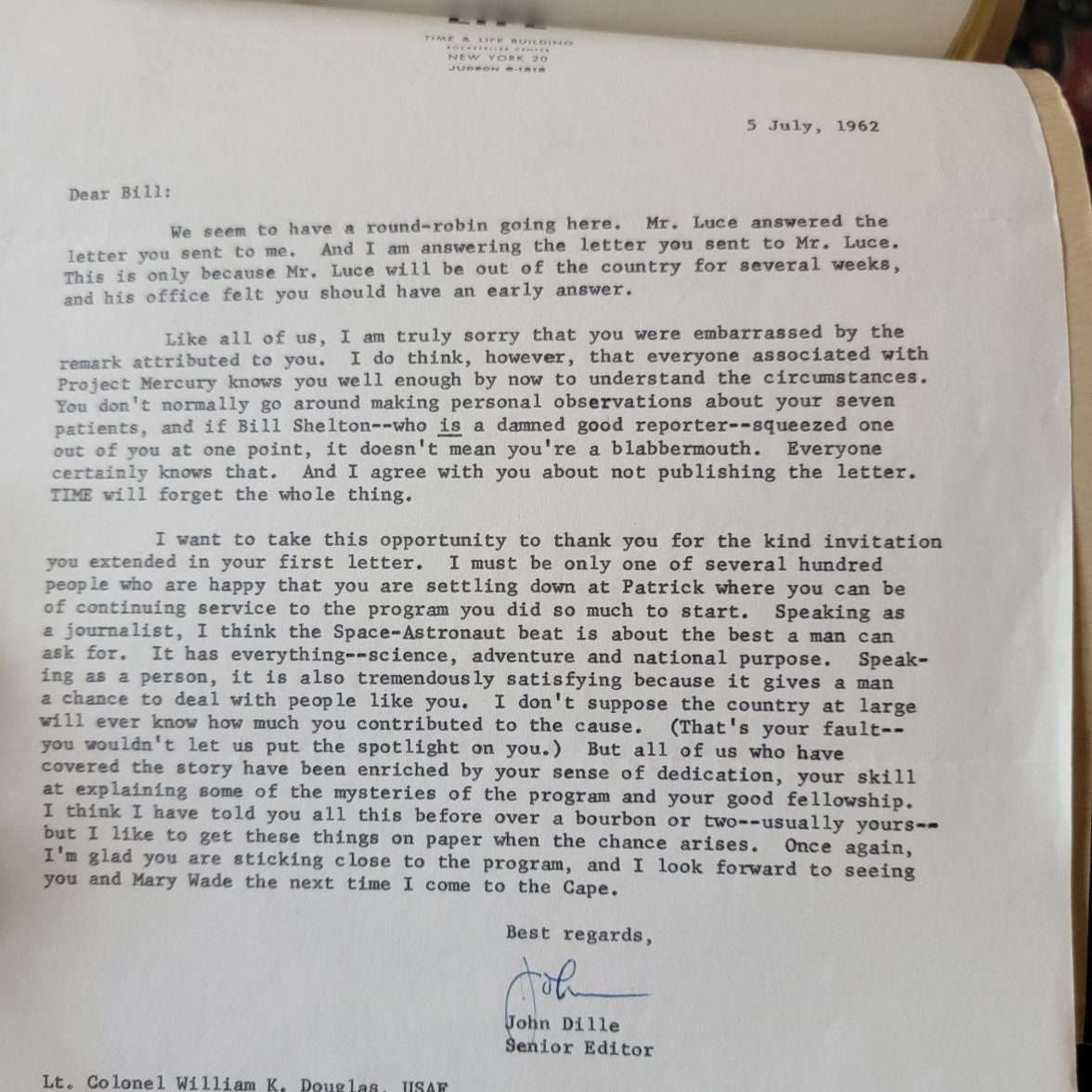

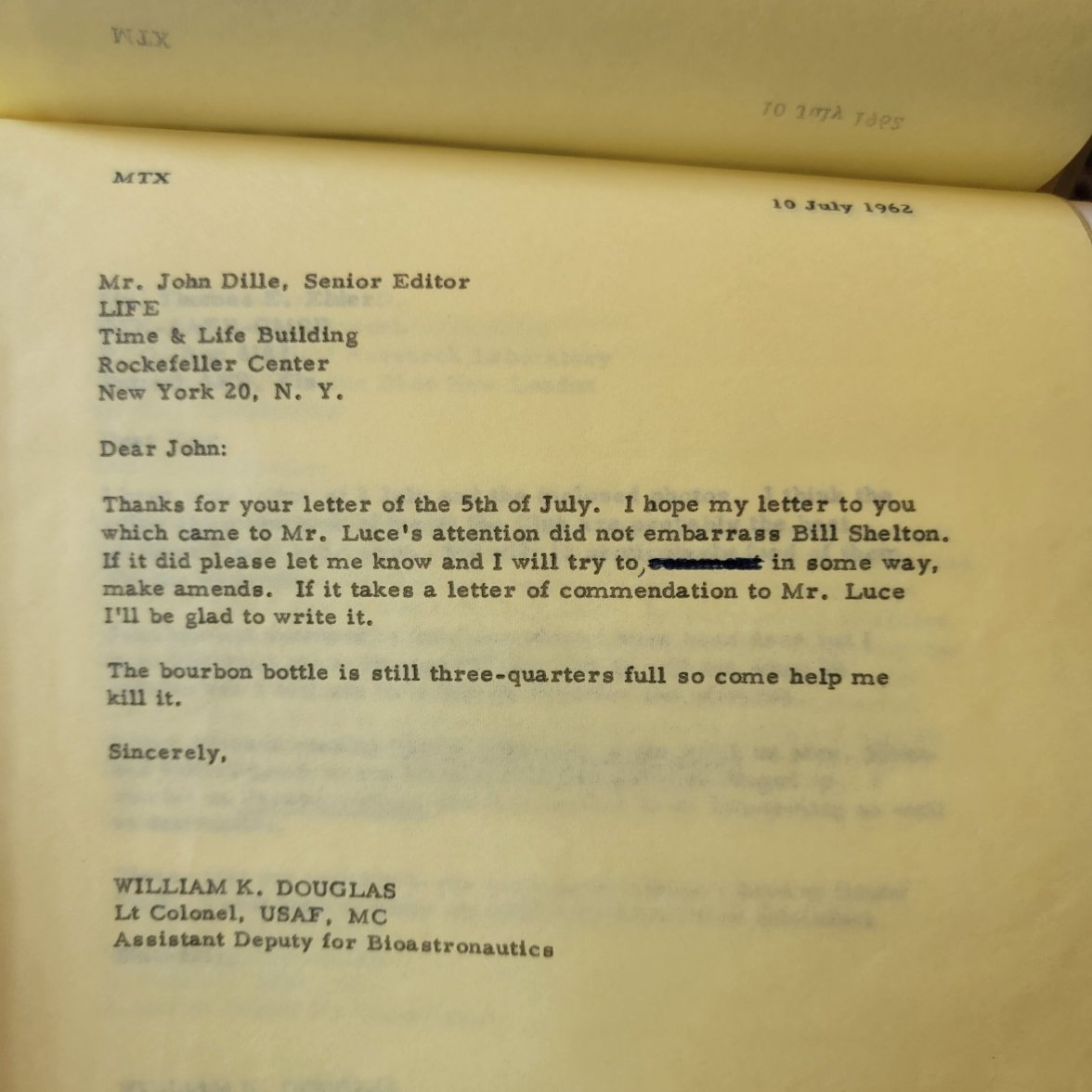

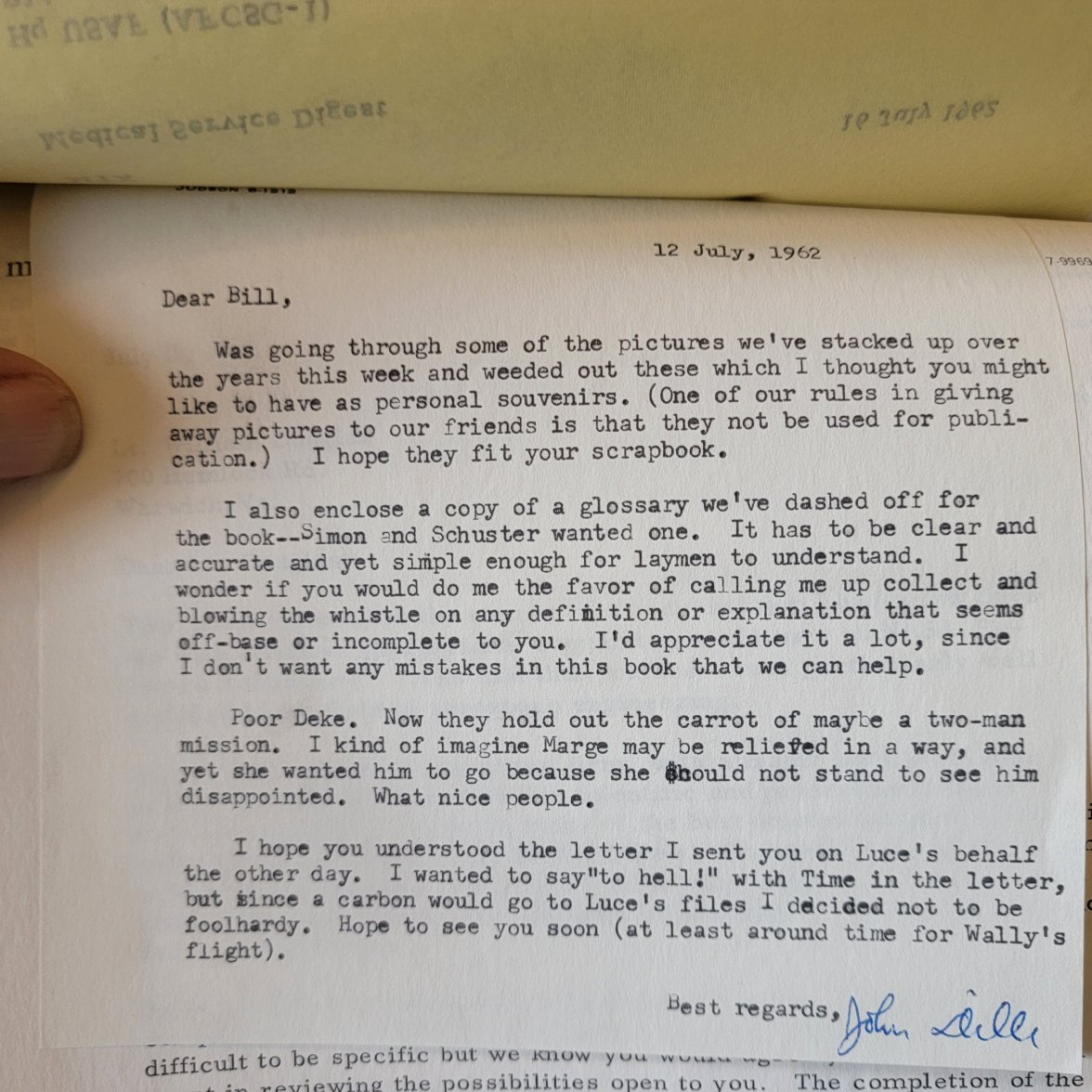

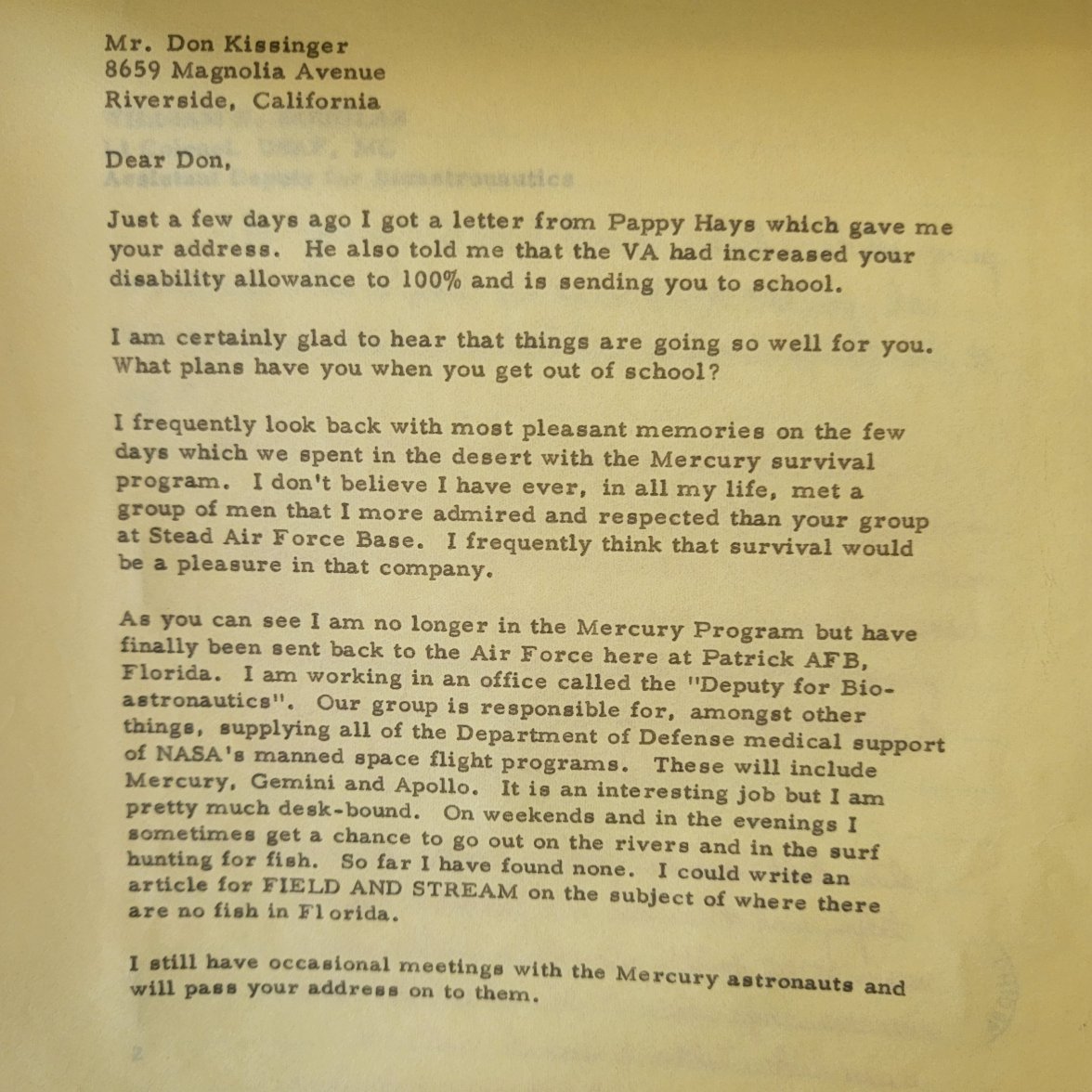

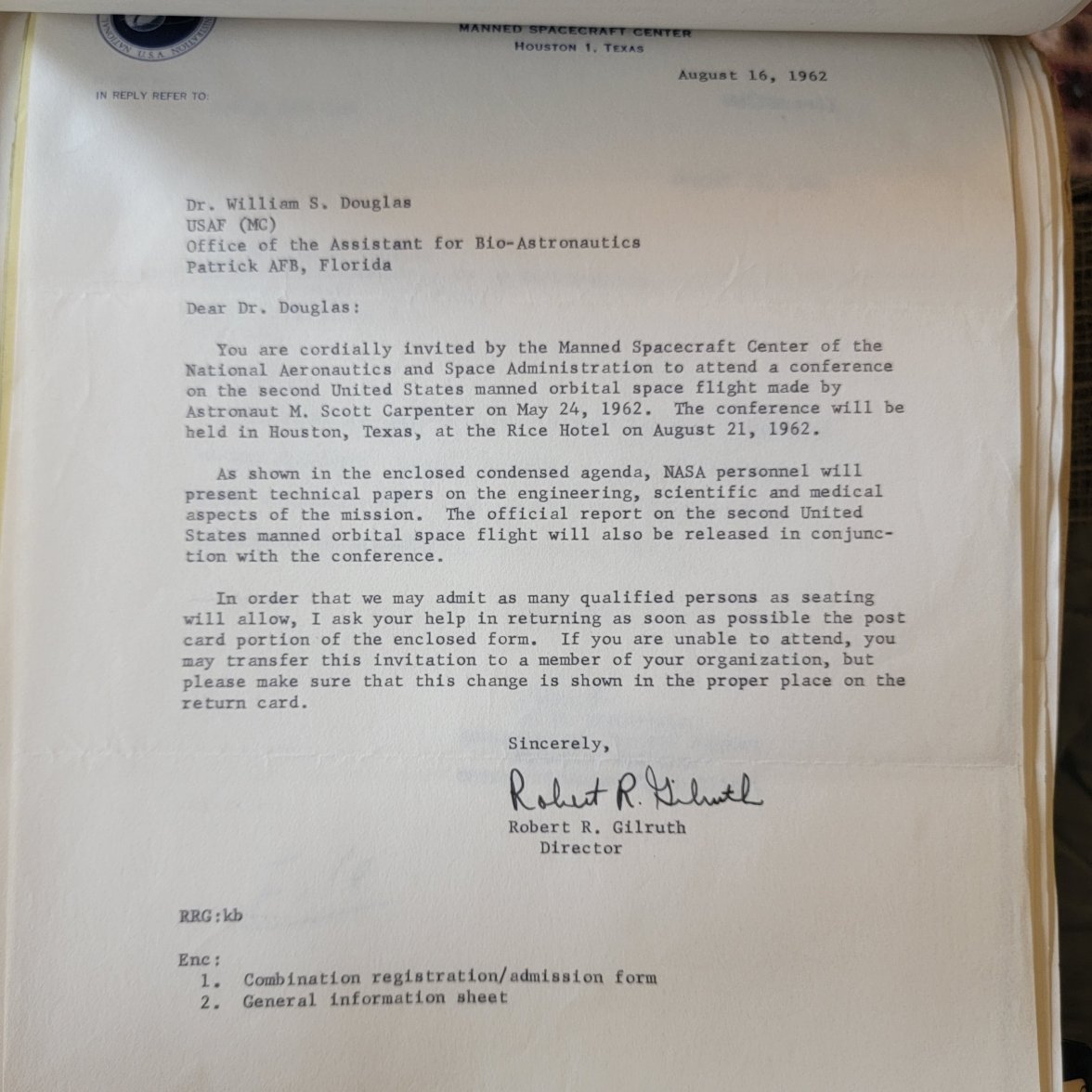

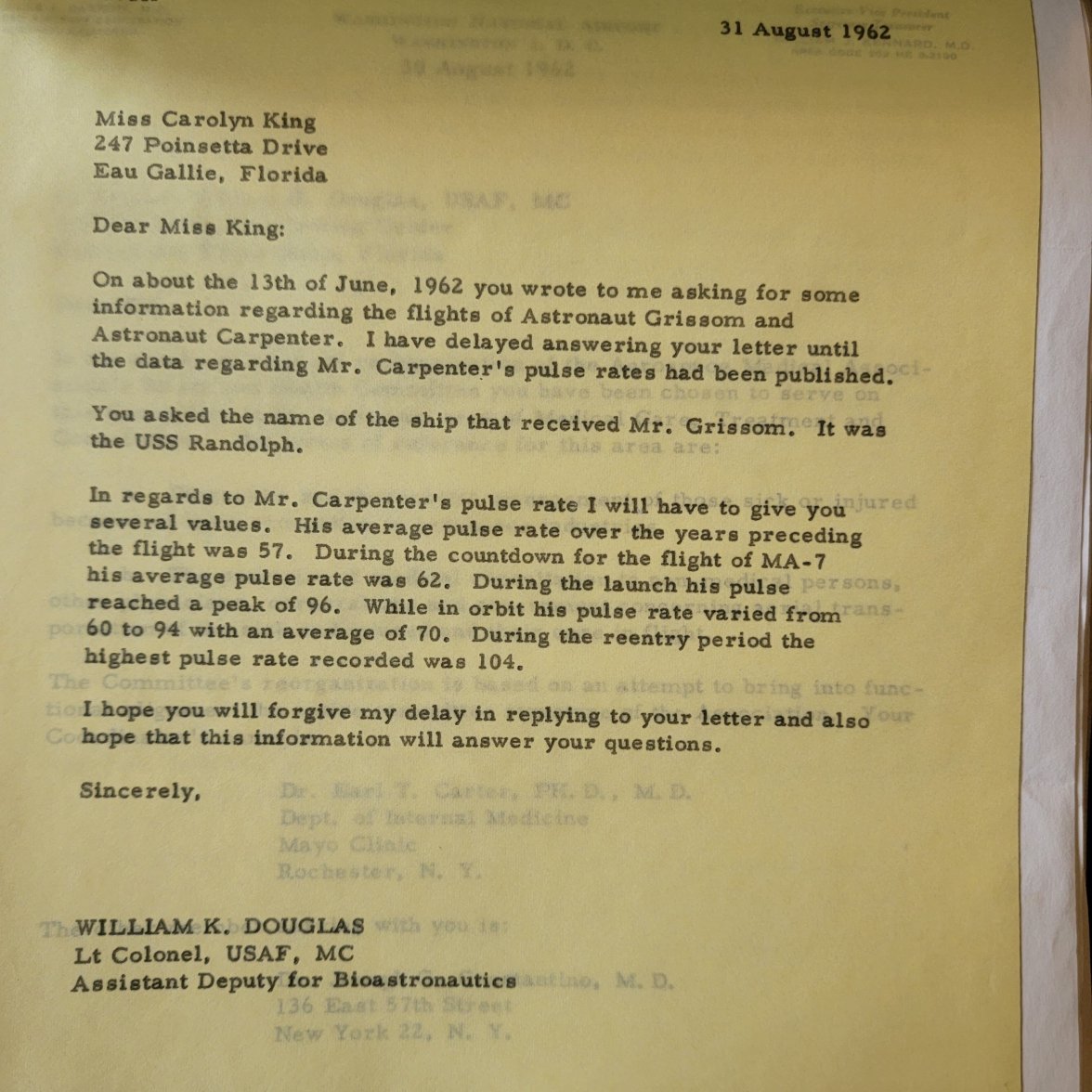

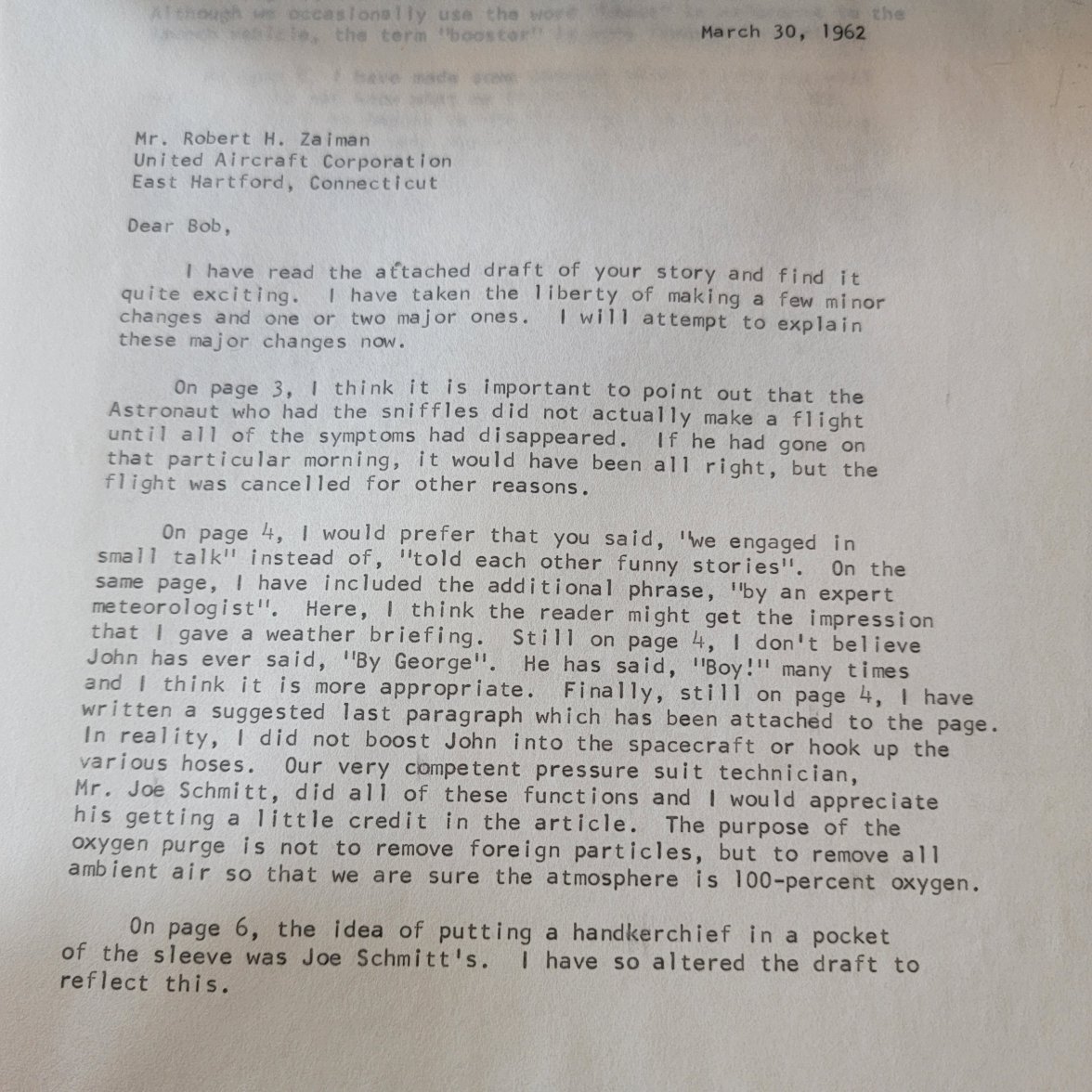

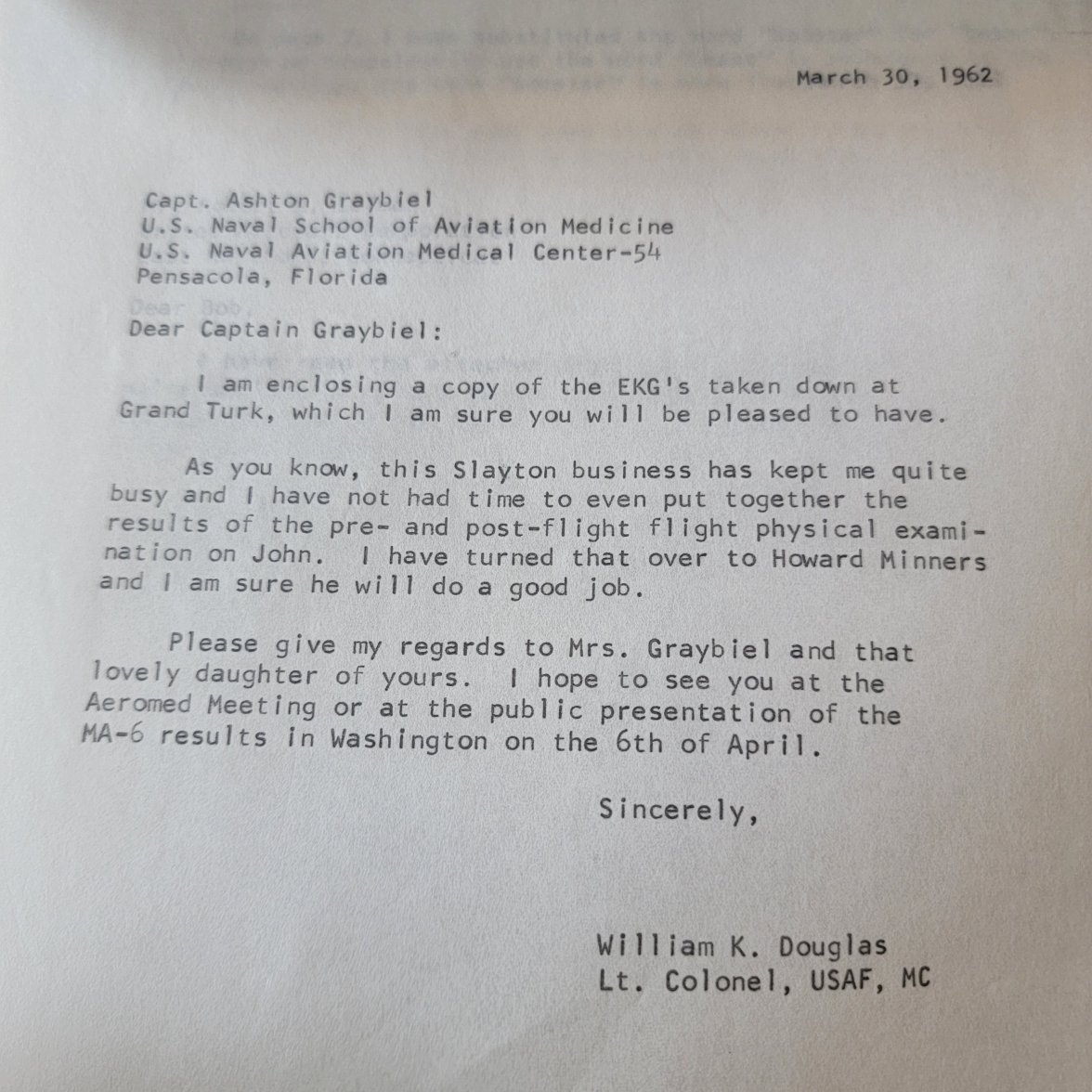

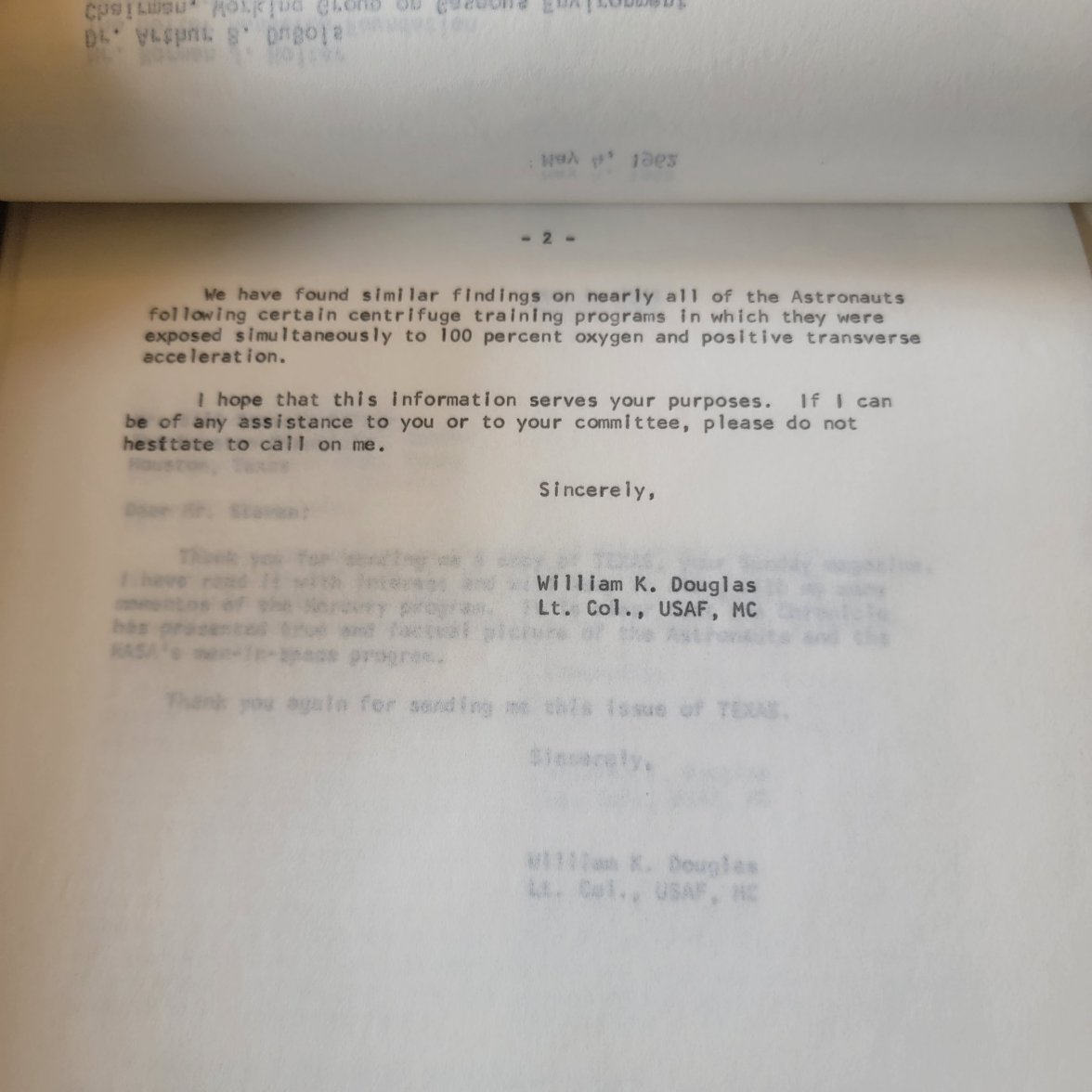

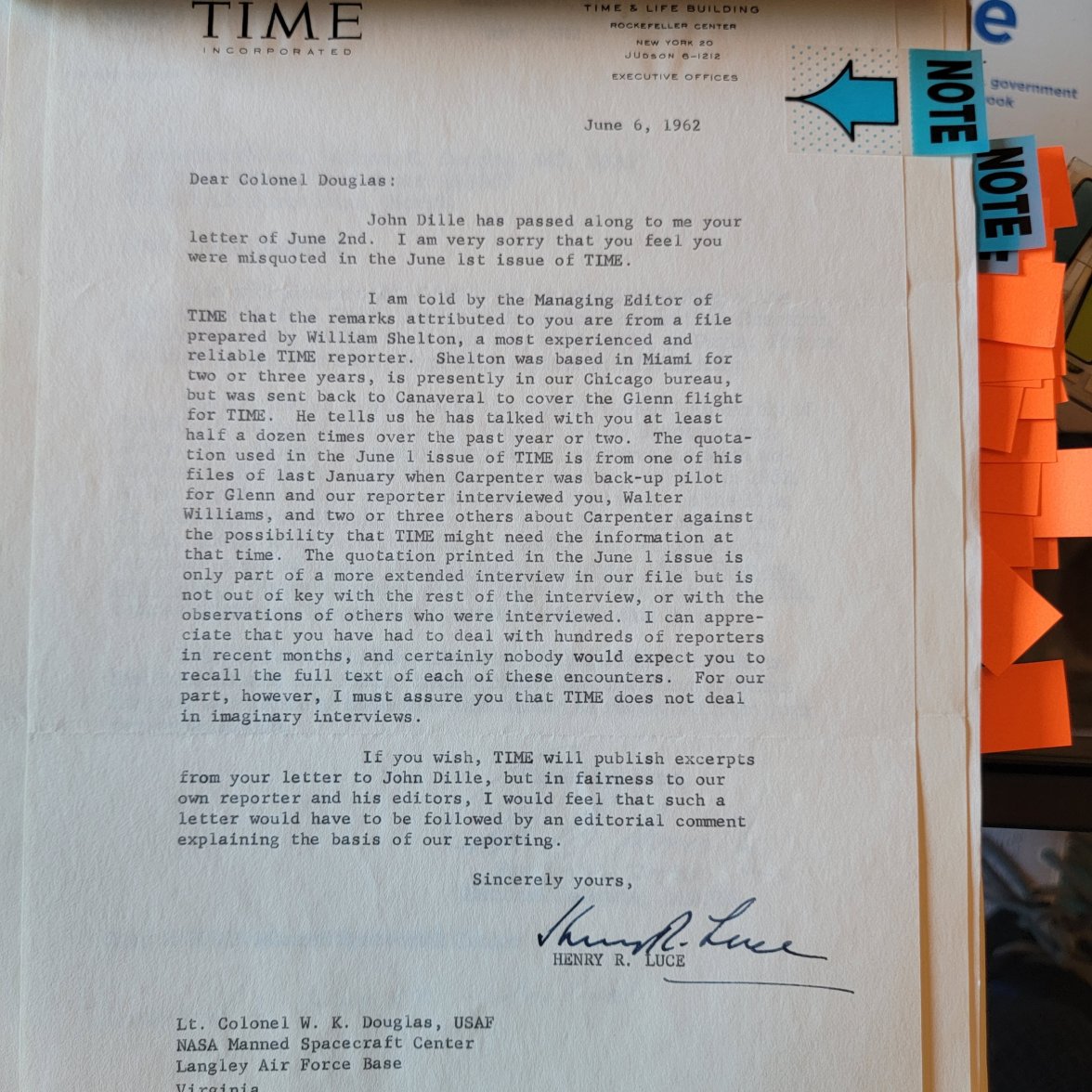

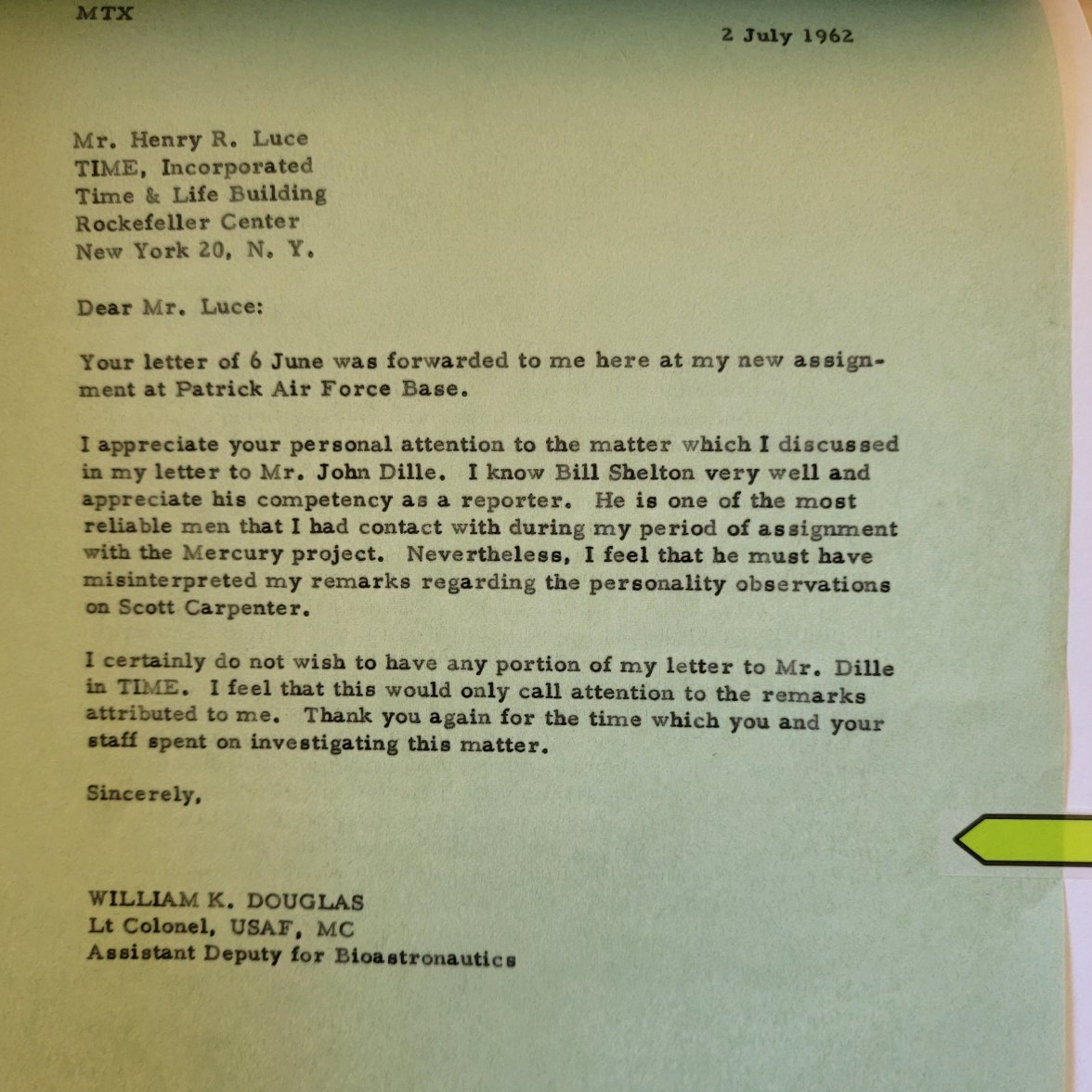

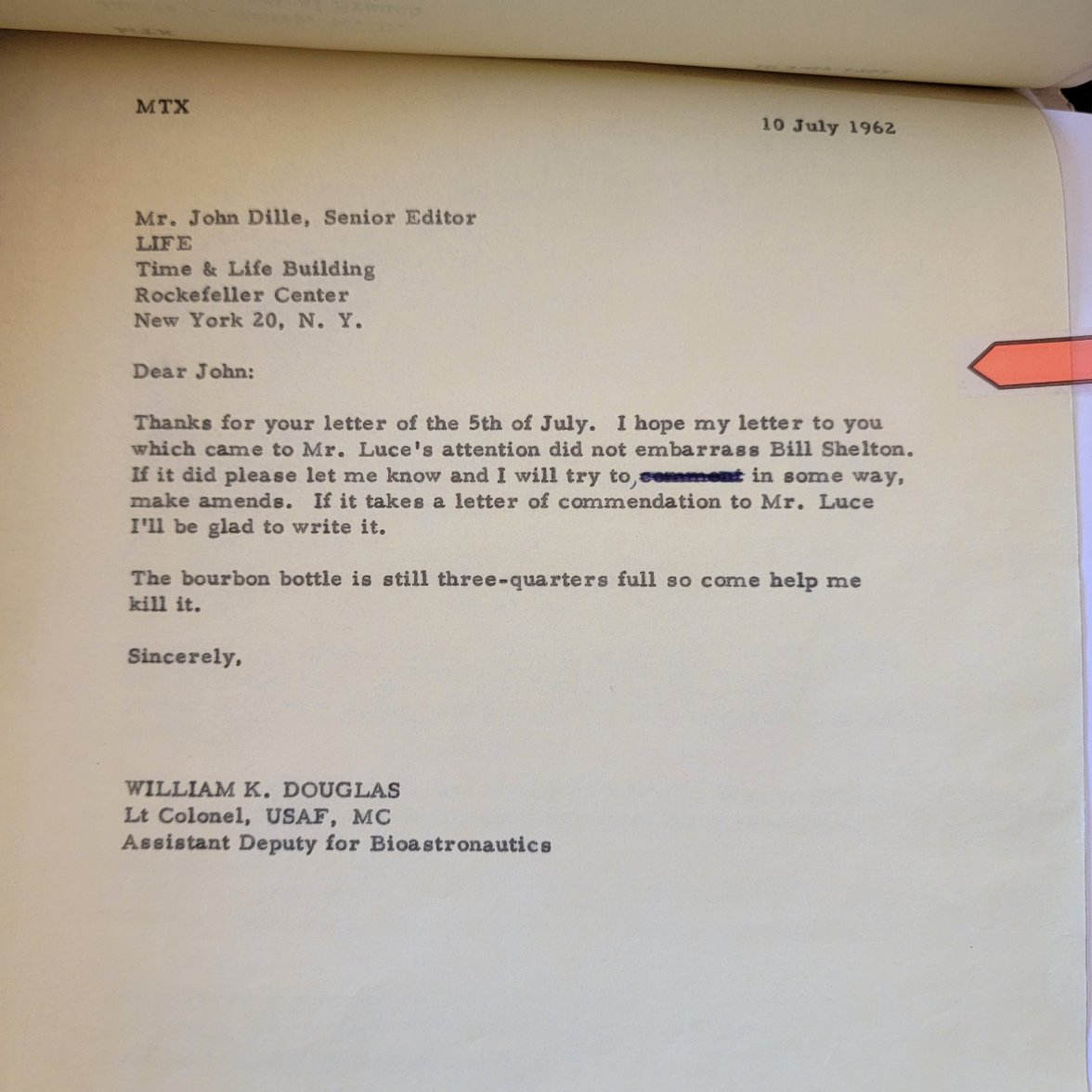

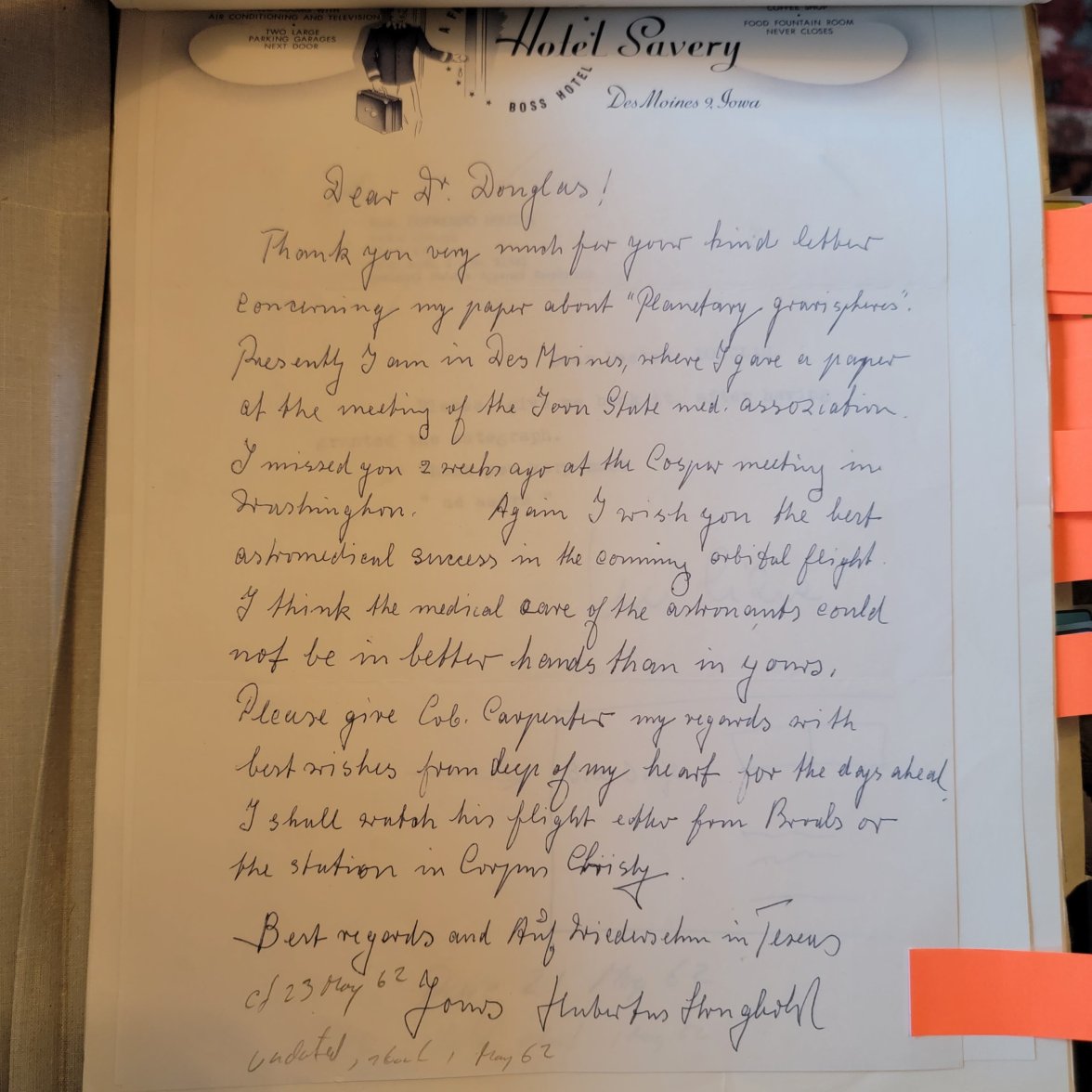

Dr. Douglas kept a copy of correspondence he had with John Dille and Henry Luce, who founded Time, Life, Fortune, and Sports Illustrated, as well as correspondence with other publishers, such as National Geographic. The letters between Luce and Dille relate to an incident where Dr. Douglas felt he was misquoted. It suggests that Dr. Douglas was protective of his relationship with the astronauts and did not want to do anything to jeopardize that relationship.

In a follow-up letter from John Dille to Dr. Douglas, Dille writes the following:

“Speaking as a journalist, I think the Space-Astronaut beat is about the best a man can ask for. It has everything—science, adventure and national purpose. Speaking as a person, it is also tremendously satisfying because it gives a man a chance to deal with people like you. I don’t suppose the country at large will ever know how much you contributed to the cause. (That’s your fault—you wouldn’t let us put the spotlight on you.) But all of us who have covered the story have been enriched by your sense of dedication, your skill at explaining some of the mysteries of the program and your good fellowship.”

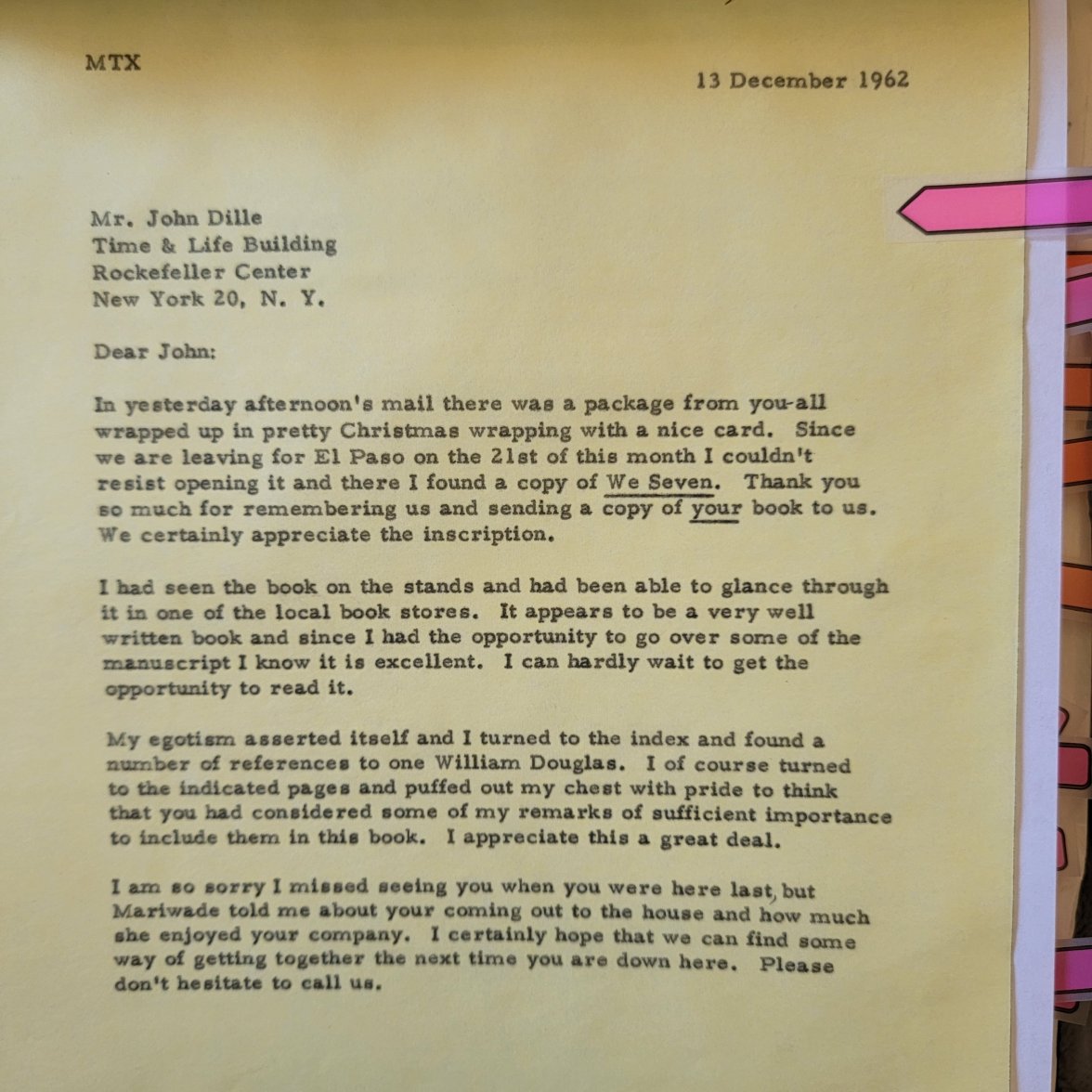

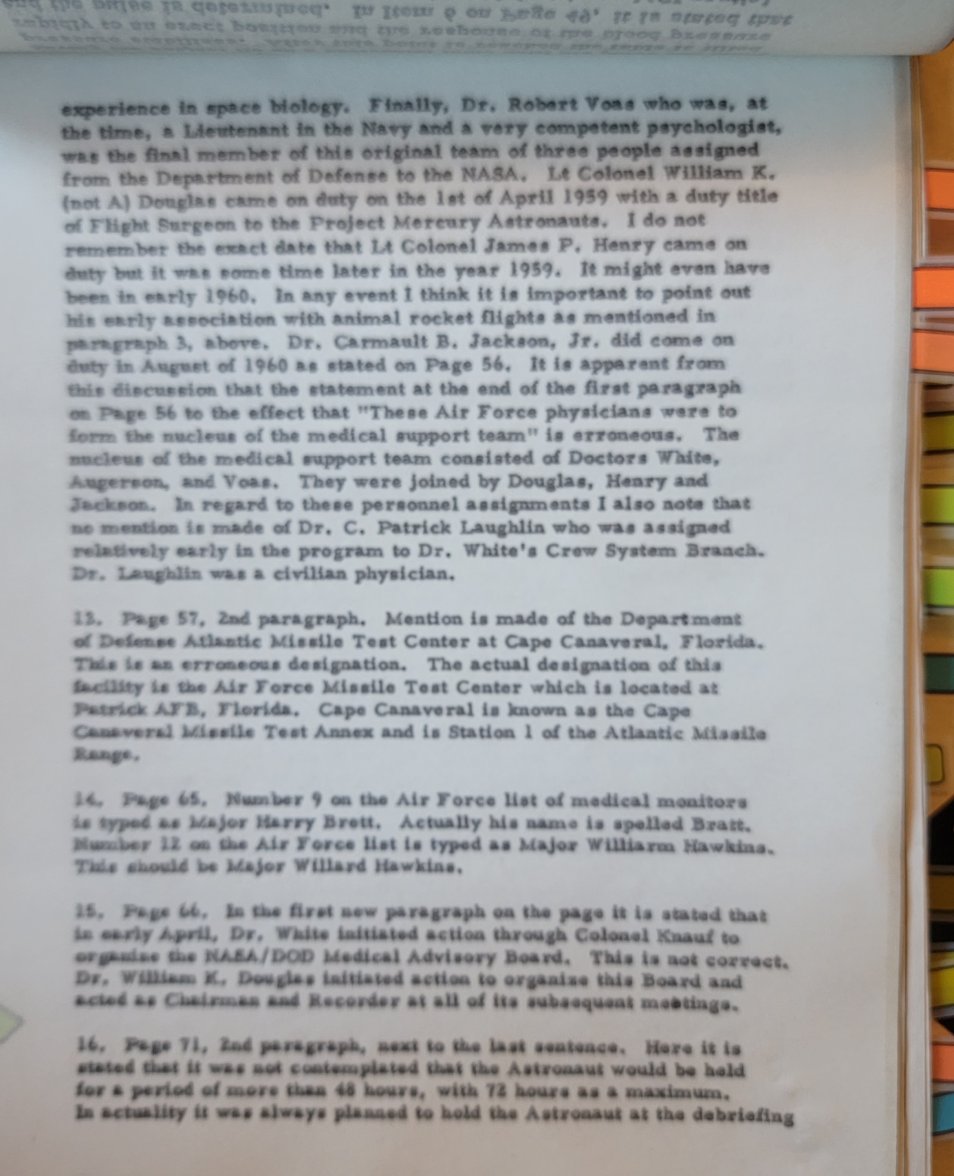

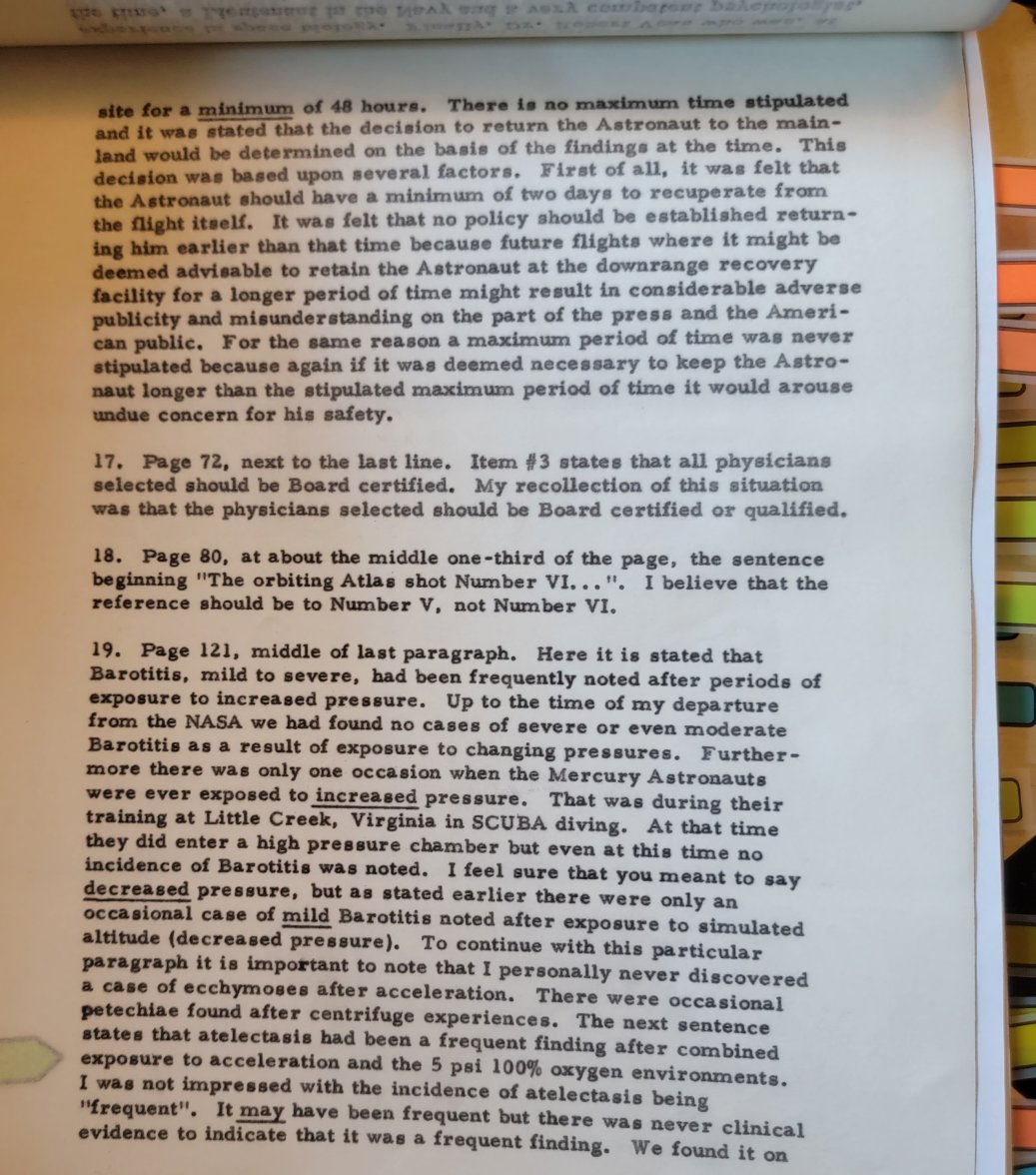

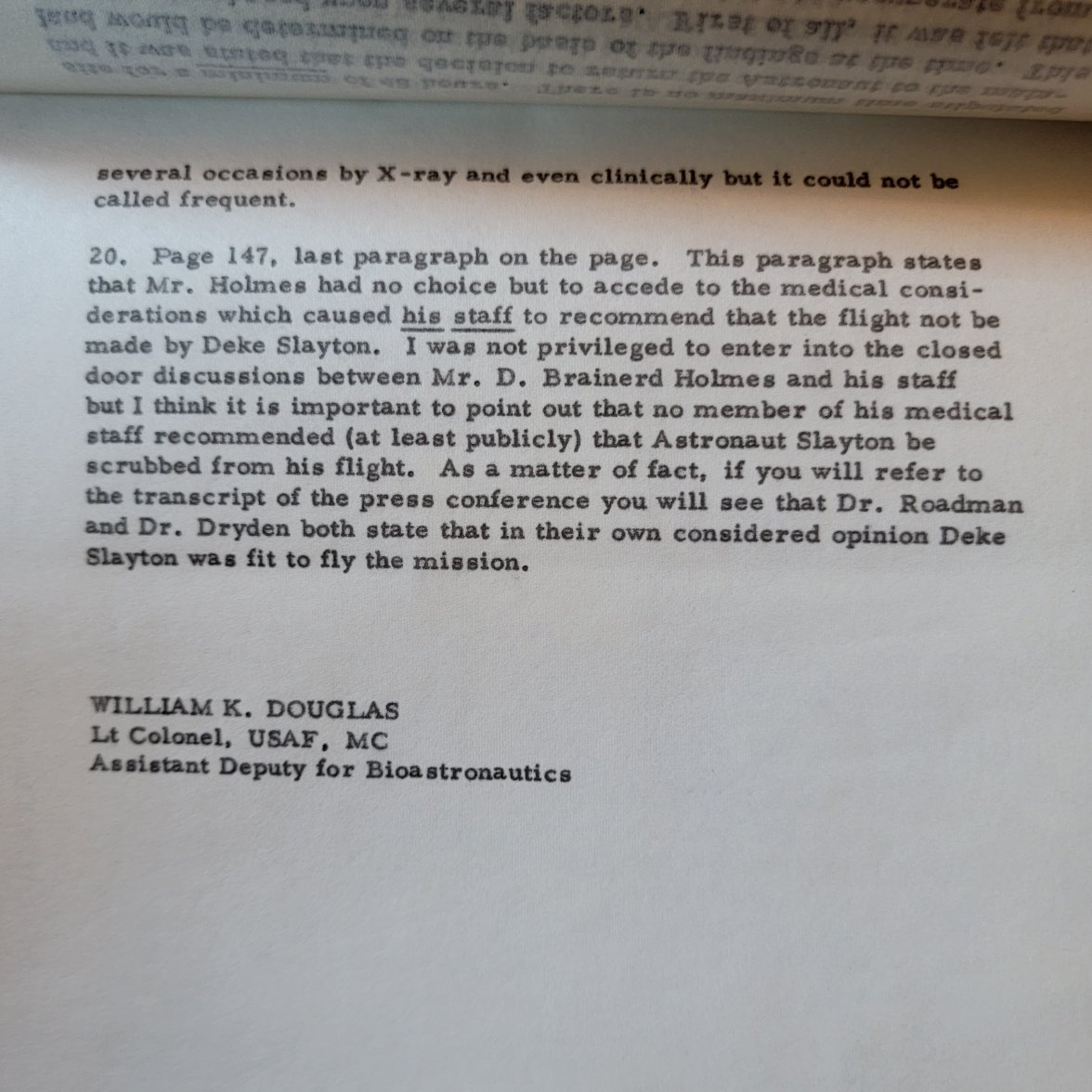

Dr. Douglas also commented on reading the book,

We Seven;

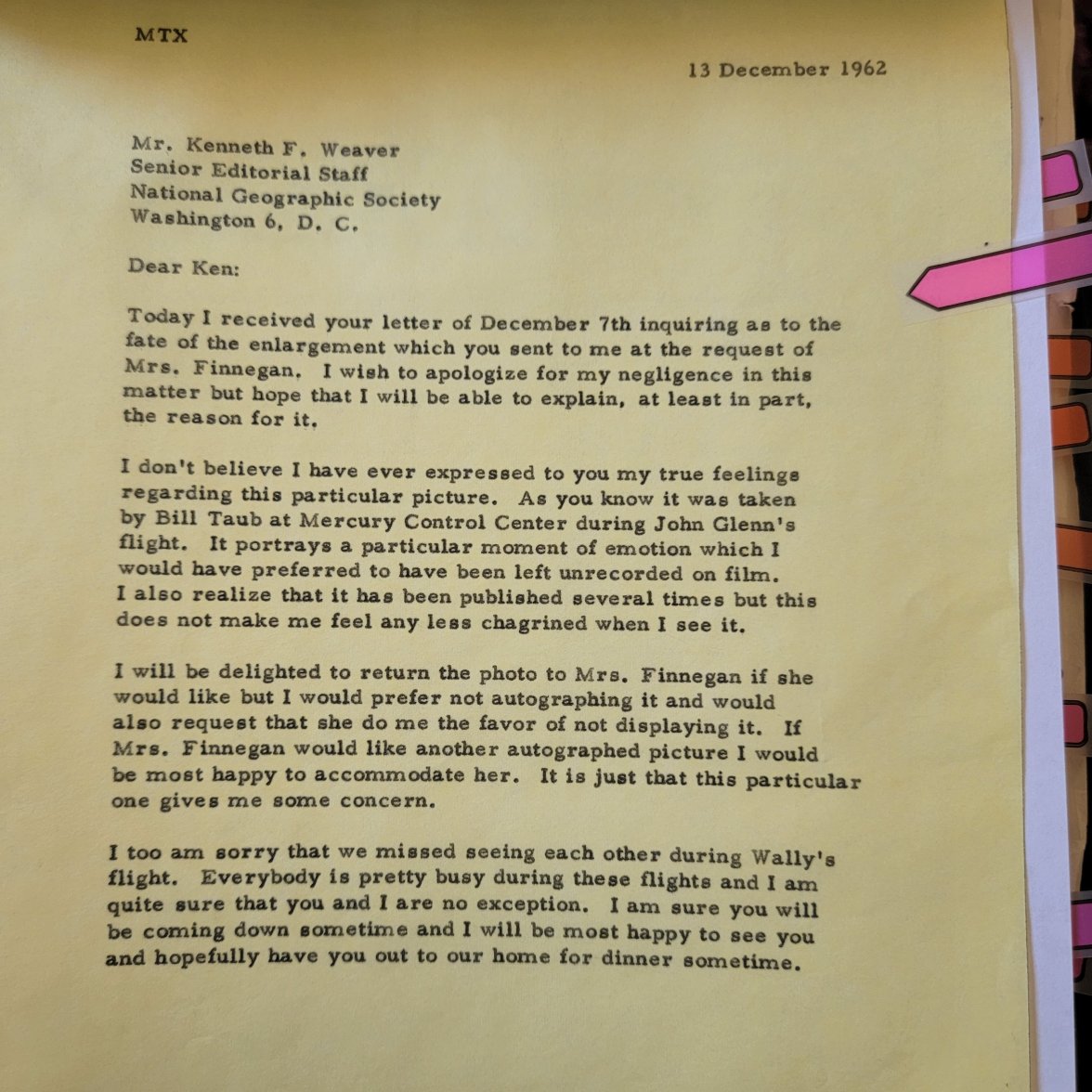

in a different topic, Dr. Douglas responds to a request from National Geographic regarding an autograph on a photo. Dr. Douglas says he does not feel comfortable as the photo does not reflect well on the astronaut. (I couldn't find out which photo it referenced.)

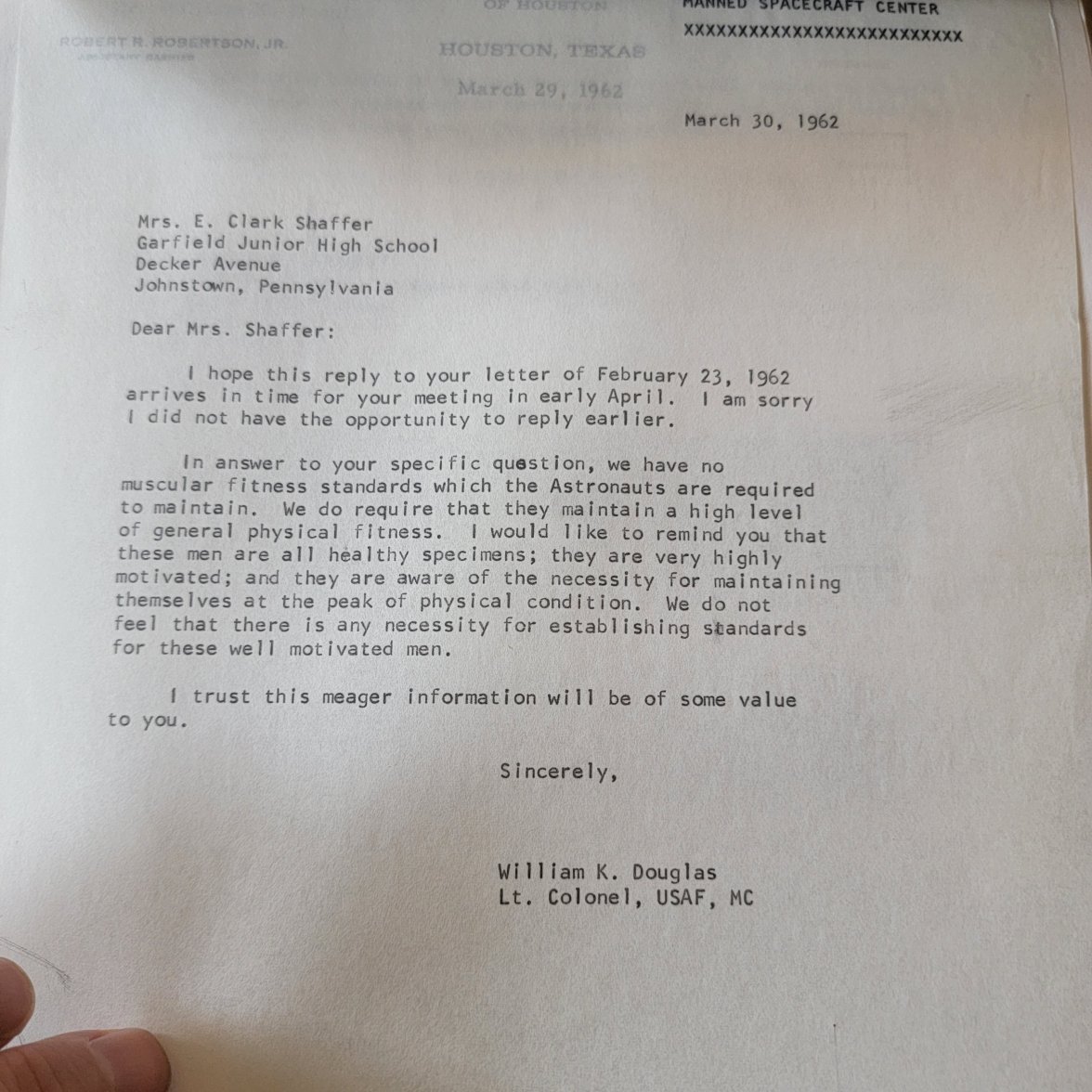

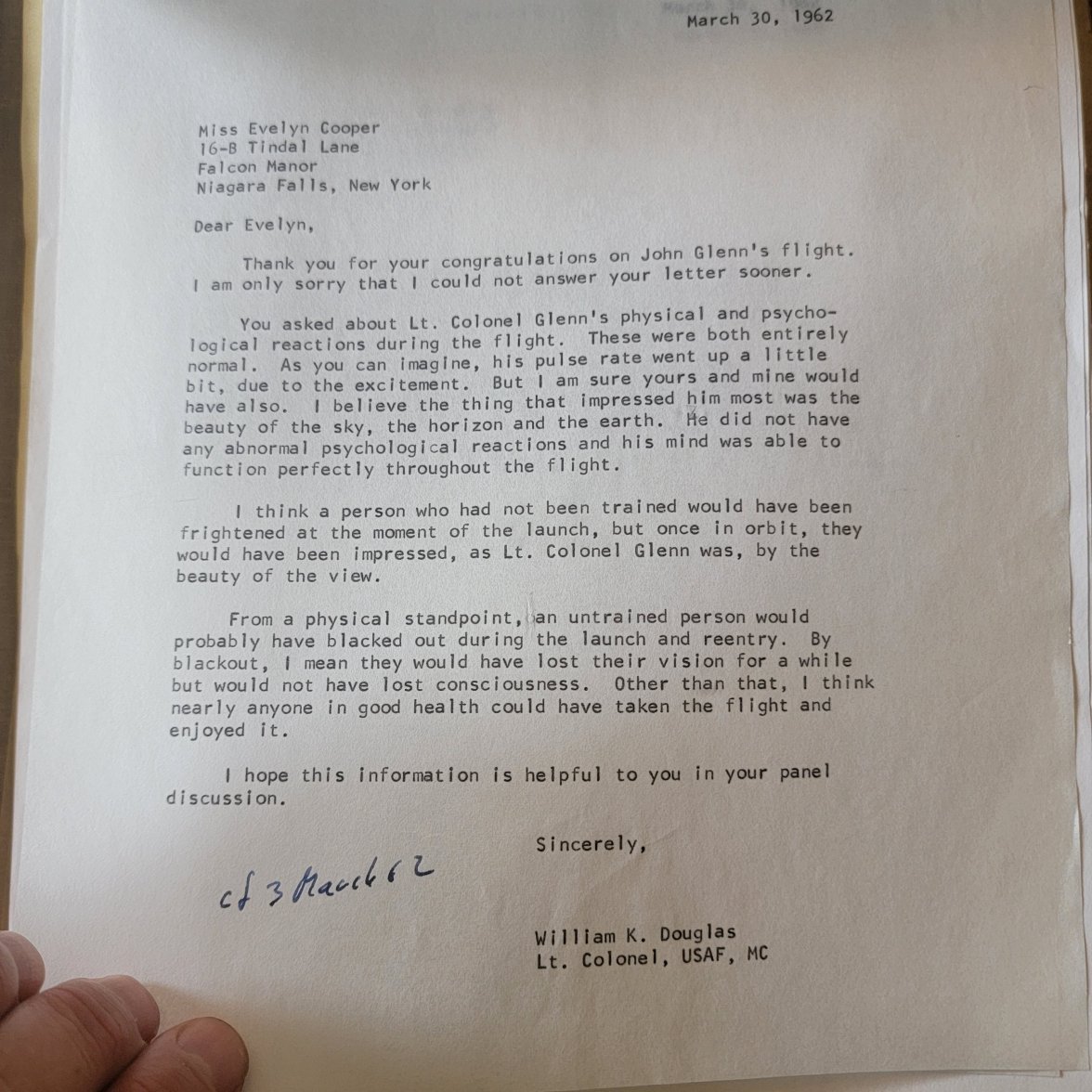

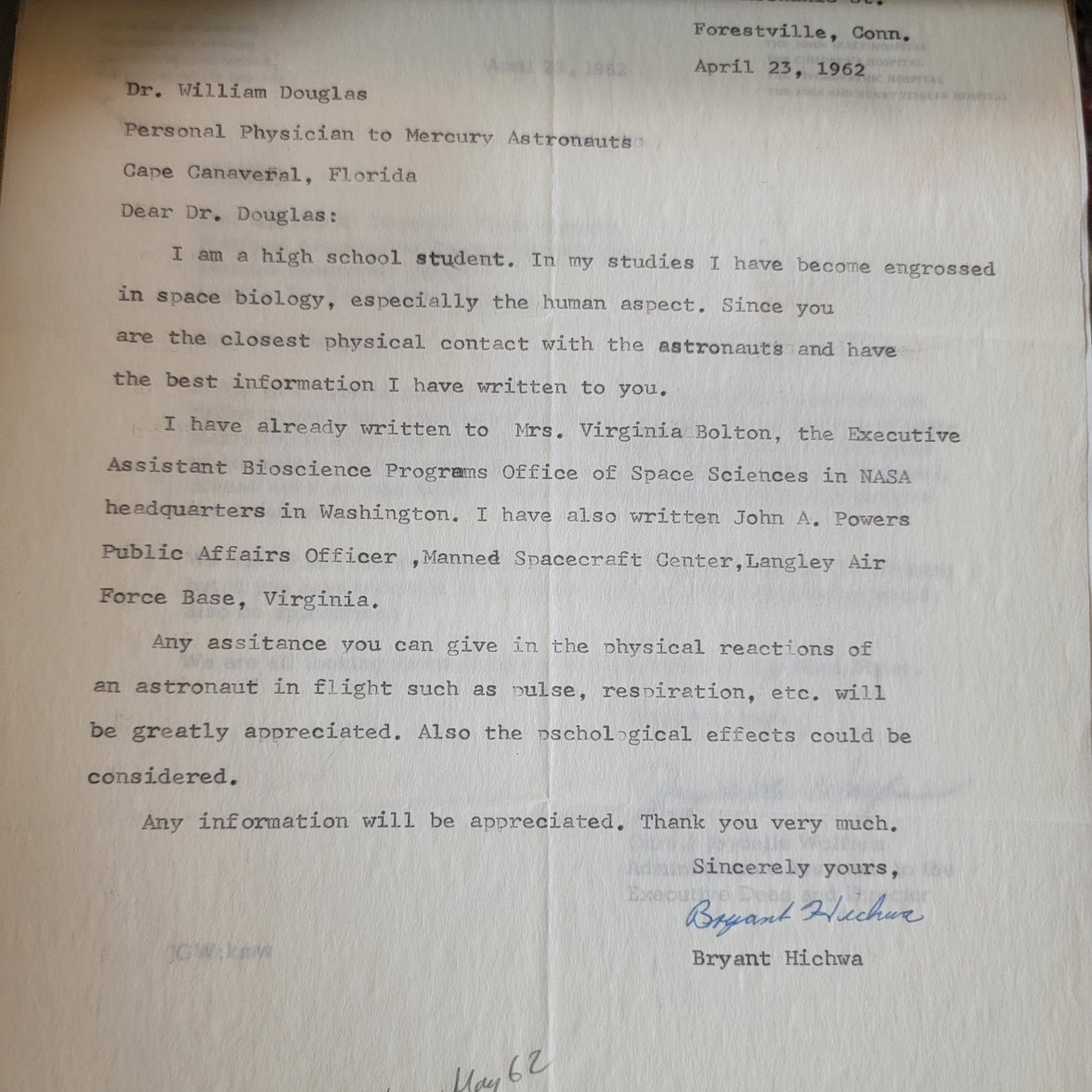

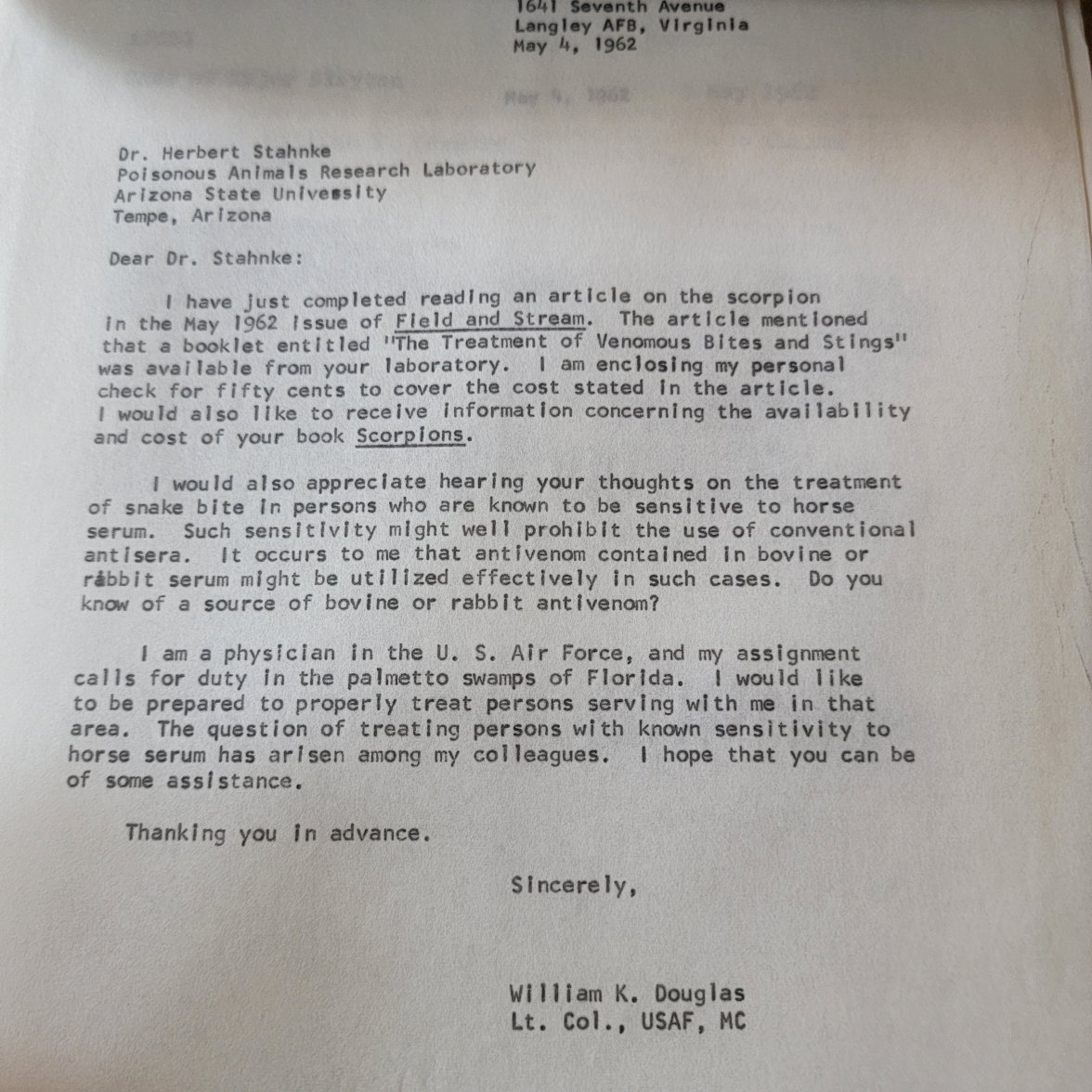

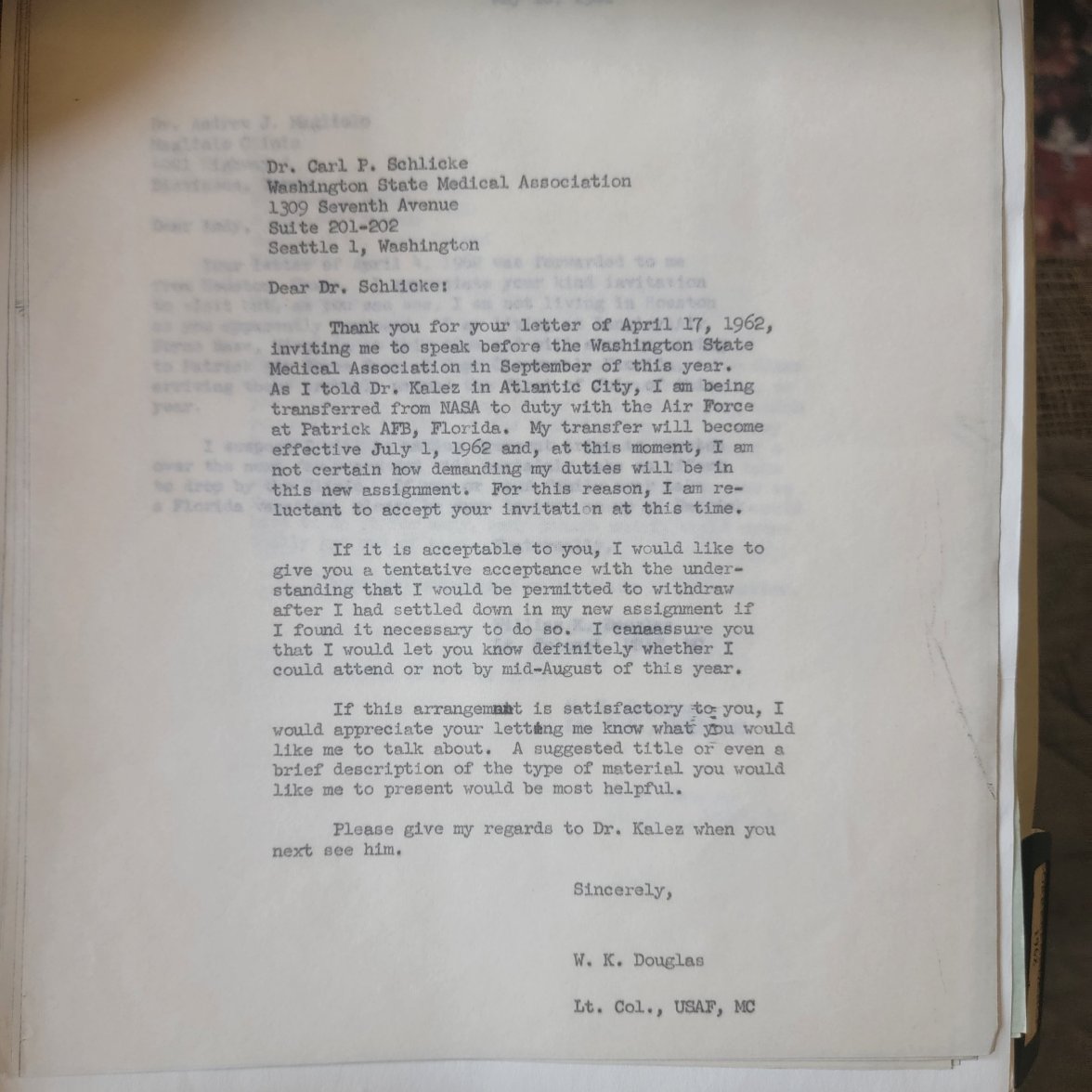

There are many other copies of correspondence Dr. Douglas had with school kids and ordinary citizens requesting autographs, as well as dozens of institutions requesting he speak at an engagement. He was clearly a very busy man in an uncharted new field of humans operating in space. Yet he not only kept each letter, he answered each one politely and respectfully. Dr. Douglas was a great representative of the program.

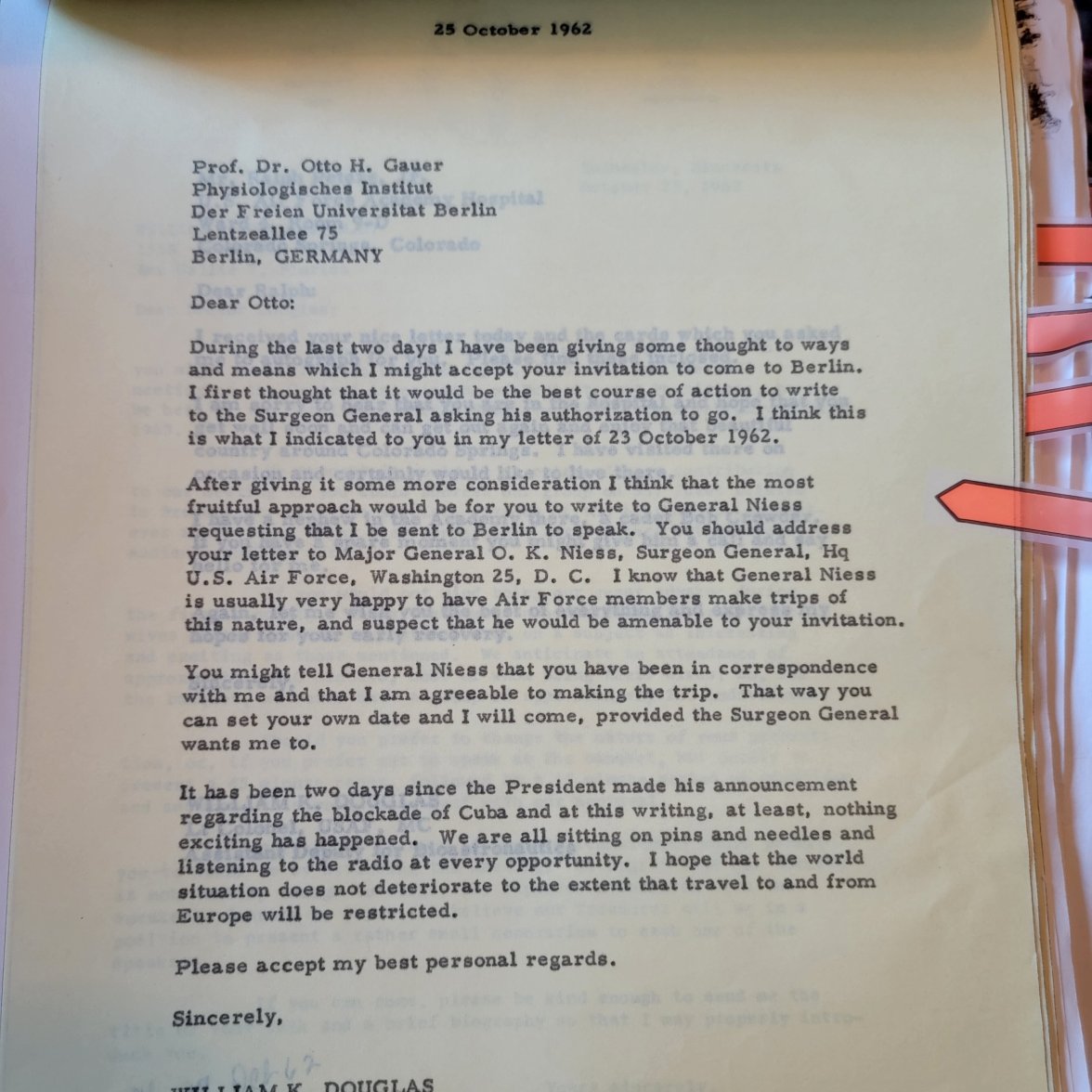

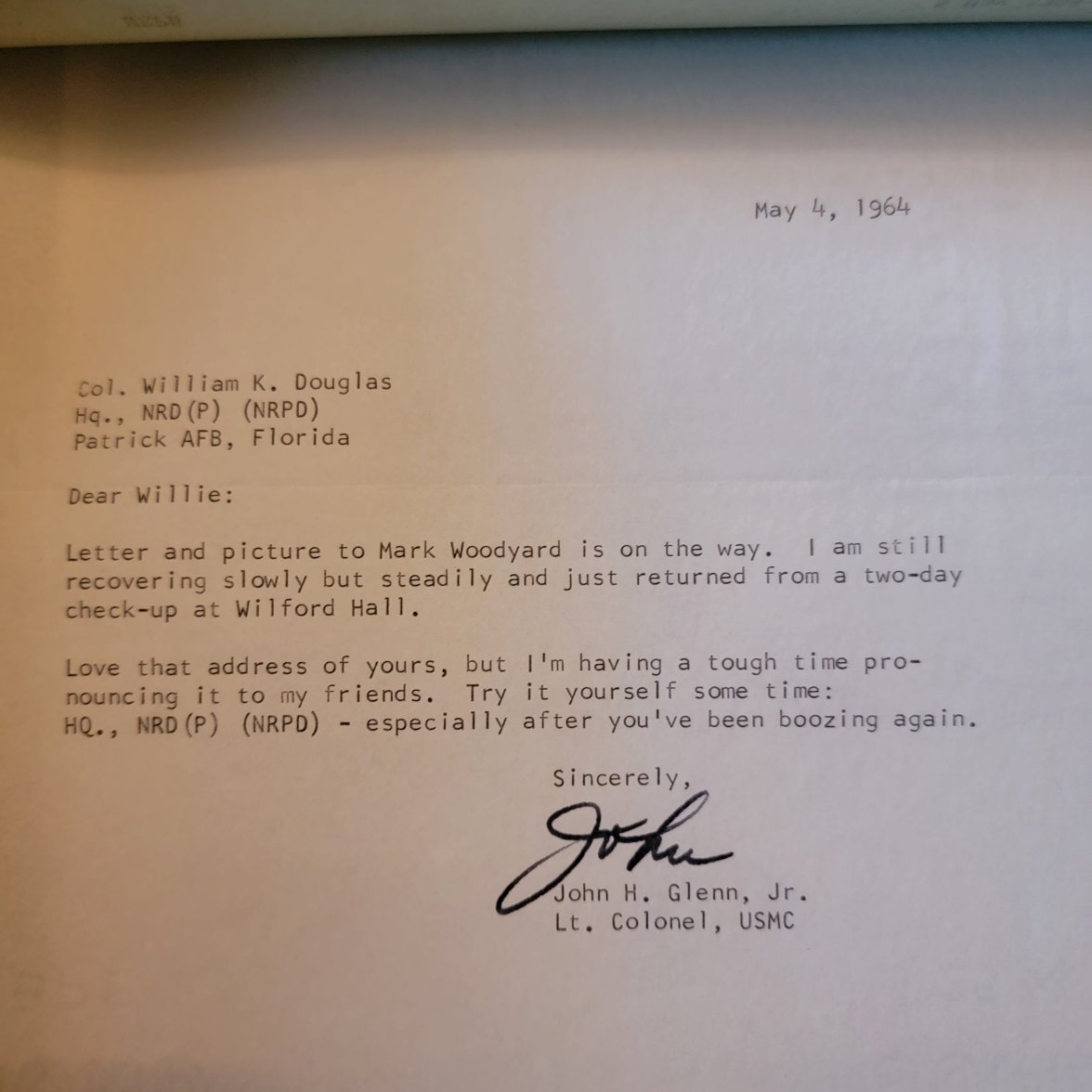

There are other interesting letters that I would like to share. They won't be as long. This post was long because it seemed the best way to share the overall sense of what comes across in reading the collected documents.

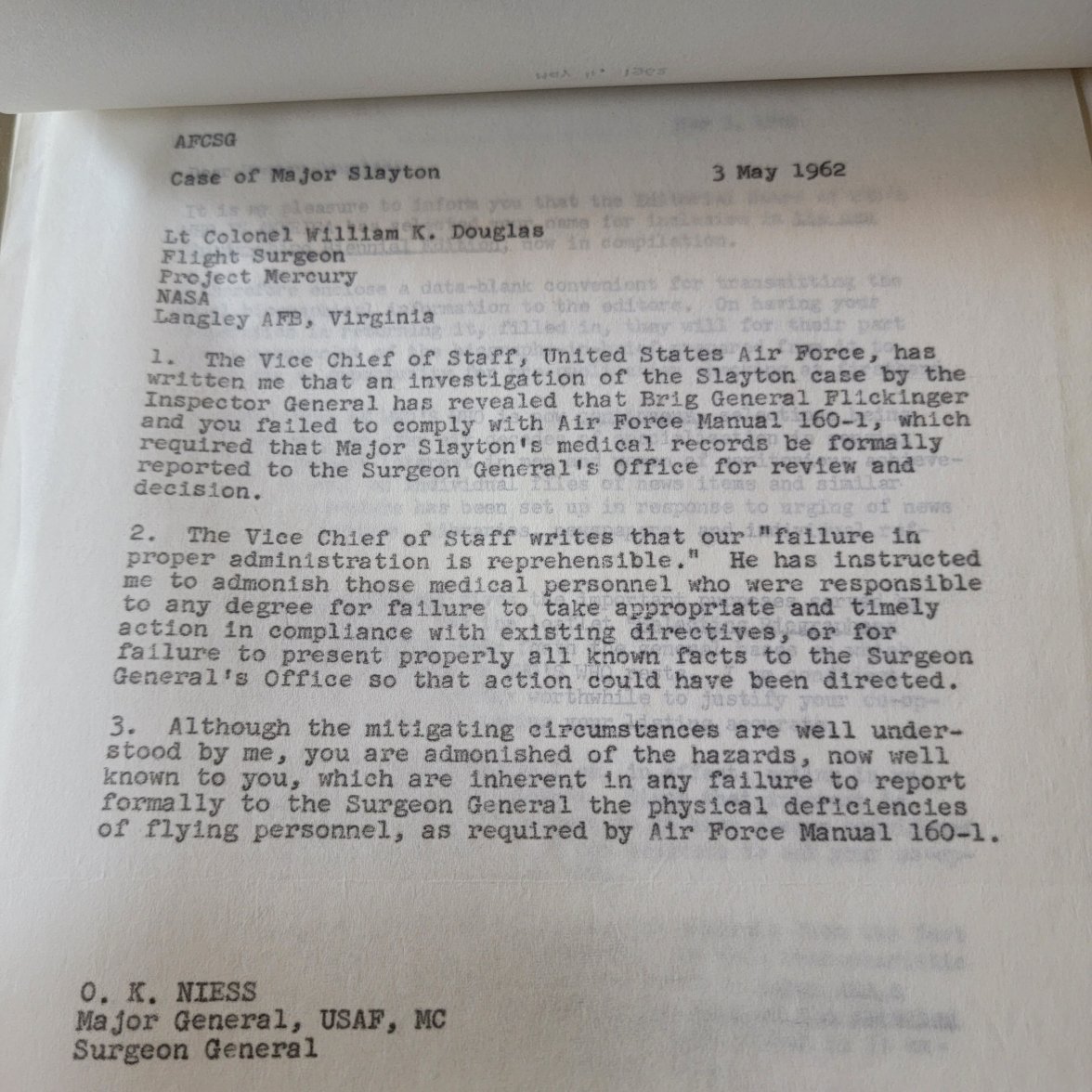

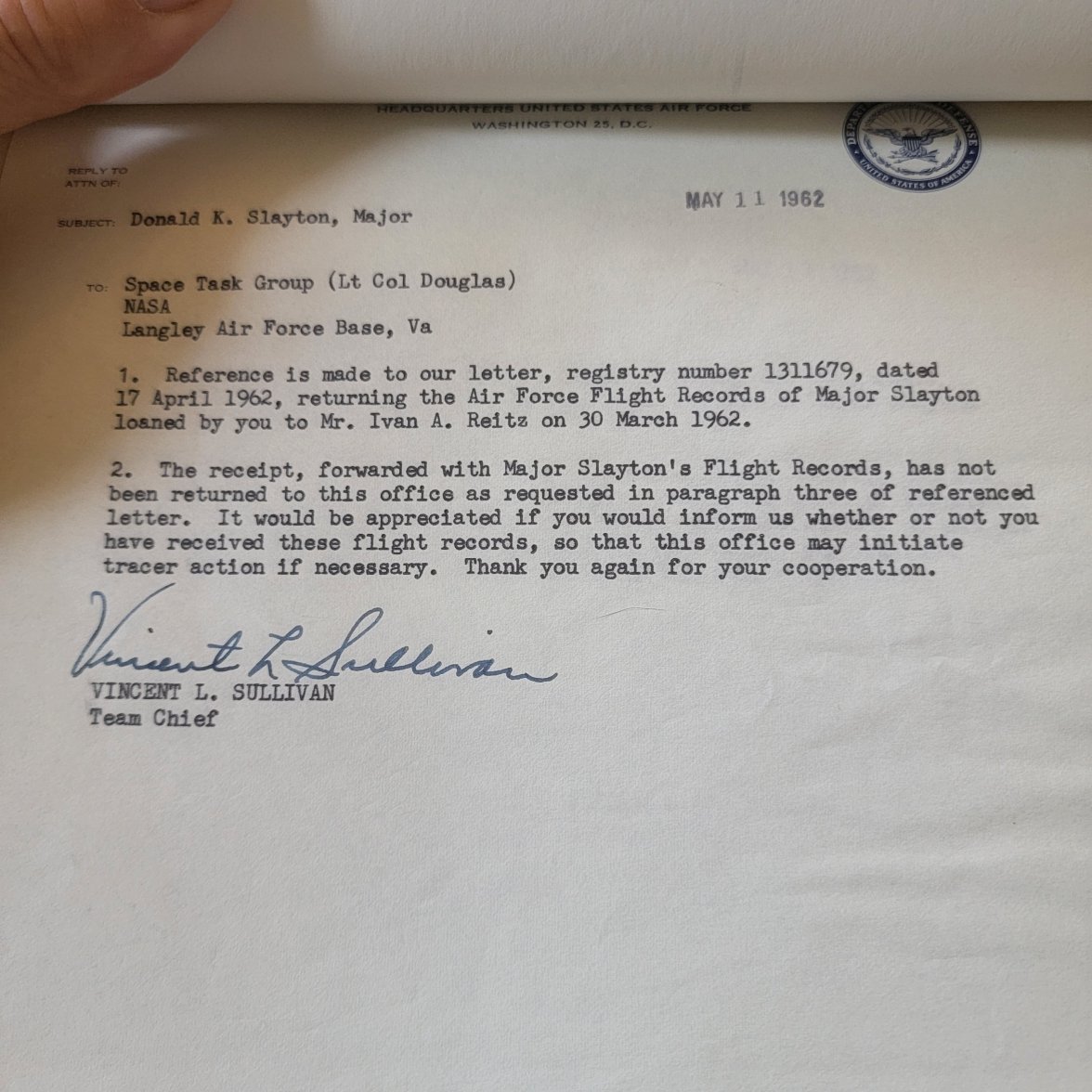

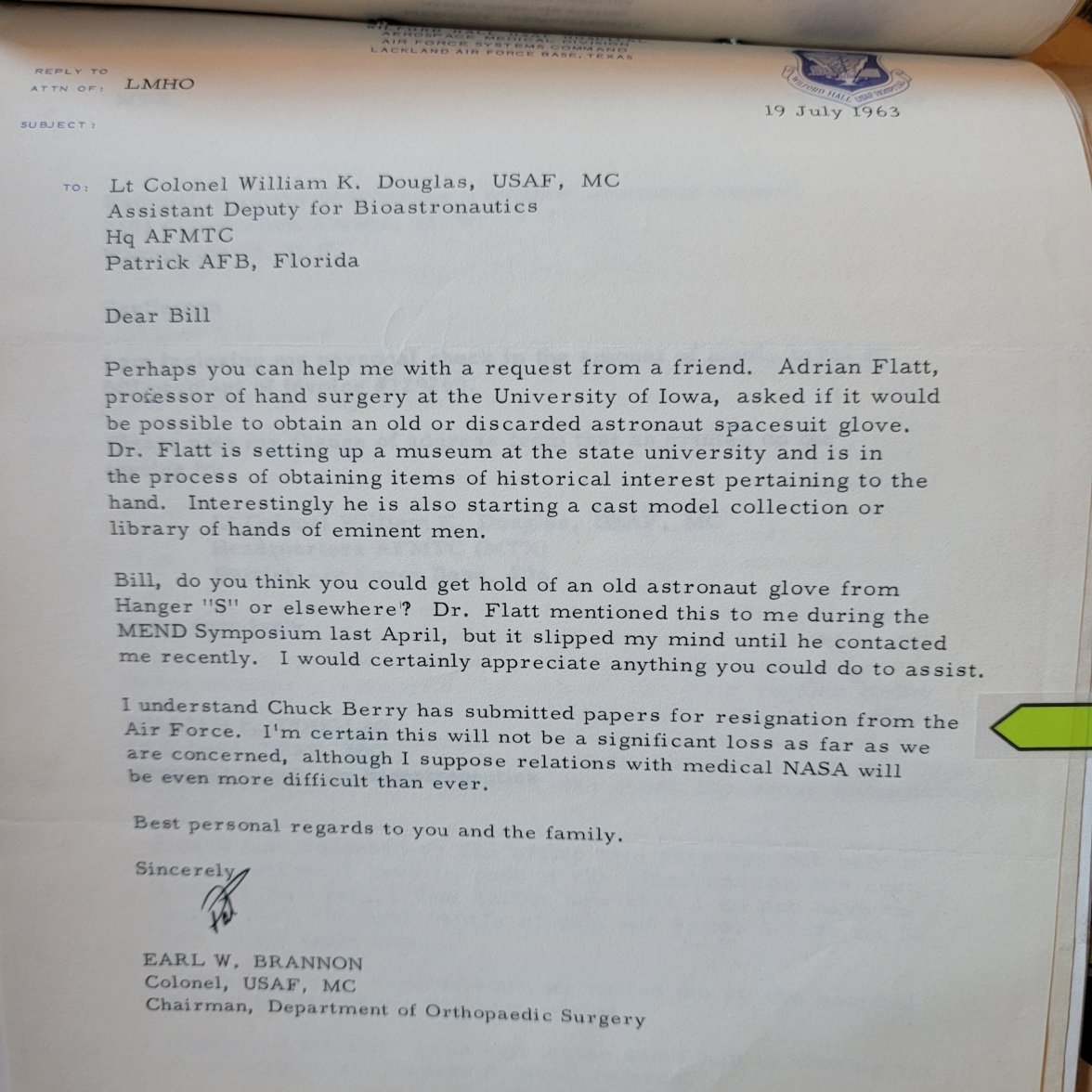

Edit: this letter dated 19 July, 1963 to Dr. Douglas states: "I understand Chuck Berry has submitted papers for resignation from the Air Force. I'm certain this will not be a significant loss as far as we are concerned, although I suppose relations with medical NASA will be even more difficult than ever."

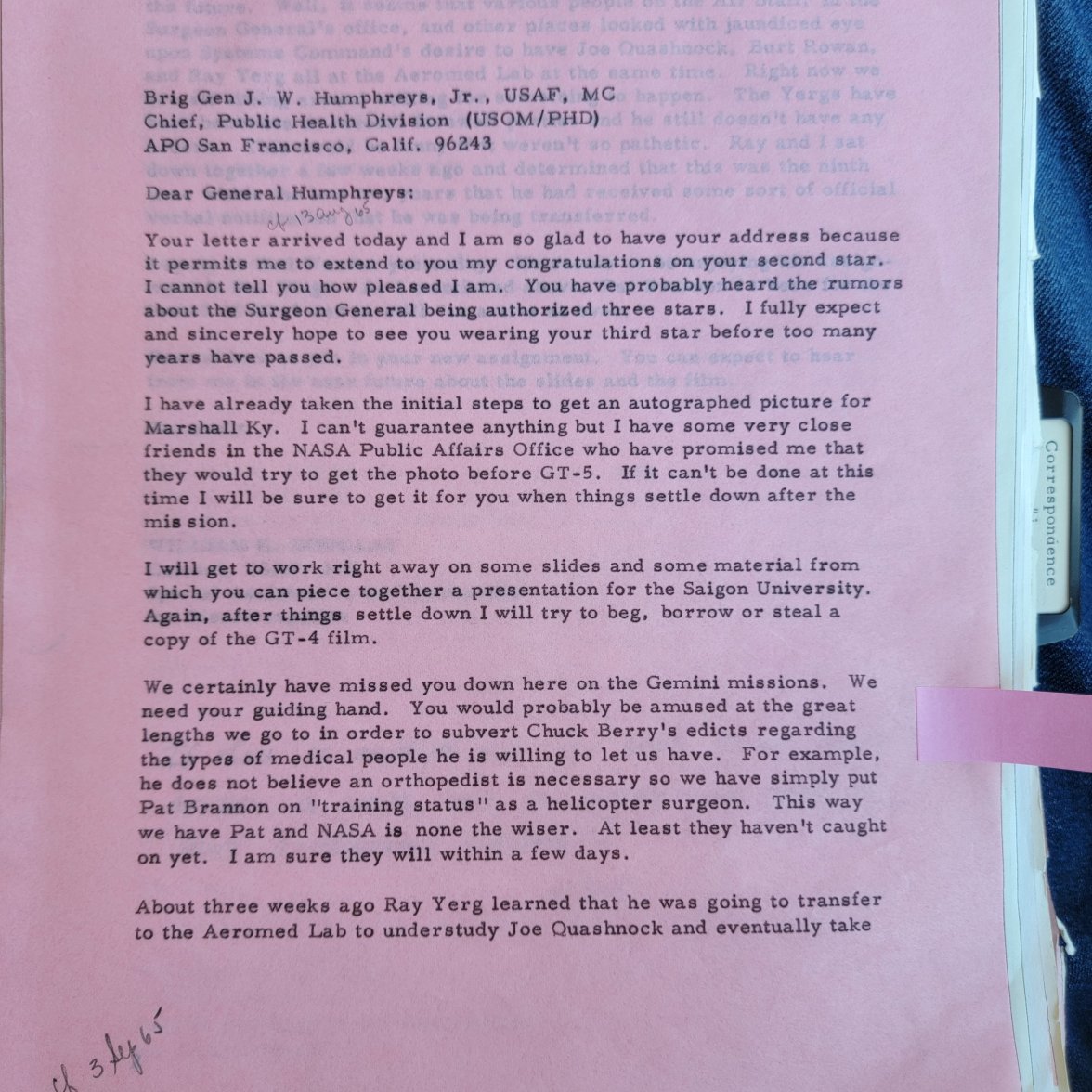

Edit: Another letter about Chuck Berry:

"We need your guiding hand. You would probably be amused at the great lengths we go in order to subvert Chuck Berry's edicts regarding the types of medical people he is willing to let us have. For example, he does not believe an orthopedist is necessary so we have simply put Pat Brannon on 'training status' as a helicopter surgeon. This way we have Pat and NASA is none the wiser. At least they haven't caught on yet. I am sure they will within a few days."