oddboy

·Hey gang,

This came across my stream this morning and I thought there might be a few here who would get a kick out of it....

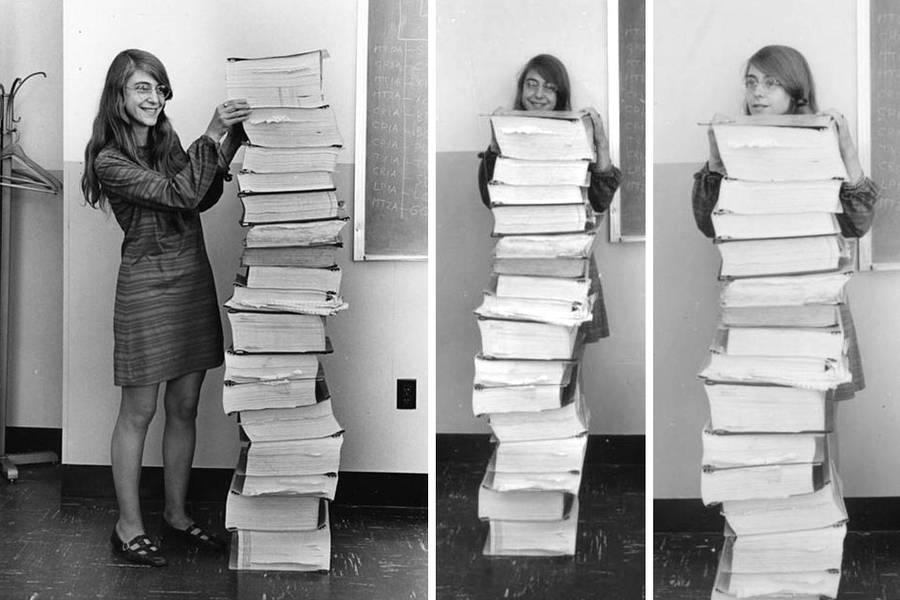

The Code that took Astronauts to the Moon is full of Comedy and Heroism

I've seen some pretty funny code/comments too, but I think some of these are just perfect.

This came across my stream this morning and I thought there might be a few here who would get a kick out of it....

The Code that took Astronauts to the Moon is full of Comedy and Heroism

I've seen some pretty funny code/comments too, but I think some of these are just perfect.