pdxleaf

·https://wapo.st/436sLlr

May 20, 2025 at 10:41 p.m. EDTYesterday at 10:41 p.m. EDT

By Emily Langer

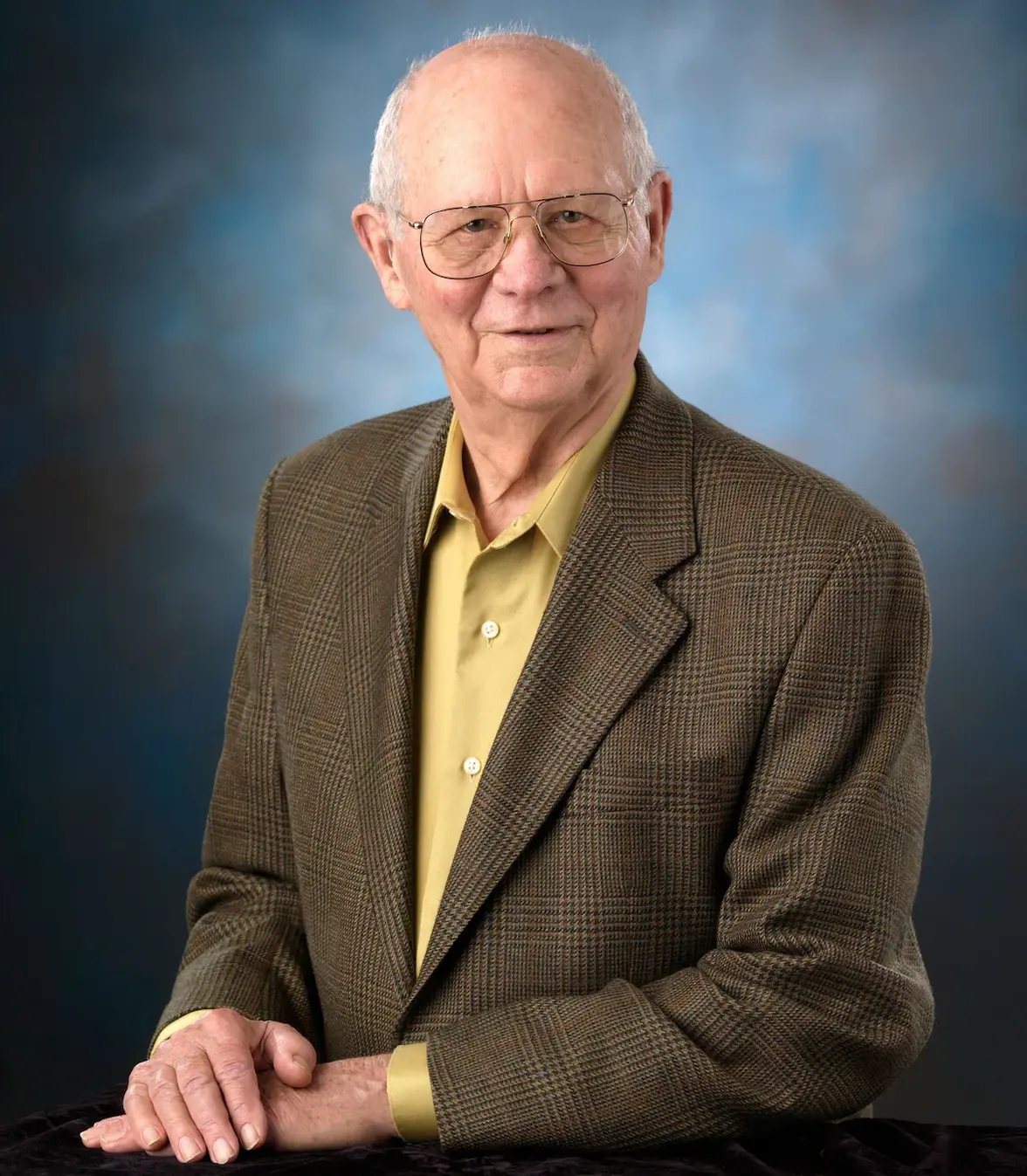

Ed Smylie, who became a quiet hero of the space age in 1970 when he and his fellow NASA engineers jury-rigged an air filter that kept the three Apollo 13 astronauts alive after an onboard explosion sent them hurtling back to Earth, died April 21 at a hospice facility in Crossville, Tennessee. He was 95.

He had complications from dementia, said his son, Steve Smylie.

Mr. Smylie was working for the Douglas Aircraft Co. in 1961 when President John F. Kennedy set a goal of “landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to the Earth.” Mr. Smylie, who was trained as a mechanical engineer, said that he decided then and there that he “wanted to be a part” of that mission.

Rallying Americans to his audacious aim, Kennedy memorably declared that “we choose to go to the moon in this decade and do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard.” But Mr. Smylie could little have imagined, when he was hired by NASA in 1962 and tasked with developing spacesuits and life support systems for astronauts, the gravity of the challenge he would face during the Apollo 13 mission.

Apollo 13, a drama that riveted the world at the time and became familiar to later generations through a blockbuster 1995 movie directed by Ron Howard, launched from Kennedy Space Center in Florida on April 11, 1970. The crew, Commander James A. Lovell Jr., command module pilot John L. “Jack” Swigert and lunar module pilot Fred Haise, was to be the third team of Apollo astronauts to achieve a moon landing.

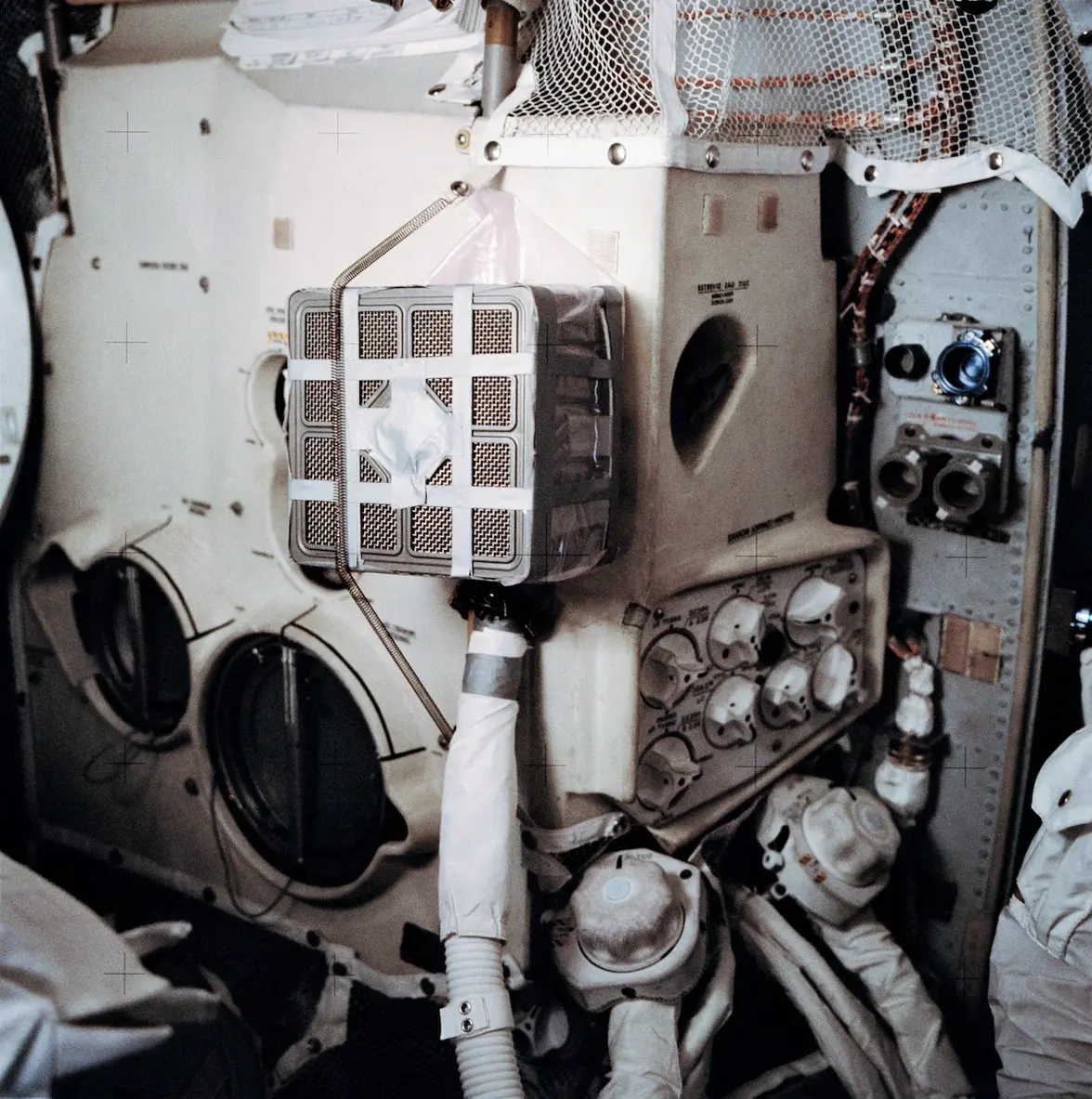

Two days in, the mission went terribly awry when an oxygen tank exploded, damaging the command module and forcing the crew to seek refuge in the lunar module — which was no longer fated to touch the moon. There was enough oxygen to keep the three astronauts alive for the return trip to Earth. But the lunar module’s existing equipment was designed to filter the carbon dioxide exhaled by only two. Without greater capacity for air filtration, the crew would not make it back alive.

Years later, Mr. Smylie told the Associated Press that he was at home watching TV when he learned of the emergency and rushed to his post at the Manned Spacecraft Center in Houston.

“He immediately went to work trying to figure out a way they could come up with something that would solve the problem,” Jerry Bostick, the mission’s flight dynamics officer, recalled in an interview.

Mr. Smylie and his team were confronted with a vexing problem. The command module was stocked with lithium hydroxide canisters to filter carbon dioxide. But they were box-shaped. The lunar module required cylindrical filters.

“You can’t put a square peg in a round hole,” Mr. Smylie later recalled, citing the old aphorism, “and that’s what we had.”

He and dozens of colleagues set about proving the aphorism wrong. Using only supplies on the crew’s stowage list — materials including plastic bags, spacesuit hoses and that ever useful fix-it supply, duct tape — they fashioned a working system.

“I felt like we were home free,” Mr. Smylie later remarked. “One thing a Southern boy will never say is, ‘I don’t think duct tape will fix it.’”

NASA radioed instructions to the astronauts, who replicated the design in space. Stripped of the life-or-death consequences at stake, the transcript reads like instructions for a DIY project:

“We want you to take the tape and cut out two pieces about three feet long, or a good arm’s length, and what you’re — what we want you to do with them is to make two belts around the sides of the canister, one belt near the top and one belt near the bottom, with the sticky side out; wrap it around, sticky side out, as tight as possible. It’ll probably take both of you to get it nice and snug. Over.”

In about an hour, according to the Smithsonian Institution’s National Air and Space Museum, the device was working. Dangers remained for the astronauts — the spaceship had to hit the atmosphere at just the right angle as it returned to Earth — but on April 17 they safely splashed into the South Pacific.

The movie “Apollo 13,” which starred Tom Hanks as Lovell, Kevin Bacon as Swigert and Bill Paxton as Haise, took minor poetic license with the events it depicted. It popularized a phrase — “Houston, we have a problem” — that the astronauts did not in fact utter when the oxygen tank exploded. (Swigert radioed to the command center, “Okay, Houston, we’ve had a problem here,” before Lovell added, “Uh, Houston, we’ve had a problem.”)

But the movie accurately reflected the

enterprising spirit of the engineers who worked to bring the astronauts home. Awarding the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian honor, to the Apollo 13 mission operations team, President Richard M. Nixon made special mention of Mr. Smylie, who was head of the crew systems division, and his deputy, James V. Correale.

“They are men whose names simply represent the whole team,” Nixon said. “And they had a jerry-built operation which worked, and had that not occurred, these men would not have gotten back.”

Mr. Smylie sought to deflect attention, however, remarking in a NASA oral history of the device that saved the astronauts’ lives, “a mechanical engineering sophomore in college could have come up with it.” He shared any praise with his colleagues for their collective “15 minutes of fame.”

Robert Edwin Smylie, one of two sons, was born on his maternal grandfather’s farm in Lincoln County, Mississippi, on Dec. 25, 1929. His father delivered ice in the days of ice boxes and later, after the advent of refrigerators, ran an ice-making facility. His mother managed the home.

Mr. Smylie received a bachelor’s degree in mechanical engineering from what was then Mississippi State College (now Mississippi State University) in 1952, served in the Navy and then continued his studies at MSU, receiving a master’s degree. He worked for Douglas Aircraft on the DC-8 jet plane before joining NASA.

Mr. Smylie started on the job at NASA days before John Glenn became the first American to orbit Earth on Feb. 20, 1962. In 1969, Neil Armstrong, the commander of Apollo 11, became the first human to walk on the moon. Mr. Smylie took part in the Mercury, Apollo, Gemini, Skylab, Apollo-Soyuz and space shuttle programs.

“Every mission was a deep focus,” he said years later in an interview with MSU. “You couldn’t let your guard down. You couldn’t allow a mistake to happen.”

In the latter part of his career, Mr. Smylie worked in top roles at NASA headquarters in Washington and at the Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. After his retirement from NASA in 1983, he held executive positions with RCA, the Mitre Corp. and what was then the Grumman Corp.

Mr. Smylie’s marriage to June Reeves ended in divorce. His second wife, the former Carolyn Hall, died in 2024 after 41 years of marriage. Besides his son, survivors include two other children from his first marriage, Susan Smylie and Lisa Willis; two stepchildren, Natalie Hall and Andrew Hall; 12 grandchildren; and 15 great-grandchildren.

During his time at the Manned Spacecraft Center, Mr. Smylie and his family lived in the Houston suburb of El Lago, a few doors down from Haise and a few more houses down from Armstrong. Steve Smylie played regularly with one of Haise’s sons, who was spirited off to the Smylie home when reporters descended on the neighborhood amid Apollo 13’s harrowing journey in space.

Although they were neighbors and met on occasion, Mr. Smylie and Haise were too consumed by their separate roles in the space program for diversions such as cookouts and block parties. In a sense, by helping bring Haise and the other astronauts home, Mr. Smylie was not unlike a parachute rigger, packing chutes for paratroopers he did not intimately know.

“It’s very straightforward,” Haise, now 91, said in an interview. “If he and his people had not worked and figured out how to make [the filter] work, we would have died.”

Ed Smylie, engineer who helped save Apollo 13 crew, dies at 95

He and his NASA colleagues were credited with jury-rigging a carbon dioxide filter that allowed the astronauts to breathe as they made their way back to Earth.May 20, 2025 at 10:41 p.m. EDTYesterday at 10:41 p.m. EDT

By Emily Langer

Ed Smylie, who became a quiet hero of the space age in 1970 when he and his fellow NASA engineers jury-rigged an air filter that kept the three Apollo 13 astronauts alive after an onboard explosion sent them hurtling back to Earth, died April 21 at a hospice facility in Crossville, Tennessee. He was 95.

He had complications from dementia, said his son, Steve Smylie.

Mr. Smylie was working for the Douglas Aircraft Co. in 1961 when President John F. Kennedy set a goal of “landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to the Earth.” Mr. Smylie, who was trained as a mechanical engineer, said that he decided then and there that he “wanted to be a part” of that mission.

Rallying Americans to his audacious aim, Kennedy memorably declared that “we choose to go to the moon in this decade and do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard.” But Mr. Smylie could little have imagined, when he was hired by NASA in 1962 and tasked with developing spacesuits and life support systems for astronauts, the gravity of the challenge he would face during the Apollo 13 mission.

Apollo 13, a drama that riveted the world at the time and became familiar to later generations through a blockbuster 1995 movie directed by Ron Howard, launched from Kennedy Space Center in Florida on April 11, 1970. The crew, Commander James A. Lovell Jr., command module pilot John L. “Jack” Swigert and lunar module pilot Fred Haise, was to be the third team of Apollo astronauts to achieve a moon landing.

Two days in, the mission went terribly awry when an oxygen tank exploded, damaging the command module and forcing the crew to seek refuge in the lunar module — which was no longer fated to touch the moon. There was enough oxygen to keep the three astronauts alive for the return trip to Earth. But the lunar module’s existing equipment was designed to filter the carbon dioxide exhaled by only two. Without greater capacity for air filtration, the crew would not make it back alive.

Years later, Mr. Smylie told the Associated Press that he was at home watching TV when he learned of the emergency and rushed to his post at the Manned Spacecraft Center in Houston.

“He immediately went to work trying to figure out a way they could come up with something that would solve the problem,” Jerry Bostick, the mission’s flight dynamics officer, recalled in an interview.

Mr. Smylie and his team were confronted with a vexing problem. The command module was stocked with lithium hydroxide canisters to filter carbon dioxide. But they were box-shaped. The lunar module required cylindrical filters.

“You can’t put a square peg in a round hole,” Mr. Smylie later recalled, citing the old aphorism, “and that’s what we had.”

He and dozens of colleagues set about proving the aphorism wrong. Using only supplies on the crew’s stowage list — materials including plastic bags, spacesuit hoses and that ever useful fix-it supply, duct tape — they fashioned a working system.

“I felt like we were home free,” Mr. Smylie later remarked. “One thing a Southern boy will never say is, ‘I don’t think duct tape will fix it.’”

NASA radioed instructions to the astronauts, who replicated the design in space. Stripped of the life-or-death consequences at stake, the transcript reads like instructions for a DIY project:

“We want you to take the tape and cut out two pieces about three feet long, or a good arm’s length, and what you’re — what we want you to do with them is to make two belts around the sides of the canister, one belt near the top and one belt near the bottom, with the sticky side out; wrap it around, sticky side out, as tight as possible. It’ll probably take both of you to get it nice and snug. Over.”

In about an hour, according to the Smithsonian Institution’s National Air and Space Museum, the device was working. Dangers remained for the astronauts — the spaceship had to hit the atmosphere at just the right angle as it returned to Earth — but on April 17 they safely splashed into the South Pacific.

The movie “Apollo 13,” which starred Tom Hanks as Lovell, Kevin Bacon as Swigert and Bill Paxton as Haise, took minor poetic license with the events it depicted. It popularized a phrase — “Houston, we have a problem” — that the astronauts did not in fact utter when the oxygen tank exploded. (Swigert radioed to the command center, “Okay, Houston, we’ve had a problem here,” before Lovell added, “Uh, Houston, we’ve had a problem.”)

But the movie accurately reflected the

enterprising spirit of the engineers who worked to bring the astronauts home. Awarding the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian honor, to the Apollo 13 mission operations team, President Richard M. Nixon made special mention of Mr. Smylie, who was head of the crew systems division, and his deputy, James V. Correale.

“They are men whose names simply represent the whole team,” Nixon said. “And they had a jerry-built operation which worked, and had that not occurred, these men would not have gotten back.”

Mr. Smylie sought to deflect attention, however, remarking in a NASA oral history of the device that saved the astronauts’ lives, “a mechanical engineering sophomore in college could have come up with it.” He shared any praise with his colleagues for their collective “15 minutes of fame.”

Robert Edwin Smylie, one of two sons, was born on his maternal grandfather’s farm in Lincoln County, Mississippi, on Dec. 25, 1929. His father delivered ice in the days of ice boxes and later, after the advent of refrigerators, ran an ice-making facility. His mother managed the home.

Mr. Smylie received a bachelor’s degree in mechanical engineering from what was then Mississippi State College (now Mississippi State University) in 1952, served in the Navy and then continued his studies at MSU, receiving a master’s degree. He worked for Douglas Aircraft on the DC-8 jet plane before joining NASA.

Mr. Smylie started on the job at NASA days before John Glenn became the first American to orbit Earth on Feb. 20, 1962. In 1969, Neil Armstrong, the commander of Apollo 11, became the first human to walk on the moon. Mr. Smylie took part in the Mercury, Apollo, Gemini, Skylab, Apollo-Soyuz and space shuttle programs.

“Every mission was a deep focus,” he said years later in an interview with MSU. “You couldn’t let your guard down. You couldn’t allow a mistake to happen.”

In the latter part of his career, Mr. Smylie worked in top roles at NASA headquarters in Washington and at the Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. After his retirement from NASA in 1983, he held executive positions with RCA, the Mitre Corp. and what was then the Grumman Corp.

Mr. Smylie’s marriage to June Reeves ended in divorce. His second wife, the former Carolyn Hall, died in 2024 after 41 years of marriage. Besides his son, survivors include two other children from his first marriage, Susan Smylie and Lisa Willis; two stepchildren, Natalie Hall and Andrew Hall; 12 grandchildren; and 15 great-grandchildren.

During his time at the Manned Spacecraft Center, Mr. Smylie and his family lived in the Houston suburb of El Lago, a few doors down from Haise and a few more houses down from Armstrong. Steve Smylie played regularly with one of Haise’s sons, who was spirited off to the Smylie home when reporters descended on the neighborhood amid Apollo 13’s harrowing journey in space.

Although they were neighbors and met on occasion, Mr. Smylie and Haise were too consumed by their separate roles in the space program for diversions such as cookouts and block parties. In a sense, by helping bring Haise and the other astronauts home, Mr. Smylie was not unlike a parachute rigger, packing chutes for paratroopers he did not intimately know.

“It’s very straightforward,” Haise, now 91, said in an interview. “If he and his people had not worked and figured out how to make [the filter] work, we would have died.”

Edited: